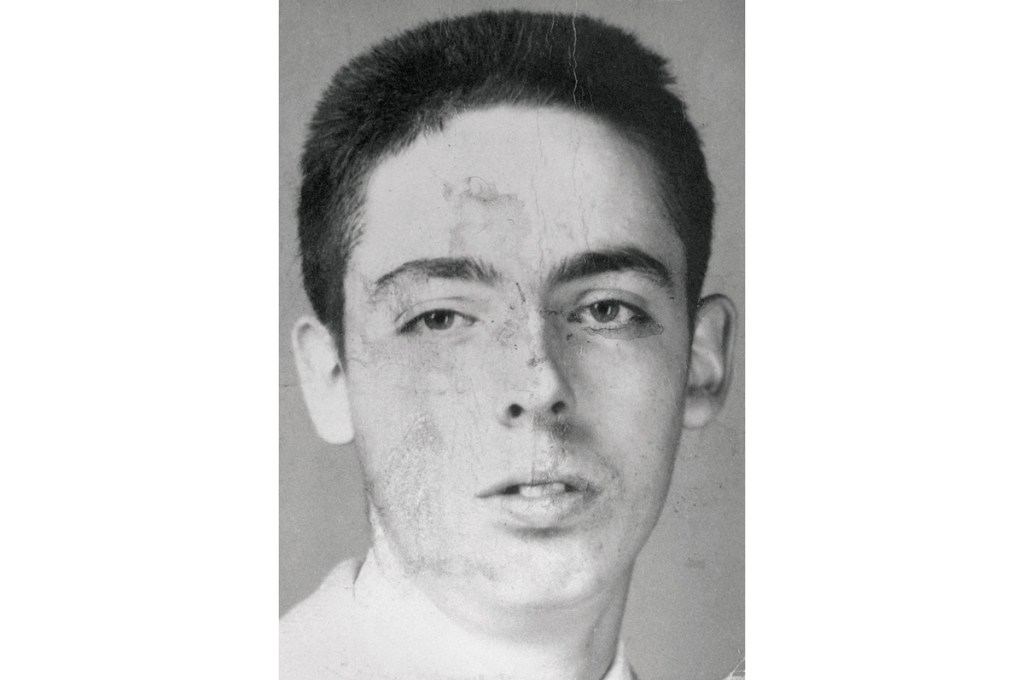

And just like that, after an excruciating 12-year hiatus, the literary world’s answer to Harry Houdini is back. Thomas Pynchon, that notorious recluse, has resurfaced with Shadow Ticket, a tricksy Prohibition-era detective caper that is by turns exhilarating, exasperating and inimitably Pynchonian.

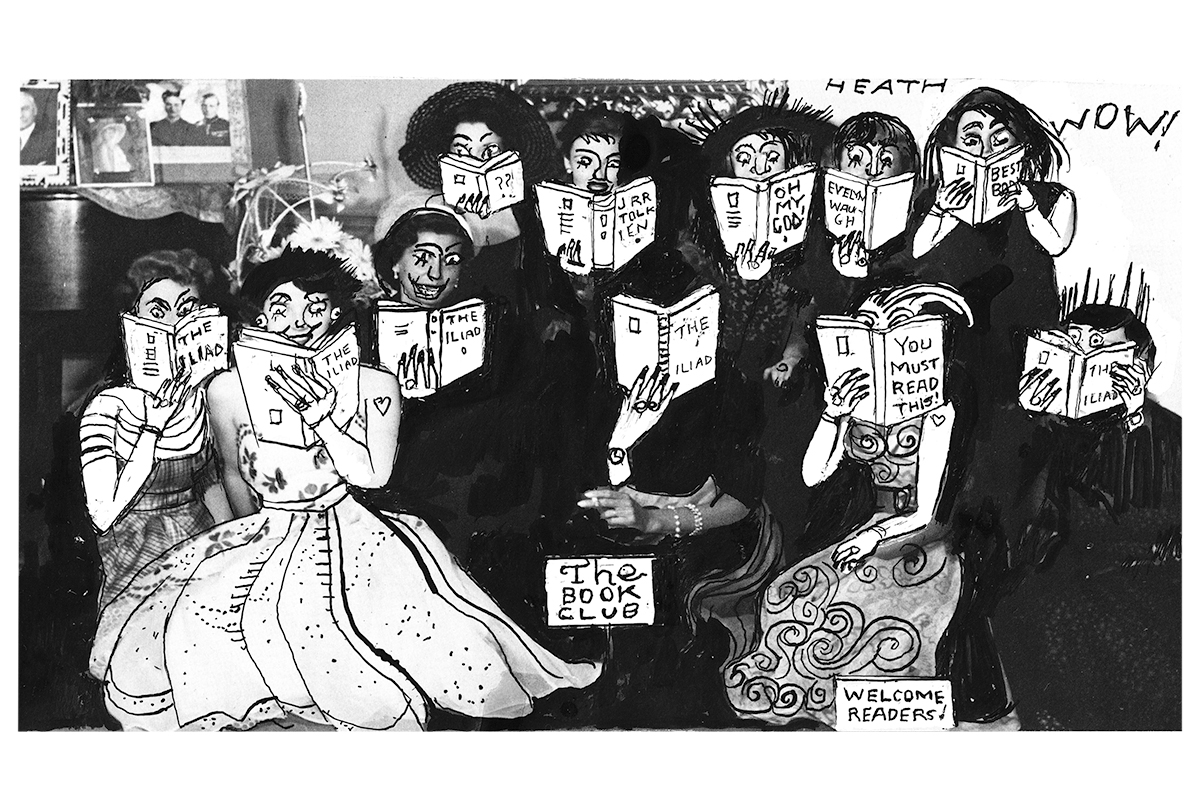

A new Pynchon novel is simultaneously a reviewer’s wet dream and feverish nightmare. There’s so much to unpack, you’re never going to do it full justice after a single reading. This is, after all, the writer famous for Byzantine, convoluted plots which zigzag their way across entire continents, ideologies and historical epochs, brimming with mysterious entities and delightfully nutty characters.

Shadow Ticket is no different. Set in the frenetic years leading up to World War Two, it hurtles from Midwestern speakeasies to Central European hinterlands, scooping up along the way a rogues’ gallery of occultists, double agents, Soviets, Nazis and swing musicians all orbiting a plot that, at least nominally, involves a private investigator searching for a runaway heiress named Daphne Airmont, daughter of “the Al Capone of Cheese.”

All the old tricks are here: sing-songs, slapstick, the author’s encyclopedic obsession with old movies (“the Talkies”), culminating in a dense historical pastiche stuffed with more references than most writers manage in a career. Yet at 292 pages, this is a slimmer, ostensibly more accessible novel than the great works Gravity’s Rainbow, Against the Day or Mason & Dixon. In theory, that should make Shadow Ticket tauter. In reality, it often feels like a sprawling Pynchon epic Ozempic’d into a thinner dust jacket and bursting at the seams. With a gazillion characters to keep track of (at least a hundred, before I lost count), it’s definitely an adventure, even if it wants space to breathe.

Our hapless guide through the madness is the Chandler-esque gumshoe Hicks McTaggart, a former strikebreaker turned private eye whose résumé is, by his own account, “one high-risk Orangutan job after another, always in the service of someone else’s greed or fear.” He is hired to track down the AWOL heiress – “or at least that’s what the ticket says, but I keep hitting detour signs” – and promptly finds himself drugged, shanghaied and bounced around a world that seems to have lost its mind.

What starts in 1930s Milwaukee tumbles into a delirious trans-European chase involving outlaw biker gangs, hired assassins, vampires, female robots (“Robotka”) with crushes on golems, “rogue nuns in civilian gear two-stepping with bomb-rolling Marxist guerrillas,” Hungaro-Croatian terrorist training camps and enough incestuous love triangles to make your head spin.

It’s gloriously absurd, of course, but also occasionally exhausting. Some chapters read like a series of Pynchonian vignettes as if the author, now in his late eighties, is simply following his own fascinations wherever they lead without much attention to pacing. One minute we’re in a Nazi bowling alley dubbed the “New Nuremberg Lanes,” the next we’re told of pigs in sidecars and dogs flying autogiros. It is, admittedly, heaps of fun, but at times the novel seems driven by a single, anarchic principle: why stop there? If there’s a risk of losing readers along the way, Pynchon doesn’t seem to care.

It doesn’t help that Hicks is a weak narrative anchor. If Doc Sportello, the weed-hazed private investigator of Inherent Vice, embraced coincidence and absurdity with curiosity, Hicks is his more apathetic descendant, seemingly incapable of just going with the flow. That said, he certainly has his charms – he likes bowling and is an improbably good dancer; he has a sweet relationship with his protégé, Skeet, and has become so sentimental he’s gone off punching Bolsheviks for cash-money altogether. While likable, our protagonist remains an oddly passive (even gooey?) center to what is otherwise a riotously overactive storyline.

Yet amid the cacophony, Pynchon’s magical prose still gleams. There are moments of lyrical transcendence – the kind of sentences only he could write – such as when a character’s laughter “streams across the altitudes like a white silk aviator’s scarf,” or when he muses, with deceptive simplicity, that “objects are open to every vibration that comes their way… if a human soul can be defined as a structure of memories, if to ‘read’ an object is somehow to gain access to what it remembers, then how can we begrudge it a soul?” These flashes of grace remind us that Pynchon handles questions of existentialism and metaphysics with a lightness of touch (not to mention humor), not to be found elsewhere in contemporary American fiction.

If Shadow Ticket is indeed the last ever Pynchon novel, it’s a zany and unapologetic capstone. Wide-ranging, clever, funny and full of the author’s eccentric obsessions, it’s anything but a slog. For readers coming to Pynchon for the first time, this one may leave you scratching your head but that’s no reason to avoid it. It’s worth reading for its sheer inventiveness and unhinged energy alone. Who knows if this sly, enigmatic fox has another, more bombastic last hurrah up his sleeve? Fans can only hope. One thing’s for certain, there is nobody, nor will there ever be, quite like Thomas Pynchon.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply