There are many showrunners in contemporary Hollywood who are, essentially, all-powerful – Vince Gilligan and Aaron Sorkin have been able to do what they like for a considerable time now, for instance, and I doubt anyone’s giving the White Lotus’s Mike White too many notes, unless they’re blank checks – but there are two men who are primus inter pares when it comes to their relationship with their studios. Ryan Murphy more or less is Mr. Netflix, as can be seen by the streaming service merrily bankrolling everything he writes and/or creates – even something as unpleasant and morally corrupt as the recent Ed Gein show – and Taylor Sheridan and Paramount have been hand in glove for years now. Until, that is, they’re not.

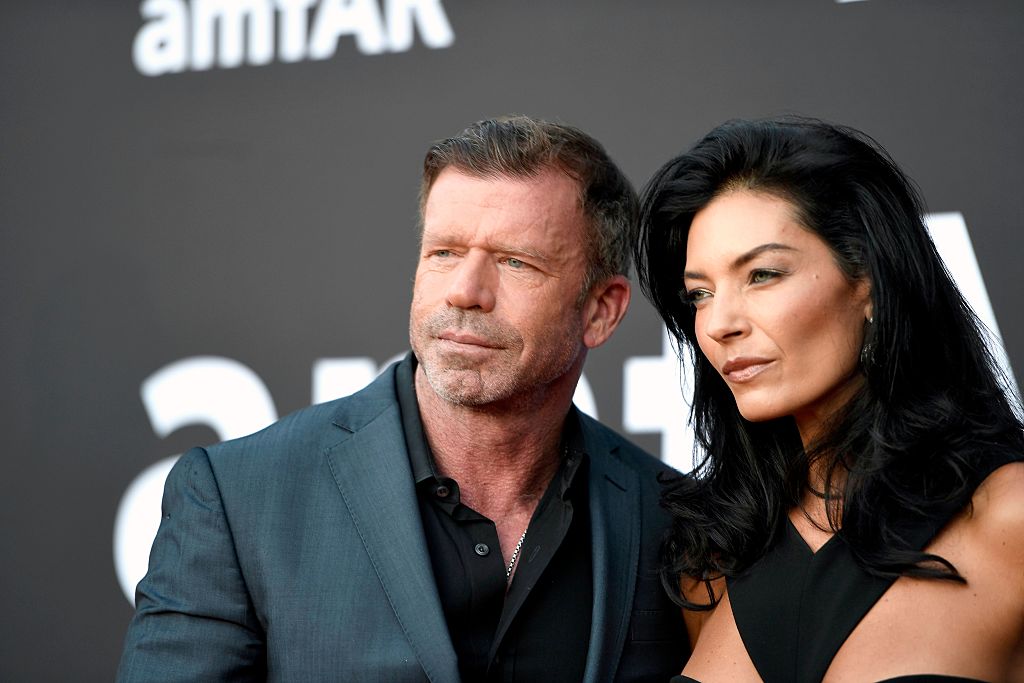

The reason why Taylor Sheridan is leaving the network with whom he has had huge success for years is, as usual, a dispute about money. His perspective is that his work with Paramount, during which time he has more or less reinvented the contemporary western with such shows as Yellowstone and Landman, as well as prequels including 1883 and 1923 and such popular crime series as Tulsa King and Mayor of Kingstown, has been exemplary both on an artistic and commercial level, and that he deserves a Murphy-level deal. Paramount’s argument, as expressed by its new CEO David Ellison, is that Sheridan may be a hugely talented writer-director-showrunner, but he is ultimately an expendable figure who has, wrongly, seen himself as bigger than the shows he has produced.

Both sides have ground for their respective arguments. When Yellowstone was at its peak, it managed to be one of those rare shows that overcame the potential hokiness of its premise (and some terrible early reviews) to become appointment viewing, the Dynasty for our time but considerably better. And everything that Sheridan has worked on since has been similarly successful, even if the spy thriller show Lioness has never really caught fire, despite a starry cast including Morgan Freeman, Nicole Kidman and Zoe Saldaña. In an America that is now considerably more attuned to MAGA sensibilities that it was when he began his screenwriting career a decade ago with the (excellent) films Sicario and Hell or High Water, Sheridan can convincingly suggest that he has captured the zeitgeist of his country more entertainingly than any other writer today, and that this success should be rewarded accordingly.

Ellison, however, is said to be less enamored of Sheridan’s considerable ego. When it was suggested to the showrunner that he produce a show celebrating America’s 250th anniversary, he simply refused, suggesting that it was “too politically charged”. Sheridan, however, was smarting from Paramount’s refusal to make one of his screenplays, entitled Capture the Flag – no prizes for guessing what kind of genre of film that would have been – and seemingly decided that the studio that had built his career was no longer the right fit for him. Enter Donna Langley, all-powerful head of Universal, and a woman with considerable form in luring away talent from their former homes: it was she who convinced Christopher Nolan to leave Warner Bros and won him Oscars for Oppenheimer in the process. Sheridan’s price, paid willingly: a billion-dollar deal and complete creative control.

There are, of course, several more shows left to run in his Paramount deal, which does not expire until 2028, but it looks unlikely that such series as the Yellowstone spin-offs 1944 and The Madison will be entered into with the same zeal that his previous work. Certainly, Sheridan has been working at a rate of energy that would kill many lesser men, and it has been whispered that Ellison believed that not only was the hyphenate at risk of creative burn-out, but that with him gone, it would be easier to control Paramount, rather than with this particular alpha male attempting to dominate proceedings.

He may, of course, be right. Yet if there’s anything Sheridan has done successfully in his shows, it is to bring in the big dog that so many of his peers have shied away from creating, and make him not just relatable, but likable. It is not too big a stretch to believe that many of these figures were created in his own image, and that Sheridan himself is as outsized and swashbuckling as any John Dutton or Mike McLusky. What are the chances that a future show of his will feature a similarly titanic lead taking on the callow entertainment industry, and winning in the process? Sheridan – and Universal – will be hoping that life imitates art, and vice versa. Ellison will be just as fervently hoping the opposite, and the rest of us will be watching with as much fascination as we have devoted to the shows.

Leave a Reply