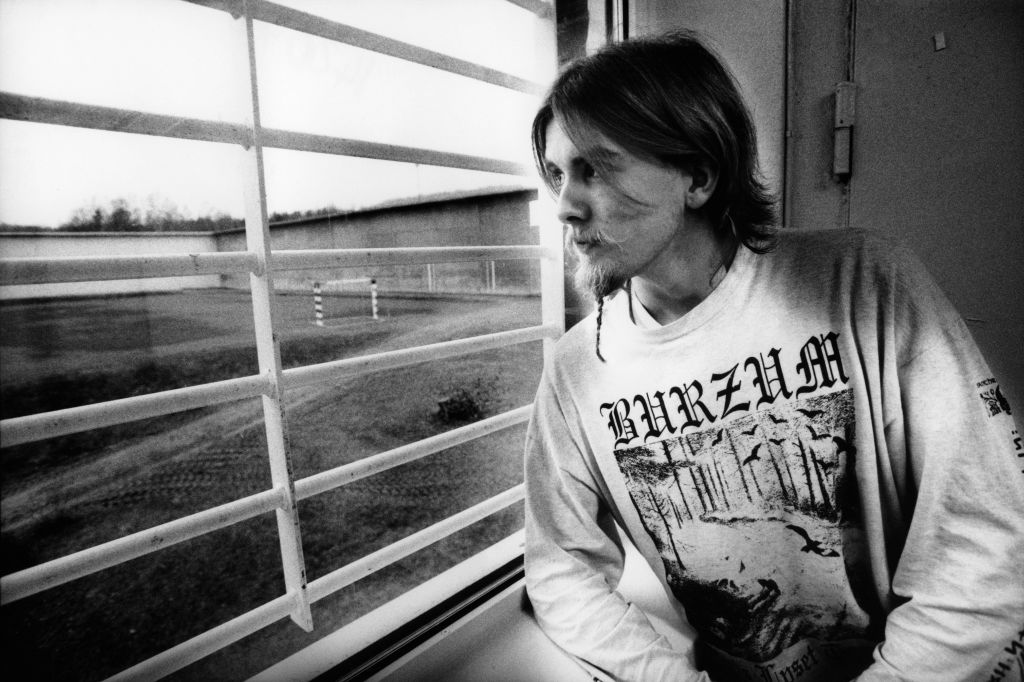

In his youth, Emil Lundin became obsessed with the idea of recording the world’s “most evil album.” The lanky, long-haired Swede formed a black-metal band and set to work.

He faced an immediate obstacle. In making history’s most nefarious musical creation, he could hardly use Swedish, with its singsong tones. English was also out of the question: he didn’t want to sound like ABBA. That left Latin, the native tongue of the occult and, it is said, of demons.

In a quest for suitably devilish lyrics, he pored over arcane texts. That led him to Latin editions of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers – badass early Christian monks – and St. Augustine’s Confessions. Before he knew it, he was sleeping on a concrete floor, rising in the night to pray and fasting until his cheekbones jutted out. Following his baptism by a Jesuit priest, he proclaimed the birth of a new musical form: Roman Catholic black metal (yet to be embraced by the Sistine Chapel choir).

Lundin’s conversion took place before the rise of artificial intelligence. If he was trying to create an infernal album today, you could imagine him turning to AI, with its god-like powers, in search of lyrical inspiration. Researchers tell us that seekers are engaging in AI-powered explorations of the occult, using specialized assistants such as Mistral Trismegistus-7B, which can churn out instructions on palm readings, rune casting and even flying a broomstick. Others are using AI tools to discover more about Christianity, asking platforms such as ChatGPT to interpret opaque Bible verses, write tailor-made prayers and offer guidance on moral dilemmas.

Amid this internet-enhanced spiritual ferment, with its “digital witches” and “tech Christians,” pews across the western world are filling with unexpected occupants: enthusiastic young people. According to a recent Bible Society study, they are portents of a “quiet revival” driven by Gen Z men and seen even in supposedly secular countries such as France and Finland.

Was Lundin’s conversion a precursor of this spiritual resurgence? Did it mark a shift within the black-metal scene – the start, perhaps, of an unquiet revival?

Dark and anarchic forms of music have long been a breeding ground for Christian converts. In heavy metal, there’s Iron Maiden drummer Nicko McBrain, who became a born-again Christian after a spiritual experience at a Florida church. Megadeth’s founder Dave Mustaine converted after stints in rehab. W.A.S.P. frontman Blackie Lawless used to wear a codpiece that shot out pyrotechnic sparks – and once malfunctioned on stage after cabin pressure had compressed the gunpowder on a transatlantic flight. Long after the burns had healed, he rediscovered his childhood faith.

Heavy metal gave way to extreme metal, which is similar but faster, angrier and more prone to growling than singing. Its many subgenres include thrash metal, death metal, doom metal and, of course, black metal.

Historians trace black metal back to a 1982 album of that name by Venom, who embraced satanic imagery with a theatrical flourish. The dark, aggressive sound caught on in the Nordic countries and, mysteriously, Switzerland. By the late 1980s, black metal had established its defining characteristics: anti-religious lyrics, shrieking vocals, fast guitars, relentless drumming, creepy atmospherics and lo-fi production. Frontmen wore “corpse paint” – make-up that made them look like month-old cadavers.

Any account of the subgenre must reckon with the lurid events of the early 1990s. They revolve around a much mythologized band called Mayhem. It was formed in Oslo in 1984. One of its first members, Kittil Kittilsen, had the good sense to get out early and later became a born-again Christian. In 1991, Mayhem’s vocalist, who went by the name of Dead, committed suicide. In 1992, bassist Varg Vikernes, also called Count Grishnackh, began burning churches, claiming he was exacting revenge for Christianity’s suppression of Norwegian pagan traditions. In 1993, Vikernes murdered Mayhem’s guitarist Euronymous.

At that stage, Mayhem still hadn’t released a full-length album. That came in 1994, with De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas (“Of the Mysteries of Lord Satan”), whose title track featured lyrics in pseudo-Latin. The cover depicted Trondheim’s ancient Nidaros Cathedral, prompting speculation that band members had intended to bomb the edifice on the album’s release date. Mayhem’s grim antics reenergized the black-metal scene, especially in the Nordic countries. But heavily sensationalized accounts of the band created a false impression that the subgenre is a teeming hotbed of criminality, rather than an uncompromisingly bleak artform favored by basement-dwelling teens.

As Mayhem’s fame spread, an Australian musician who recorded under the name Horde made an album inspired by the band’s raw sound. Hellig Usvart (“Holy Unblack”) contained a twist: its lyrics were vigorously Christian. On tracks such as “Crush the Bloodied Horns of the Goat,” Horde sang about eviscerating a symbolic representation of Satan.

The album scandalized black-metal fans and reputedly inspired death threats against its record label. Was this, as the Norwegian press suggested, a parody of Mayhem, or was it a sincere expression of Christian faith? The album’s creator came forward to explain that he wanted to shine a light into the “bleak, dark, hopeless, lifeless and negative void” of black metal. Horde had inadvertently created a new sub-subgenre, known as “unblack metal,” “white metal” or “Christian black metal,” often sonically indistinguishable from the original.

That was the background against which Emil Lundin underwent his conversion. In 2014, his band Reverorum ib Malacht released the album De Mysteriis Dom Christi (“Of the Mysteries of the Lord Christ”), in a pious nod to Mayhem. After he became Catholic, Lundin feared he might be killed by an aggrieved metalhead. In reality, he faced no backlash. This suggests that, despite its violent overtones, black metal may be more genuinely inclusive than many a liberal university campus.

Lundin came to see black metal as a form of Romanticism: a yearning for a pre-industrial world of mystery, drama and visceral emotion. The early 20th-century critic T.E. Hulme described Romanticism as “spilt religion.” Extreme metal, too, seems like a secular expression of religious instincts. Its anti-religious forms are ironically dependent on Christianity, a primary source of potent words and imagery.

Did Lundin’s conversion trigger a wider transformation? His bandmate also became a Catholic. And other Catholic extreme metal bands followed, such as Voluntary Mortification and Erlösung (who perform a unique rendition of the hymn “Silent Night”).

But it’s hard to discern whether this signals a genuine revival because subgenres like black metal are small, obscure and thrive underground. Reports of conversions are hard to corroborate. They may be short-lived or intended only as provocations. But one thing’s certain: there is a well-trod path from hailing Satan to saying Hail Marys.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply