When I joined The Spectator in 2000, the office was in Bloomsbury, in a four-story Georgian house, and the further down the building you went, the more stylish, the more Spectator (I thought), everything became. On the top floor, blinds drawn, sitting in the half-dark, was Kimberly Fortier, the American publisher, often in long meetings with media alpha males. She would soon be married to the publisher Stephen Quinn and having an affair with former British home secretary David Blunkett, but was always looking to widen her portfolio.

One floor down was former British prime minister Boris Johnson, then editor of the magazine, mostly immersed in meetings of his own with associate editor Petronella Wyatt. We’d sometimes find him on the landing, staring mistily into the middle distance. “Petsy looks like a Bond girl. Doesn’t she look like a Bond girl?” he’d ask nobody in particular.

The real Spectator was below the editor’s office: Stuart Reid, Mark Amory, Clare Asquith, Liz Anderson, all squashed into a tiny ground floor room; Michael Heath in Prada and a round felt hat, drawing ceaselessly in black Indian ink, whistling Charlie Parker through his teeth.

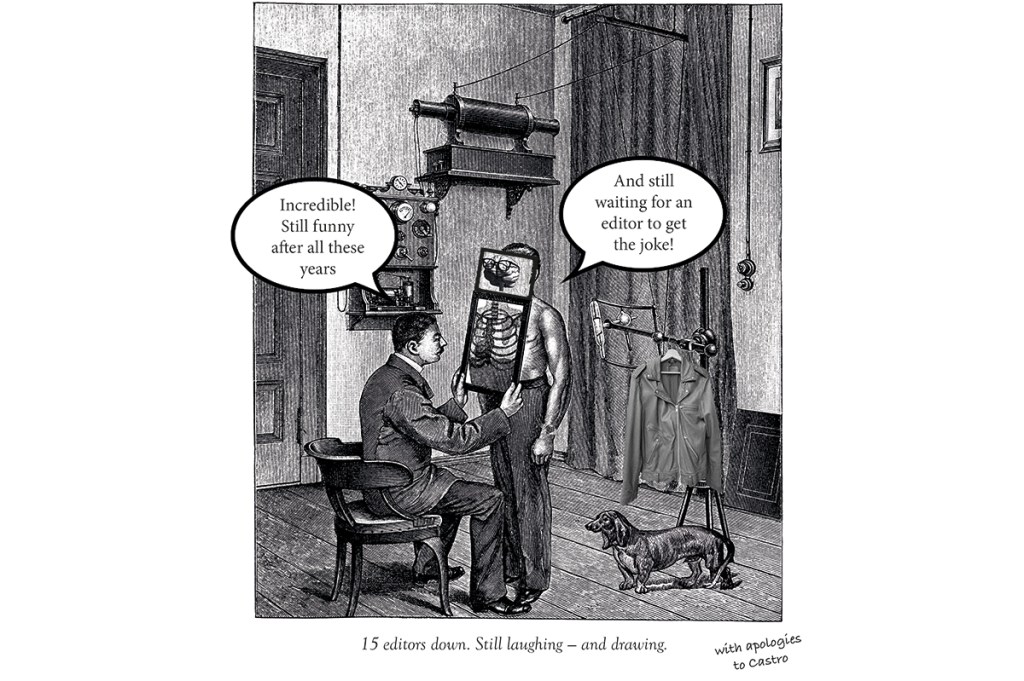

Even then, he was the longest-standing contributor. “I had my first cartoon accepted when I was 15, in 1950,” he says. “How’s that?” Now Michael is 90, The Spectator is pushing 200 and, he says, “I’ve been at the magazine longer than most of its columnists have been alive.

“Think of that! Actually I think I’m the world’s oldest working cartoonist or something… is that a good thing? Sometimes I feel like my brain is melting.”

Back in 2000, Michael and I would walk around Bloomsbury at lunchtime, he pointing out every trend: trousers worn down around the mid-bum, the new fashion for skinny jeans – details that would then appear in the afternoon’s drawings. We’d walk down Rugby Street where he’d lived as a young man and often talk about women. “I came home one evening, and the missus had changed the locks. And she’d sold all my furniture! Nightmare!”

Michael is back on Rugby Street these days, with a new wife, Hilary, who won’t change the locks. And that’s where we are now, side by side on the sofa, on the eve of the 90th birthday, talking about where it all began. What makes a good cartoonist? “Well it helps to be neurotic, lonely and an only child, preferably with some talent for drawing,” he says.

Were you a lonely only child? “Yes, I suppose so. My mother used to sleep all afternoon and I don’t think my father ever said a word to me. He drew comic strips too – not funny stuff though. Cowboys and Indians for boys’ magazines.”

Why didn’t he talk to you? “I don’t think I was his son.” In all the years we walked about, I never heard this one. Whose son were you? Michael looks pensive. “Well, a man turned up at our house once every year. They called him Dogsbody. He smoked continually, hand-rolled cigarettes with his name on. He and my mother, they’d obviously had an affair. He’d bring all this stuff, for me, toys, but soon as he went, my father gave the toys to people next door.”

After the war, London began to loosen up and the young Michael Heath with it. “I didn’t want to be like my mother and father, so when all the boys and girls began to run around town and go dancing, I decided to draw them. The wacky shoes and the hair. There was a newness about everything. Everybody was having affairs, all over the place, but drugs hadn’t taken over yet. Everyone talked and laughed.”

Don’t people talk and laugh today? “They’re too busy texting to talk, aren’t they? And they can’t take a joke. You can’t joke about women, fat people, thin people. Even sex is a very serious business now, all about identity. And everyone’s terrified of saying something which will upset people.”

This was absolutely not the case in 1970s and 1980s Soho, where Michael and Jeffrey Bernard, The Spectator’s first “Low life” columnist, spent their days and where upsetting people was very much the thing. “We’d go to the Colony Room, and Ian Board [the barman and later the owner] would greet you with: ‘Oh fuck off, c**t,’” says Michael. “Francis Bacon would be at the bar, cutting people to shreds. Some people couldn’t take it. They were destroyed.” Michael did a cartoon strip back then called “The Regulars” for the satirical magazine Private Eye. “Half my ideas came from sitting in the French House and the Coach and Horses, listening to Jeffrey and to other people,” he says. “You didn’t need to draw parliament – you could find every kind of idiot in Dean Street.”

Bernard once said of Michael: “Heath doesn’t talk much. But he listens. Then he goes home and draws what you said – badly – and everyone thinks it’s genius. Bastard.”

Michael says now of Bernard: “He could write. However pissed he was, he could write. And even though terrible things happened to him as a result of the drink – I mean, he had half his foot taken off – women were still attracted to him for reasons unknown to me. Intelligent women! They used to bring him food from Fortnum’s and he’d be terrible to them. They loved it. I don’t understand women.” Christopher Howse, Michael’s old friend, explained the appeal of Soho in conversation with him in 2018: “It was just great fun, despite the misery. It was funnier than any situation comedy could be, because you knew all the people.

“The things that happened were astonishing and it always ended in tragedy, breakdown of health, falling down the stairs. Death – that was the automatic ending. But in the meantime it was great fun.”

“I was with Jeffrey when he died,” says Michael. “If you’ve never been with an alcoholic you wouldn’t understand, but that’s how it is. They drink themselves to death. In the end he just overdosed on whatever it was he was taking. ‘I never felt so happy in all my life,’ he said. And died.”

But how did you survive? How did you keep on observing and drawing through all the drinking? Gags, strips, vast detailed satirical drawings, Private Eye, The Spectator, London’s Mail on Sunday. “I always worked. I was working all the time and still I am,” Michael says. “You know, I haven’t got the guts to stop it.”

The editor who invented the modern Spectator was Alexander Chancellor and when he died, the satirist Craig Brown wrote of him: “The lunches, the enjoyment, the fun, were all part of his armory. Beneath it all, that brilliant mind has never stopped whirring.

“More puritanical editors, priggishly insulated from the world outside, had nothing of Alexander’s verve and excitement.”

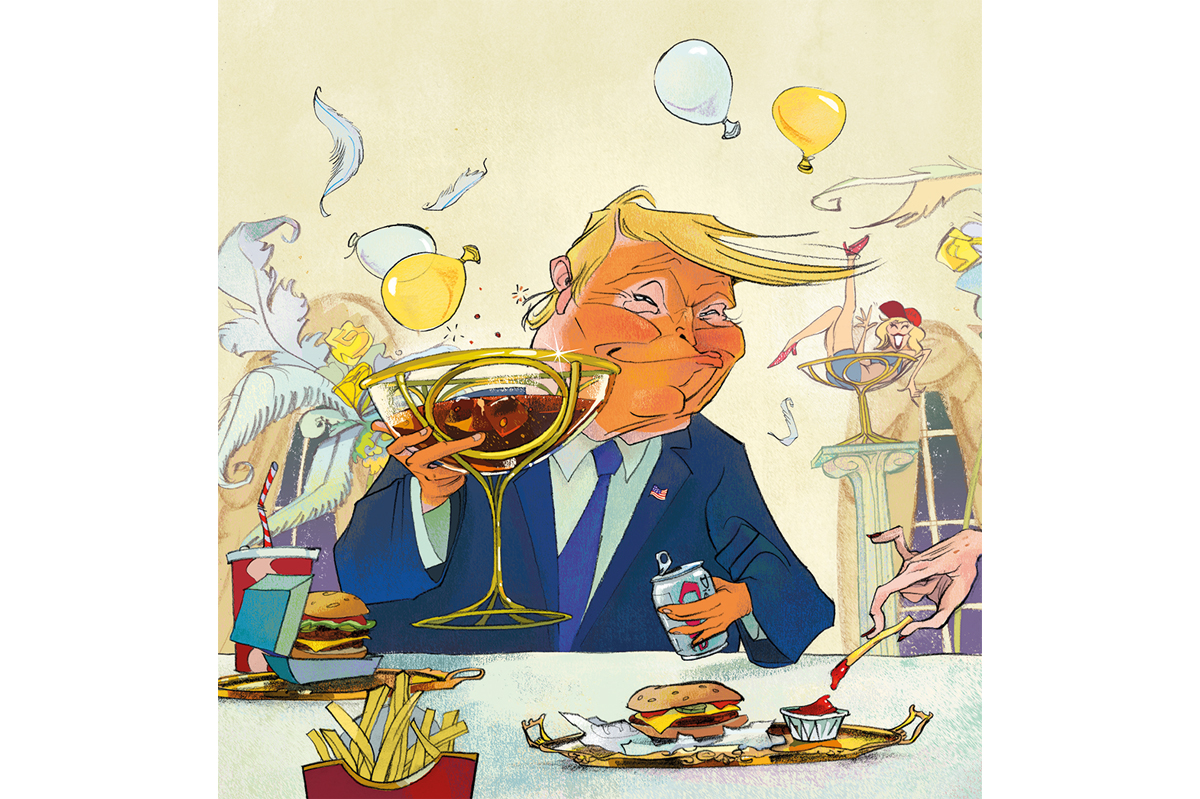

The same is as true of Michael. Through all the wine, the wives, the changing of locks, he never stops. Drawings pile up around him, satirical, joyful. Your cartoons can be cutting, but the drawing never seems angry, unlike other cartoonists, I say, not naming names. “You mean Gerald Scarfe and Steadman and that lot?” says Michael. “All those people shouting and falling over, shrieks and splatters? The trouble with that is, it’s always the same picture, isn’t it? It gets old.”

We get off the sofa and cross the road to the Rugby Tavern, where Michael jokes loudly about the things you can’t joke about anymore. “All this sort of non-binary stuff. It’s everywhere, isn’t it? I mean, get her, over there!”

I tell him how much I love his ongoing Spectator strip “The Battle for Britain” – surreal, outrageous and often weirdly prescient. Michael was mocking woke a decade before the rest of us caught up. “You can’t say anything these days,” he shouts at the Rugby Tavern barman, as he reaches for his glass of white. But he can, he always has, and he does.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply