I am in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan. I am standing in a historic complex of madrasas and mosques, courtyards and dusty roses and I am staring at the “oldest Quran in the world.” It is a strange and enormous thing: written in bold Kufic script on deerskin parchment; it was supposedly compiled by Uthman ibn Affan, the third Caliph of Islam, who was murdered while reading it. And so it is, as I linger here and reverently regard the Book, while scrolling my phone for more fascinating info, that I discover the world’s oldest Quran is actually in Birmingham.

Yes, that’s right, Birmingham, England. It’s probably in some obscure library, lodged between a thesis on post-colonial emojis and a flyer for Falafel Night. I can’t help feeling Birmingham should make more of this, maybe to distract tourists from other parts of Birmingham.

In other words, the Uzbek claim is a fib. Or at least a fabulation, an exaggeration, a concoction. But that, in a way, sums up this remarkable and compelling country, with its history of illusions and cruelties, Islam and Marxism, terrifying materialism and lyrical mysticism. It is a place of dreams and deceptions, all of it alongside some of the most spellbinding, beautiful cities on Earth.

Tashkent, however, isn’t one of them. Designed as something of a showpiece city for communism in Central Asia, it boasts big wide boulevards, bragging monuments, impressive metro stations and a lot of concrete. Nonetheless, there are raisins of prettiness amid the stodgy architectural plov. (Plov is the national dish around here: a kind of meaty, slow-cooked paella: it’s an acquired taste.)

One of these occasional gems is Tashkent’s theater, built in Islamo-Uzbek style and designed by the man who did Lenin’s mausoleum in Red Square. It’s as if the Alhambra mated with a coke dealer’s palace. Try to catch a performance, if you can.

And now, the stomach stirs. You can do a lot of walking in sprawling Tashkent. And when you’re hungry, there is only one place to go: Chorsu Bazaar, with its concrete UFO-ish dome protecting a compelling warren of cafés, pop-ups and fruit shacks, selling pickles and plov and cumin and steaming “Uzbek lasagna.” There are sun god bread-wheels and sliced fresh baklava, warm spicy samosas and fresh pomegranate juice – marvelously tart and refreshing on a hot sunny day, of which there are many.

There is a sheltered hall right by the market stalls where you can eat your food washed down with Coca-Cola or tamarind cordial, or maybe a cold beer from the nearest booze-friendly corner shop. There’s been a market here since the second century, and it’s likely changed a bit: they no longer trade Circassian slaves with the Tibetans, but it still thunders along, merrily. Uzbeks say a good market is like your mother and father. If so, this family is particularly welcoming, albeit very noisy.

Onward to Samarkand via, I am not joking, high-speed train. The Uzbeks have linked all their main cities with high-speed rail, including the tourist honeypots of Samarkand and Bukhara, and, very soon, Khiva. The trains are clean, fast, efficient. They are also incredibly cheap, like everything in Uzbekistan, and decidedly popular. Book weeks ahead or get your tour operator to do it.

What to say of Samarkand that has not been said before? Let me have a go. The historic sites are marvelous, from the extraordinary 15th-century Ulugh Beg Observatory, which includes a huge underground sextant like the buried curving rib of a god-giant, to the 7th-century pre-Islamic murals of Afrasiab, the city under Samarkand.

These intoxicating murals, now in their own museum, depict a wildly cosmopolitan, almost psychedelic, vision of a lost Silk Road world, where Chinese princesses ride elephants, Koreans in fur hats bring tribute, and Indian dignitaries wave incense at Central Asian deities. Peerlessly strange, brilliantly unforgettable.

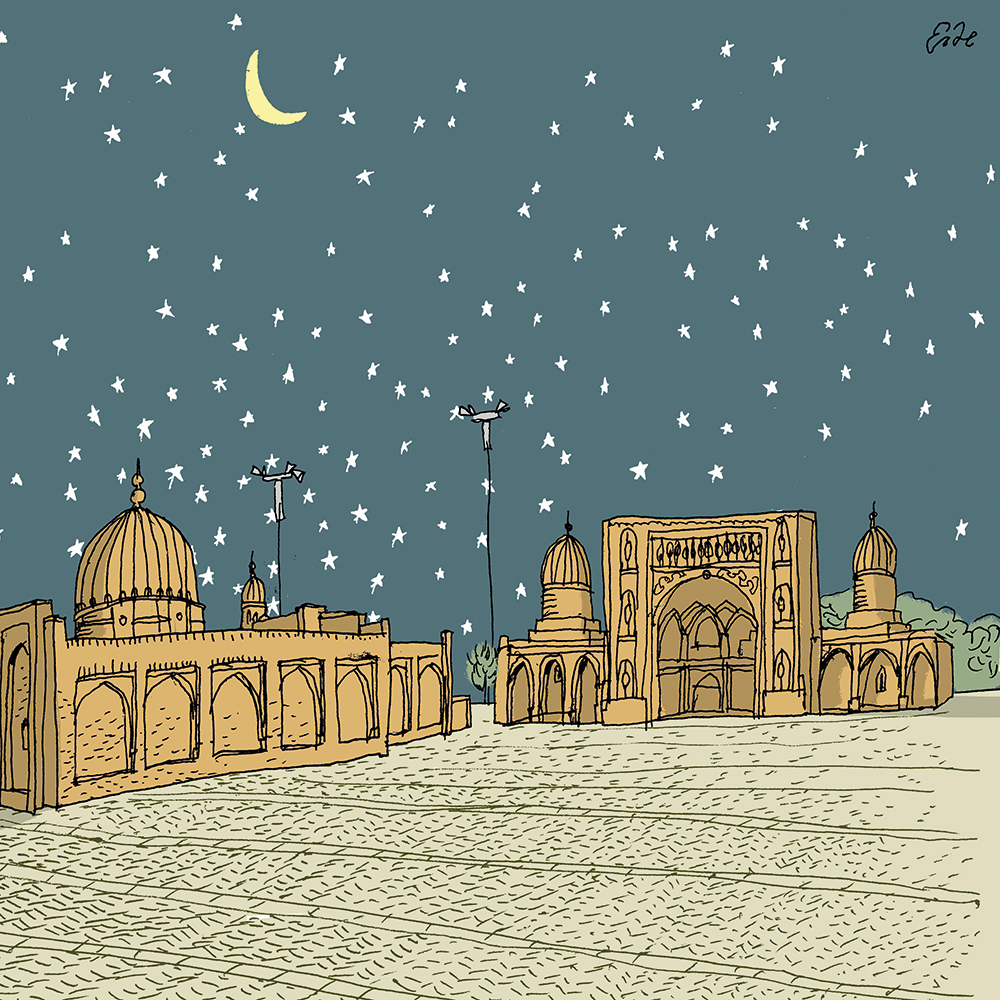

And then there’s central Samarkand. And the Registan. If you’ve ever seen photos of Samarkand, this is what you will have seen, and for good reason. By day, the Registan must be one of the most beautiful public spaces in the world. It rivals St. Mark’s in Venice. Exquisitely harmonious with its echoing arches and minarets, its ochers, cobalts and turquoise, the three madrasas and mosques are decorated with dancing lions and spinning stars, like a trio of wonky Taj Mahals dunked in a tub of Isfahan blue paint and decorated by Van Gogh during his starry night phase.

By night, the Registan is arguably even lovelier. The Uzbeks have mastered the art of nocturnal lighting. The mighty square becomes a swooning dreamscape, with the Sher-Dor Madrasa softly lit in dusty yellow and pomegranate red, shimmery and sad-sweet, even as kids quietly play beneath the spotlights, overseen by indulgent parents licking purple ice creams.

Before you leave Samarkand, there is one other must-see: the Tomb of Tamerlane, the fearsome warlord who conquered half of Asia in one hell of a life. Known as the Gur-e-Amir, the gilded, golden-tiled interior rivals anything at the Registan. The great man lies forever under a slab of nephrite jade, beneath a dome of lapis, enamel, vivid calligraphy and dusky starlight. Or so it feels.

Our last stop is Bukhara, which is only fitting as this is where old Uzbekistan finally fell. The city is like the Central Asian Cambridge to Samarkand’s Oxford. Softer, more delicate, perhaps sadder, more ethereal. In the center, you’ll find a mini-Registan and also some excellent poolside cafés for shish kebabs and tolerable wine. From here, mazy lanes extend into the old Jewish town, full of whispered rumors, all the way to the famous Ark, a brooding citadel that symbolizes the city.

But my favorite spot, it turns out, is on the outskirts, at the summer palace of Amir al-Mu’minin. The Commander of the Faithful, Khan of the Manghit Dynasty, Shadow of God on Earth, Sultan of the Faithful and Sword of Islam. And the Last Emir of Bukhara.

In this quixotic palace, half Islamic, half European, the very last emir lived a quite ridiculous life. Born in 1880, he was surrounded by eunuchs, mystics, torturers, gramophones and a harem rumored to number in the hundreds. He believed in djinn, held séances, smoked opium and consulted astrologers before making policy. He also wrote decorous Persian poetry and kept a wind-up automaton that bowed on command. In 1920, the Bolsheviks came for him, and he fled into the deserts of Afghanistan with trunks of gold, carriages of terrified dancers and prayer books coated with poison. It is said that the emir died in Kabul in 1944, writing poignant verses for his lost Bukhara, even as he drank English gin in total silence.

Like the emir, my time here is almost done. So I retreat to the shady side of the last Emir’s last harem. Once I would have been thrown in the infamous pit of vipers and spiders for my effrontery. These days, it’s a charming café. I recommend the excellent cakes.

Sean was a guest of Cox & Kings, which offers a 12-day small group tour, Uzbekistan: Heart of Central Asia.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply