“A Desecrated Serenity” at the Hauser & Wirth gallery chronicles the remarkable seven-decade career of Sir Don McCullin CBE, Britain’s most celebrated photojournalist, who turned 90 last month. Known for his unflinching documentation of war, famine and human displacement, McCullin is widely regarded as one of the most important photographers of the late 20th century. This exhibition, his most comprehensive US presentation to date, brings together over fifty works and rare archival materials.

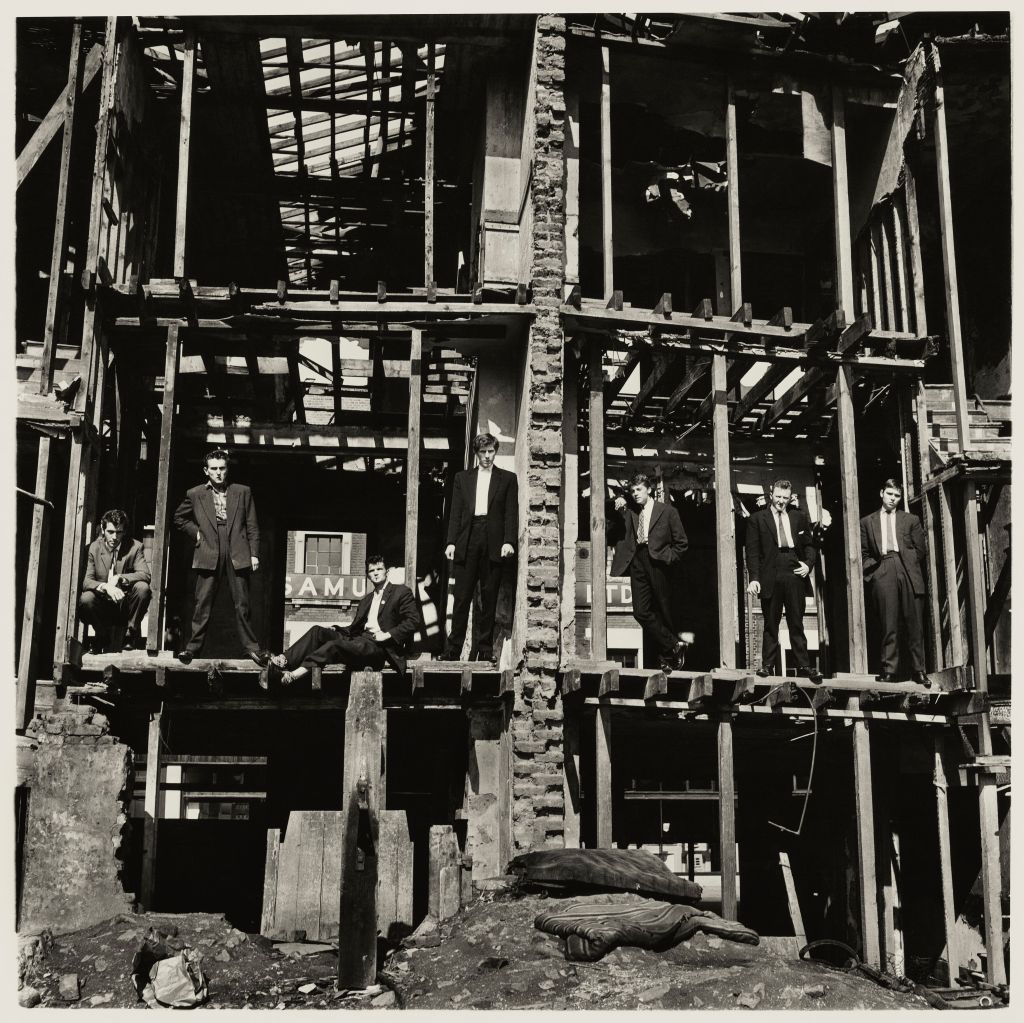

McCullin, born in Finsbury Park, North London in 1935, first picked up a camera during National Service in the Royal Air Force, while working as a photographic assistant in aerial reconnaissance. But he failed the Air Force trade test to become a photographer and wouldn’t get his first professional break until 1958, when his first published picture – of a London gang called “The Guvnors” – appeared in the Observer newspaper. This led to a contract with the paper which, in 1963, sent him on his first official war assignment to Cyprus, where he experienced his “baptism of fire” as a photojournalist.

Between 1966-1984 McCullin worked for the Sunday Times as a staff photographer, a tenure which took him to the frontlines of war across Greece, Vietnam, Cambodia, Biafra, Bangladesh, Northern Ireland and Beirut – infernos where he produced some of his best-known images, such as “Shell shocked US Marine 1968” and experienced several close brushes with death. One archival material on display is the Nikon F camera McCullin was holding to his eye when it absorbed a bullet from a Khmer Rouge soldier’s AK47.

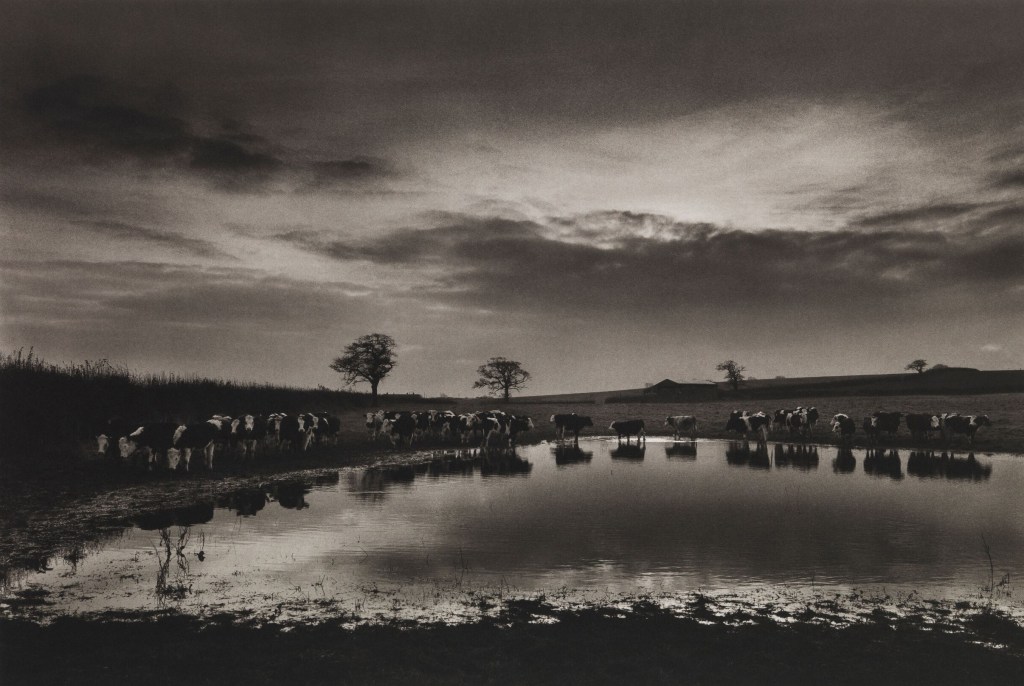

“A Desecrated Serenity” is spread over two rooms. Harrowing images of war and suffering hang alongside stark industrial landscapes of Northern England in the fifties and sixties, portraits of The Beatles from their “Mad Day Out” photo session and compositions from his personal travels across India, Indonesia and the Sudan. Later work includes landscapes of France, Scotland and Somerset, England, where McCullin was evacuated as a child during the Blitz and which he now calls home.

Rendered in his signature deep, dark tones, these painterly depictions of the English countryside – which McCullin has described as his greatest refuge – are worlds away from the battlefield but somehow echo his earlier work. On a windswept hill or in a flooded meadow in Batcombe Valley, McCullin has found his serenity, though it is a “desecrated serenity.” Just as McCullin is haunted by the destruction he has witnessed, so too are these calmer scenes. A sense of foreboding is never far away.

The same chromatic and emotional gravity carries over to a selection of still lifes inspired by the work of Flemish and Dutch Renaissance masters, as well as images of Roman statuary from McCullin’s “Southern Frontiers” series, his 25-year survey of the cultural and architectural remains of the Roman Empire. McCullin credits his late friend the author Bruce Chatwin with inspiring him to take on this mammoth project. With scant prior knowledge of the classical world (he suffered from acute dyslexia and left school at fifteen) McCullin decided to team up with Barnaby Rogerson of Eland Books and began photographing all the Roman cities along the north coast of Africa. It remains his proudest work.

McCullin is haunted by the destruction he has witnessed. A sense of foreboding is never far away.

For a man who has seen it all, McCullin is disarmingly modest, wary of the compliments and titles conferred upon him (a Commander of the British Empire in 1993, a knighthood in 2017). When we meet to discuss the exhibition, he recoils when I describe his images as iconic: “If you make a tragedy look too beautiful you’re not serving any purpose. I have a big moral question about my work. All these gongs, honorary degrees – in the end I don’t feel good because I shouldn’t be rewarded at the expense somebody else’s suffering. Those pictures in that room haven’t made the slightest difference to the world.”

But he will admit to one thing: a strong compositional eye. And he laments how nowadays people have largely stopped seeing the world around them, being glued to their phones. “My eyes have been the wealth of my mind and I’ve interpreted everything through them. It’s got nothing to do with photography. People say, “Oh, what camera do you use?” And I want to kick them up the backside! My photography is done purely emotionally. I’ve got good eyes; I can see things other people don’t see. They go about their lives looking at only one thing, their phone, so they’re missing the whole life around them. They think they’re getting information from their phone but it’s actually stealing their life away from them.”

McCullin’s story reads like a movie and, sure enough, there is a big Hollywood production in the works, with director Justin Kurzel in talks with Daniel Craig for the lead. But this also sits uneasily with the veteran photographer: “I feel slightly ashamed even thinking about it. If you celebrate your success it’s damaging. I’ve always done what I’ve done because I wanted my father’s name to be important. I’ve done my best to tread the path and behave myself because his name belongs to whatever I do. This has meant a lot to me because he didn’t have a very long life, you see. He died at forty when I was thirteen.”

Entering his ninth decade, McCullin shows no signs of slowing down. Three months ago, he was in Syria, visiting Palmyra for the fifth time. And he has just been invited to Antarctica to photograph the world’s largest icebergs: “I keep thinking about packing it in. I’m sick of going into my darkroom and standing in that lonely red light [McCullin does all his own printing]. And then someone comes along with the biggest carrot in the world and I’m like some old donkey who’s jumping in front of the others. I’m going to bloody Antarctica at 90.”

The exhibition is up for another two weeks. Do yourself a favor and go and see the work of this truly iconic photographer.

A Desecrated Serenity is on at Hauser & Wirth until November 11

Leave a Reply