What’s happened to the trade paperback? To my thinking, it provides the most pleasurable reading experience in the world. And yet it’s virtually disappeared.

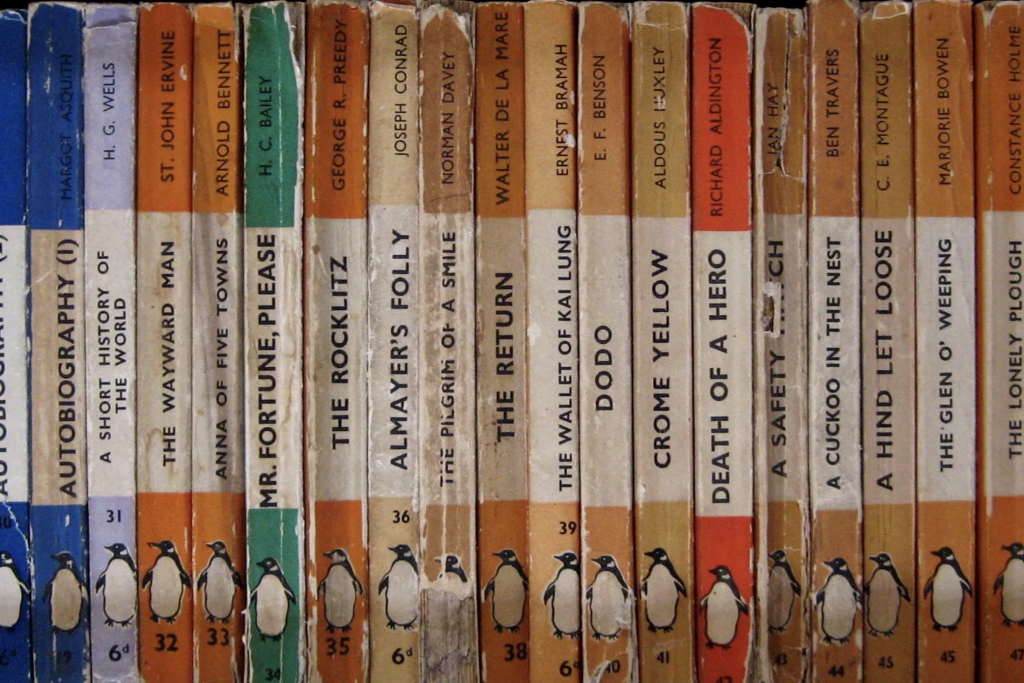

Trade paperbacks are the paperback versions that became ubiquitous during the latter half of the 20th century. They’re typically larger than mass market paperbacks and publishers print them on nicer paper. There’s also something amenable about the way a trade paperback’s covers give that makes for an optimal reading experience. It’s not like my world falls apart if I have to read a hardcover – which would surely happen if I ever had to read an ebook – but I can avoid a book for a long time if it means I’ll eventually wind up with the trade paperback version to read.

Hardbacks strike me as unforgiving. They don’t mold nicely to backpacks, coat pockets, or car door bins. The fact that these hardback editions are typically more expensive than paperbacks always seemed funny to me. They seem a punishment for wanting to read the book in the first place. I’ve never understood why anyone might want a hardback, save as a collector’s edition to sit unmolested on a bookshelf. In other words, less likely to be read.

I got used to waiting the typical year for a paperback version of a new release I wanted to read. Take my 2024 encounter with the hardback of James by Percival Everett. A look at the book’s blurb revealed it’s a retelling of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the point of view of Jim the slave. This struck me as a provocative new twist on a venerable story. I wanted to read it, but I noticed the book had just come out that year. I put it down and made a note to track down the paperback version as soon as it came out.

A quick calculation from James’s original publishing date revealed that the paperback version would come out in March 2025. When March rolled around, there was still no U.S. trade or mass market paperback of James for sale at my preferred seller. A quick pass at Amazon and Barnes and Noble revealed a large print paperback version for sale – which I guessed came out at the same time as the hardback edition – but no trade paperback.

March 2025 became April, became May. Still no U.S. non-large-print paperback of James. At this point, my writer friend Michael nudged me. “Dude,” he said. “Huck Finn told from the point of view of Jim.” Yeah, I’m in. To compound my interest, I was in the middle of writing my own retelling of a classic work, in my case the Iliad.

By July, with still no trade paperback version. The novel had won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in May, and from what I could gather, this meant that the hardback version had continued to sell well. Hardbacks generally sell for $8-$10 more than trade paperback editions. James’s publisher, Doubleday, clearly liked getting that extra bump for every non-ebook copy sold. At least, after a long delay, an explanation.

The ebook version must’ve played a role in this delay as well. With the advent of the ebook, publishers seem to have forsaken paperbacks for this new favorite cheap alternative to the hardcover. The only problem is, I’ve never read an ebook. Another screen? Sounds like work. My reading time is mine.

So, I was stuck with the hardback version of James. I bought it and read it and thought it was fine. I don’t want to say any more than that since this piece isn’t about the contents of James.

I do, however, want to say more about a corporate publishing world that refuses to acknowledge the beauty of the trade paperback. Beyond the edition’s clear utility, it’s the medium through which I have accrued a great deal of love for reading. Ever since college, when I fell for the novel form, the versions of Vonnegut and Orwell and Faulkner and Hemingway that won my heart were paperback versions.

I know I’m not alone in this. In his Esquire article “Why I Love Paperbacks,” Isaac Fitzgerald writes, “Paperbacks are light, and…foldable. If you forget one at the bar or by the swimming hole, you will not mourn, for the book will be found by somebody else.” The paperback says, read me, use me. It never pretends to be more important than the words themselves. Does the publishing industry want to abandon this perfect technology, which all but begs you to crack its spine?

And isn’t the literary world suffering something of a dearth of interest? The past few years have seen prominent publishers such as the New York Times, Esquire and The Nation feature pieces lamenting the lack of new, compelling literary voices. Few seem to doubt that folks by and large are less interested in the kinds of novels that win Pulitzer Prizes – the kind of novel James is. Now doesn’t seem the time to drag the readers of literary fiction away from the formats of new novels they prefer and force them to read in formats they don’t like. If you want to annoy your literary buyer, don’t worry, they’re already annoyed by a culture that’s abandoning them. Publishers exacerbate that annoyance by forcing them to read book editions they don’t want to read.

I understand that a giant publisher is always going to chase the last penny out of my pocket, but as the person giving up the pennies, I don’t want that to have to buy and read a hardback version of a new novel. I propose a solution: Release the paperback version of a new novel at the same time as the hardback version, and charge the same amount for both. Let’s finally get rid of the absurd waiting period for the paperback version to come out. Publishers can make more money charging trade paperback aficionados for their preferred version. Let us have your product in the way we want it at the outset, and charge us for it.

The increased price point shouldn’t much effect overall sales, or at least not profit. Any sales a publisher loses to people turned off by the price of a paperback version will, I suspect, easily be made up by that extra eight or ten dollars for each paperback sold to people like me. Record companies, after all, still make money off vinyl editions, the audio version of cooking over an open fire, or bathing in the river.

It’s an easy decision. People like me find the process of reading quasi-sacred. We want the words of published novels to transform us. Putting off – or forgoing entirely – the editions we most easily fall into makes this process harder for many devoted readers. Is that really what publishers want?

Leave a Reply