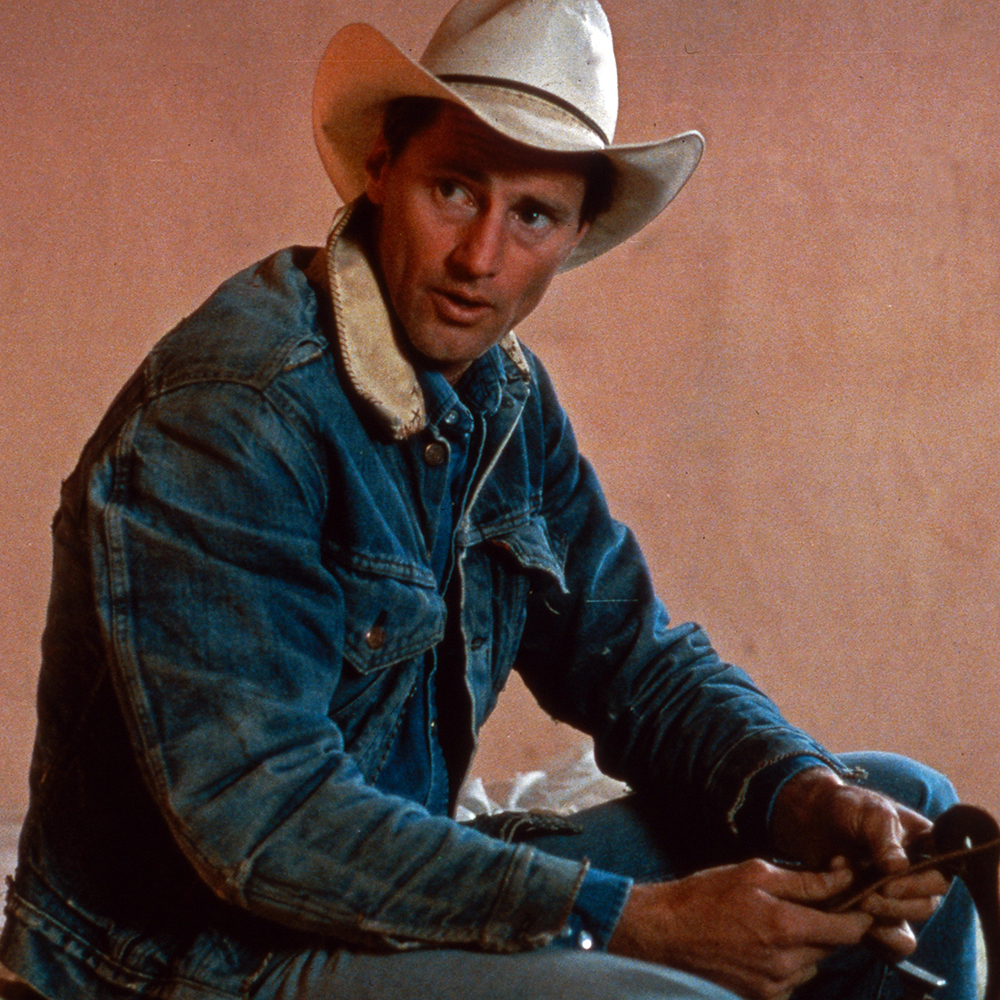

Sam Shepard and I crossed paths several times when we were both living near Charlottesville, Virginia, he with Jessica Lange and their family, and me as a student at the University of Virginia. He towered over passersby on the Downtown Mall, walking as if invisible spurs should be clinking on his bootheels, mane of dark floppy hair pushed back off his forehead and behind his ears, keen eyes above a quick grin. I last saw Shepard 20 years later, having a coffee and reading the Daily Racing Form in a Greenwich Village restaurant; he looked even better then.

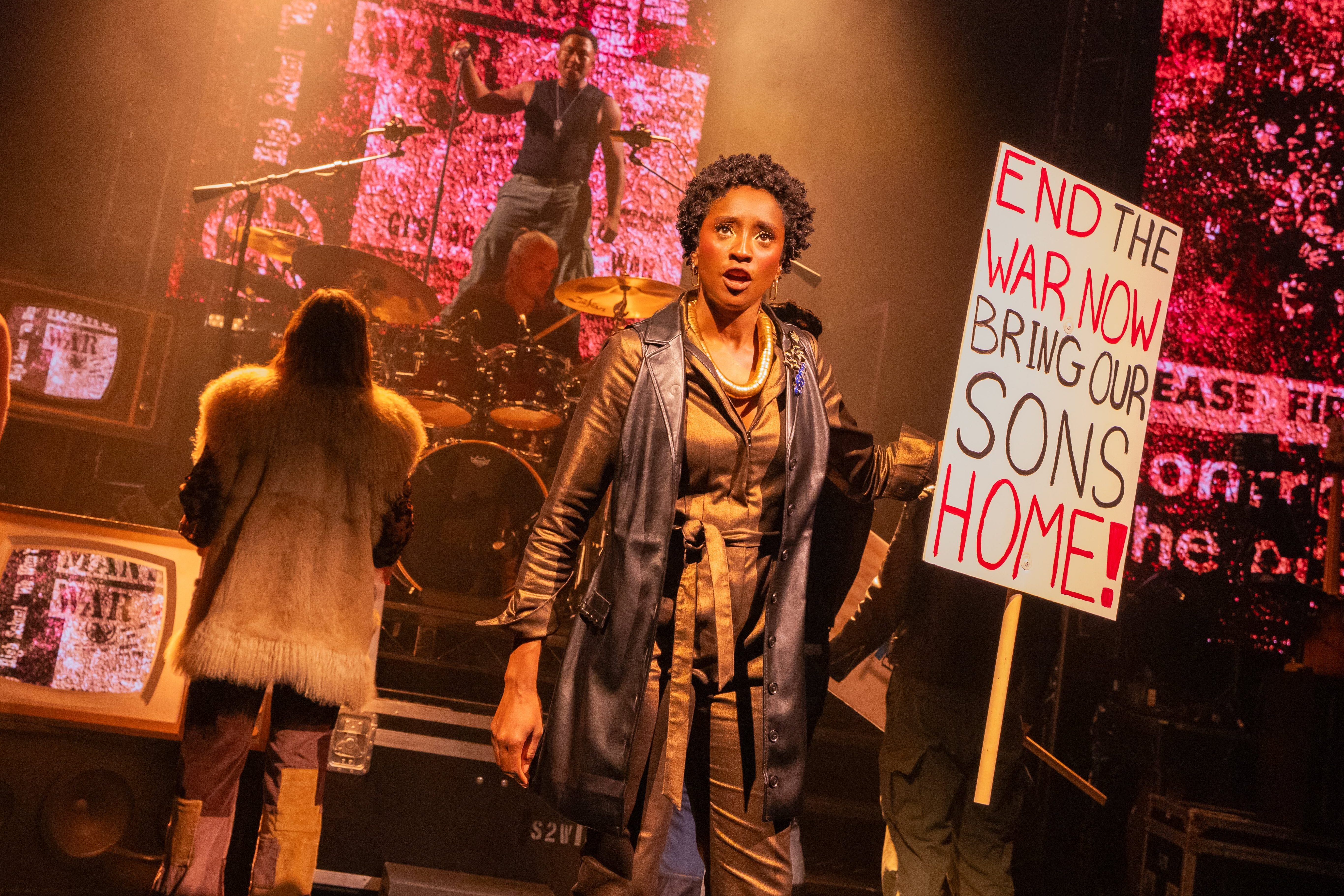

He was a true Renaissance man. There he was, on Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue tour in 1975, charged with writing a screenplay for a movie somehow set in the concert tour. Shepard had been hired by Dylan despite (or perhaps because of?) his 1967 Melodrama Play, in which Duke Durgens tries to write a hit song in a room decorated by posters of Dylan and Robert Goulet with their eyes scratched out.

Joni Mitchell joined the carnival bus of musicians, poets, writers, roadies, family and guests in New Haven, Connecticut on November 13 that year. Two nights later, in Niagara Falls, she and Shepard began an affair about which she immediately wrote a song titled “Coyote.” The song was a hit and became the lead single from her 1976 album Hejira, now regarded as one of her finest. Mitchell’s nickname for Shepard stuck – and is the title of Robert M. Dowling’s detailed and dramatic biography of this hard-to-handle and completely compelling playwright, actor, musician, director, poet.

Samuel Shepard Rogers III was born at an army training camp in Highland Park, Illinois, during World War Two to a mother he adored and a father who was a decorated Army Air Corps pilot and a savage man when drunk, which, unfortunately, was often. Young Steve, so called to differentiate him from Sam Sr., spent his early school years living with his mother’s aunt in Pasadena until the Rogers family moved to their own home – an avocado farm in the San Gabriel Valley.

It was a hard life: Shepard worked the farm, earned money tending livestock on neighboring ranches (he wanted to be a veterinarian when he was a boy), and disliked school until he read Samuel Beckett’s plays as a college freshman. He was “knocked out of the saddle,” as he put it, by Beckett. When he read Waiting for Godot, Shepard said: “It just struck me suddenly that with words, you could do anything.” He wrote his first play, The Mildew: A One-Act Comedy, derived from Beckett and his other hero Eugene O’Neill, quickly that fall. However, his good looks and acting ability led him onto the stage instead. For the rest of his long career, he would continue to write plays and act in them and movies. As the book’s subtitle suggests, Shepard had more lives than a cat – and all were dramatic.

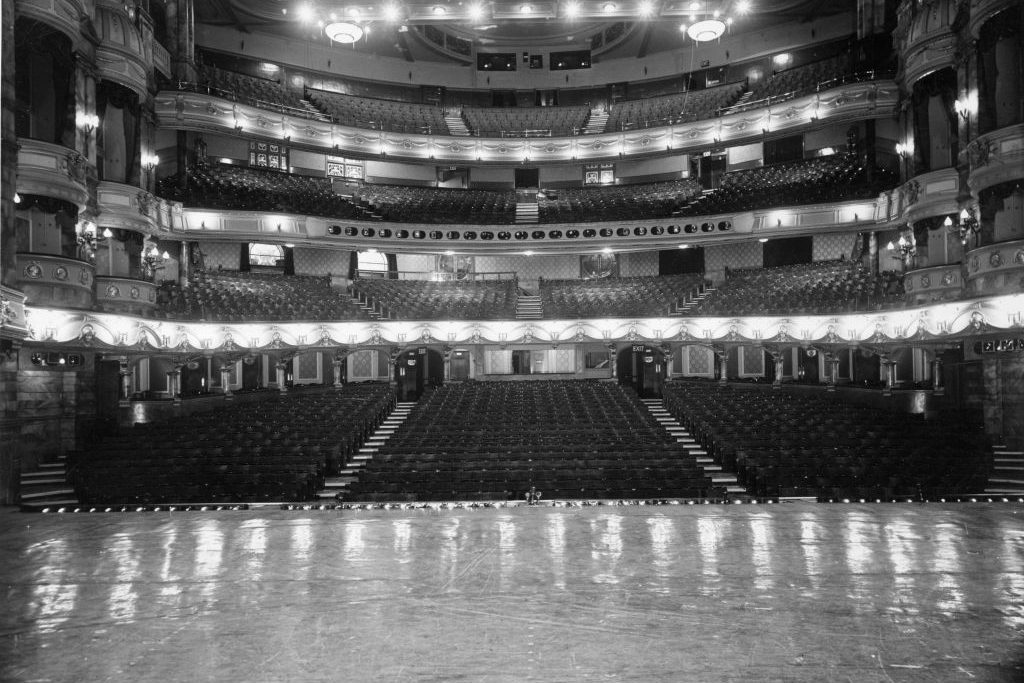

Though he was always a westerner, and in his plays and film roles became an avatar for the still-wild, contemporary American West, Shepard moved to New York City in 1963. Later, he lived across the country, from Minnesota to Charlottesville, Santa Fe to the San Francisco Bay area to Kentucky, and had a house in rural Nova Scotia for many years. But Greenwich Village and the East Village remained home: the place where he first made it as a very young man and where his many plays most often premiered – not on Broadway, not even after he was famous, but in basements and warehouses and loft spaces, at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, at La MaMa and other beloved experimental neighborhood theaters for which Shepard had nothing but affection and gratitude.

In the summer of 1964, Ellen Stewart of La MaMa and Ralph Cook of Theater Genesis both agreed to put on Shepard’s work. Shepard was busing tables at the Village Gate. The music he was listening to there inspired “rhythm discoveries in space and time through packing up words and stretching them out along with their size and shape and sound. Once this got started, lo and behold there came phantoms and ghosts speaking these words… and things began to crackle.”

The Rock Garden, an absurdist play full of graphic sex talk about growing up in California, and Cowboys, about two boys playing cowboys and Indians, were panned by most critics but praised by Michael Townsend Smith, chief critic of the Village Voice. Smith said that the 20-year-old playwright was “working with an intuitive approach to language and dramatic structure and moving into an area… where character transcends psychology, fantasy breaks down literalism, and the patterns of ordinariness have their own lives.”

This would remain true of all Shepard’s plays: even the most hallucinatory and experimental were based, somehow, in his own experiences, with those patterns of ordinariness taking on wild lives.

Dowling, who is also a biographer of Eugene O’Neill, analyzes individual plays while paying keen attention not only to their language and critical reception, but the circumstances of their writing and first performances. Shepard’s La Turista, for example, is a delirium more than a play, about a young couple who get sunburn and dysentery in Mexico. To know that it was based on a terrible trip to Mexico in which Joyce Aaron and Shepard got so sick in a hotel room in Oaxaca that they could not leave it for three days and, having no toilet, threw up in the sink, often together, often laughing, and that the play was first staged in 1967 with Aaron and Sam Waterston in the lead roles, and required chicken heads to be cut off on stage (fake birds and lots of stage blood sufficed), is the kind of background that enriches rather than annoys.

Though professionally Shepard soared early and remained successful for 50 years, Dowling doesn’t shy away from showing how he kept going in cycles in his personal life. He would leave one woman (and sometimes their children) for another, then repeat. Shepard’s most significant partners were actresses: Aaron, who introduced him to Joe Chaikin, the Open Theater and to Toby Cole, his first literary agent; Nancy Mandel of the Group Image; O-Lan Jones, his first wife; Jessica Lange, his partner for 30 years.

Musicians flamed briefly in his life: notably Mitchell and before her Patti Smith, who after their turbulent affair became a lifelong friend. Shepard was a musician, too, a drummer who performed with the Holy Modal Rounders. He and the Rounders played at his November 1969 wedding, at St. Mark’s Church, to a pregnant, 19-year-old Jones – Shepard and the band, writes Dowling, all on “purple tabs of LSD.” The best man, Bill Hart, knocked down both bride and groom, the officiant, Allen Ginsberg, could hardly be heard above the applause and yelling – and Shepard finally picked up the bride and carried her out of the church to safety.

In 1984, after many infidelities, Shepard left Jones and their teenage son for Lange. His drinking would eventually end their long relationship. After a romance with his twenty-something assistant – on which his play The One Inside is based – ended in 2015, the 71-year-old Shepard said, “I’m only beginning to realize how I’ve ruined every relationship with women in exactly the same pattern and that booze is the centerfold.” This pattern, even when known, never stopped the tall, dark and handsome Shepard from being immensely attractive, in his best movie roles as well as in life. His looks and acting ability got him cast in films and television series for 40 years, from his turn as Cowboy, the lover of a character played by Sara Dylan, in Renaldo and Clara (1978; the Rolling Thunder Revue movie for which he didn’t, in the end, write a screenplay) to the art thriller Never Here (2017). Shepard appreciated the money: Hollywood salaries for detritus such as Swordfish (2001) and The Pelican Brief (1993) allowed him to keep writing plays. “Not having a play to write is like being without a friend, homeless, in a state of wandering,” he wrote in his diary. He wrote almost 60 scripts, winning the Pulitzer Prize for Buried Child in 1979 – the first off-Broadway play ever to receive the accolade.

Shepard is an enduring playwright because he knows what frightens us, and understands how this makes us feel. The critic Richard Gilman was right: Shepard’s titles scare you – Buried Child, The God of Hell, Suicide in B Flat – and so do the characters: Forensic, Ice, Blood, Blade. The women are long-suffering, superior, and sometimes flame with passionate intensity, like 12-year-old Emma in Curse of the Starving Class (who gallops her horse into a bar, pistols blazing). The men are impotent, often drunken patriarchs and have corroded, corrosive sons – with some lone characters, such as Hobart in Kicking A Dead Horse, fusing these generational stereotypes.

What it is impossible to do with Shepard is ignore the fear in his plays – and his intense sympathy with it in humans. Dowling is right that “fear is the guiding principle of Shepard’s work – fear of authority, fear of flying, fear of war, fear of climate change, fear of failure, fear of abandonment, fear of loneliness, fear of heredity, fear of identity, fear of death, and fear of our escalating estrangement from reality.” True West and Fool For Love are the plays that most encompass the sweep of all these fears, and that is why they’re my favorites of his.

When he died in July 2017, aged 73, of the complications of what Dowling reports was progressive muscular atrophy, a copy of Beckett’s Endgame was on Shepard’s bedside table. His old friend Stephen Rea had invited him to appear in the play as Hamm, to Rea’s Clov; Shepard loved the idea, but had had to decline because he didn’t trust himself to remember the long-familiar lines. It would have been a hell of a finale, one that would have suited his connection to the inspirational playwright he once teasingly termed “the other Sam.”

Dowling’s superb accounting of Shepard’s stories, both lived and written, left me thinking of Shepard’s last lines in “How I Look To You,” from his 1979 performance piece Savage / Love: “Which presentation of myself / Would make you want to touch / What would make you cross the border.” The answer, where Sam Shepard is concerned, is all of them.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply