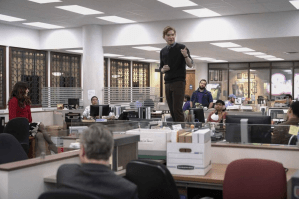

Last month, chess grandmaster Daniel “Danya” Naroditsky started streaming again from his house in North Carolina. He had taken a break from it recently; I was one of at least a thousand viewers to welcome him back that night. But something was off. Danya, normally effusive and energetic, seemed haggard. As the broadcast went on, he began to slur his words. At one point, realizing he’d made a wrong move, he punched himself in the head. It was painful to watch.

Throughout, Danya talked about a man whose accusations had allegedly subjected him to torment and abuse over the past year. At times, he was close to tears. As the stream went on, Danya became increasingly vacant, whispering in Russian, his mother tongue, as he recalled the pain of seeing sane, well-meaning people undermine his experience, due to allegations that had made his life hell. He began to slouch in his chair, drifting in and out of consciousness.

When Danya eventually stopped streaming, a man called Vladimir Kramnik, a former chess world champion, posted a string of messages to his 24,000 followers on X, speculating Danya was on drugs. He posted an image with the words, “Don’t do drugs.” Kramnik is the man who had made the allegations that Danya had accused of ruining his life. For the past year, Kramnik had been publicly claiming Danya should be investigated for cheating in online chess. Then, on Sunday October 19, Danya was found dead. He was 29.

The chess world convulsed. Danya wasn’t just an exceptional player – he won the US blitz championship last year – he was a gifted teacher and could explain complex chess tactics as if he were describing the most beautiful thing in the world. Players and creators released videos of themselves in floods of tears. But the emotion was also a sign of growing unease within the game and its legions of fans; a feeling that the chess’s post-Covid success has morphed into something ugly and out of control.

Streaming has changed the game beyond recognition. The website chess.com now has more than 200 million members. Before its rise, aided by the pandemic, FIDE – chess’s century-old governing body – controlled almost every aspect of the game. The freely accessible, on-demand nature of chess.com’s broadcasts has created a new empire. Players now earn a fortune by streaming on Twitch, YouTube and through sponsorships – unthinkable just five years ago. But lockdown was the real turning point: boredom, The Queen’s Gambit and a melodramatic cast of social outcasts fused into an ecosystem that brought in millions of new fans.

Danya had been a central figure in this post-lockdown boom. He was born in San Mateo, California, in 1995, to a Jewish Soviet family. He studied history at Stanford and published his first book, Mastering Positional Chess, at the age of 14. At the time of his death, Danya had 490,000 subscribers.

Danya was seen as a truly good guy in a world that is increasingly populated by big egos. The game’s cast is operatic. Hikaru Nakamura, world number two and chess’s biggest streamer, is hugely gifted, brash and incredibly self-satisfied. Then there’s Magnus Carlsen, arguably the greatest player of all time, who made headlines this summer for throwing away a lead and punching the table. Hans Niemann is the enfant terrible of modern chess: arrogant, brilliant and permanently aggrieved.

The reaction to Danya’s death quickly curdled from grief into a row over who or what was to blame. Some seemed to hold Kramnik responsible – although Kramnik himself has strongly denied that he accused Danya of cheating and said Danya’s death was not his fault. Kramnik blamed something called “the chess mafia,” a spurious cabal made up of people at the top of the chess hierarchy. Kramnik implied that Danya might have been assassinated by this cabal. He didn’t give a reason why.

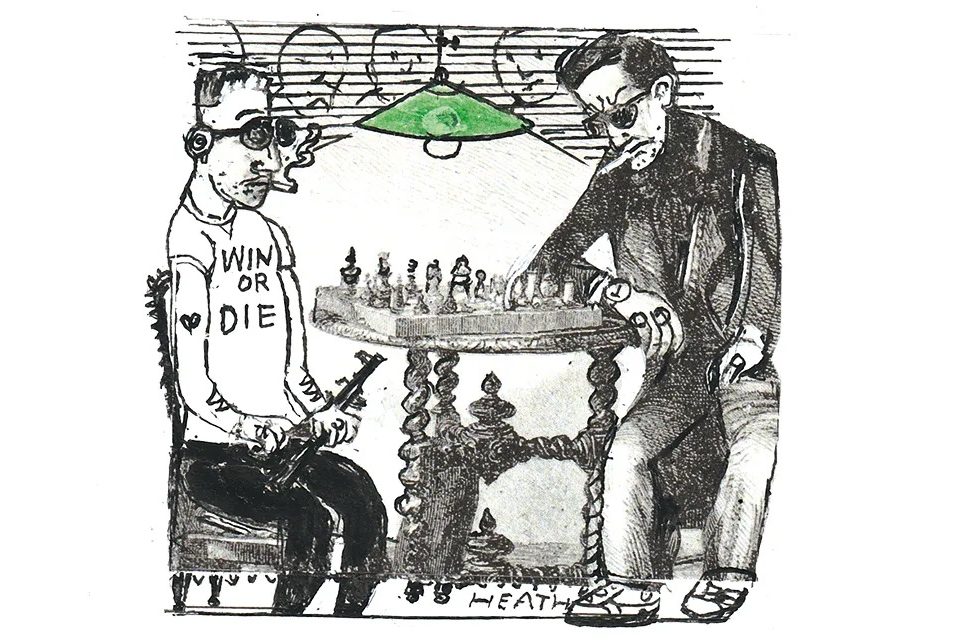

But ignore the claims and counterclaims: the fundamental issue at the heart of this tragedy is cheating – or, more accurately, the idea of cheating. It’s easy to cheat at chess. All you need is an internet connection.

Kramnik, once a titan of the chess world, spent the past year going down a rabbit hole of investigation and accusation. To Kramnik, chess streamers such as Danya should be investigated in case they were cheating in order to raise their rating, gaining prestige and winning money in online tournaments. He began compiling data on players he believed were playing above their natural skill level. Danya was one of Kramnik’s prime suspects. Almost every grandmaster came out in support of Danya, condemning Kramnik’s evidence. But these kinds of allegations, even if they are condemned, take their toll in the chess world.

Danya started being harassed by anonymous social media accounts. He began to retreat from public view. In the week after his death, his mother shared a statement saying that her son’s reputation as an honest, passionate chess player was the most important thing to him. Kramnik says he never accused Danya of cheating and that there has been an “orchestrated PR campaign” against him since Danya’s death.

The new celebrity chess players have never really known how to handle fame. The 2023 world champion, Ding Liren, recently admitted that during the most high-pressure moments of his young career he couldn’t sleep for months and descended into “darkness.” Grandmaster David Navara has spoken about having suicidal thoughts after being accused of cheating by Kramnik. Niemann is a provocateur, but when Carlsen accused him of cheating more than he had admitted, he said it nearly ruined his life. The terrible tragedy for so many fans – for all the people whose relationship with the game was so intimately molded by Danya’s utter brilliance – is that it was the intensity of his passion that eventually seemed to kill him.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply