For many of Ukraine’s supporters, Donald Trump’s recent declaration that Ukraine “is in a position to fight and WIN all of Ukraine back in its original form” came as a welcome – and unexpected – turnaround in US policy. “Ukraine would be able to take back their Country in its original form and, who knows, maybe even go further than that!” wrote Trump in a Truth Social post in late September. “Putin and Russia are in BIG Economic trouble, and this is the time for Ukraine to act.”

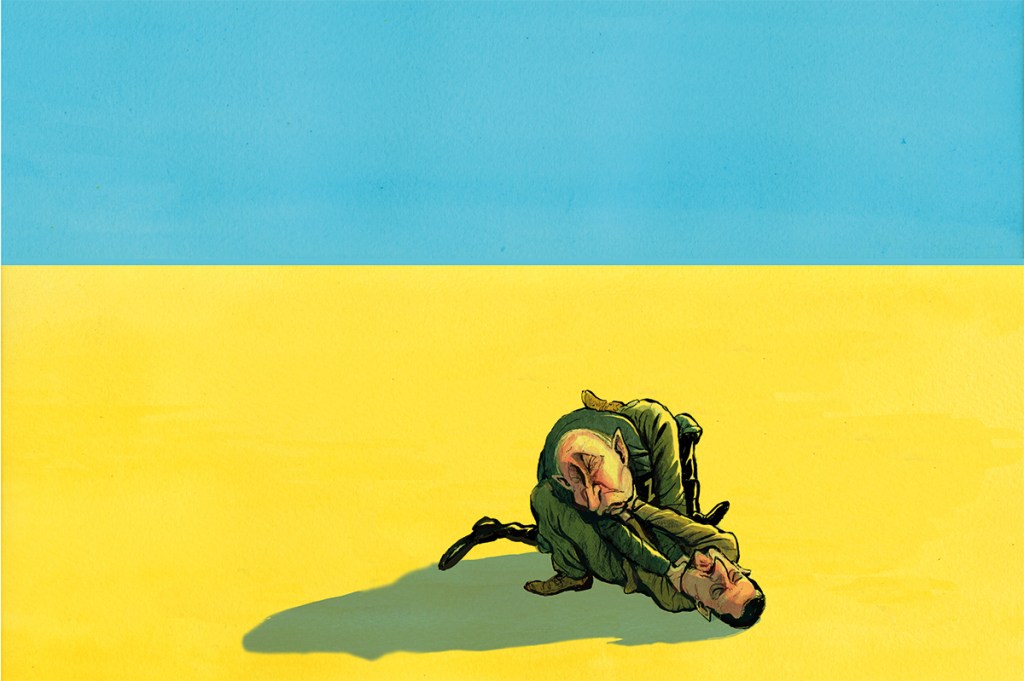

But would taking back the lost territories of the Donbas, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson and Crimea make Ukraine whole again – or could a reconquest instead condemn Ukraine to perpetual civil war against itself and prolong the conflict with Russia indefinitely?

The key challenge for Kyiv now, 11 years after much of the Donbas became essentially independent and three and a half years after Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion, is that de facto ethnic cleansing has happened on a massive scale. The pro-Ukraine, pro-Kyiv population left the occupied areas, the pro-Russian stayed. To those who remained and collaborated with the new Russian authorities, a Ukrainian reconquest would not be a liberation but an invasion. The single largest contingent in the Russian army has been made up of local men from the Donbas – 120,000 of them. To get the territory back, Kyiv would have to fight these veterans for their own home territory. Now that partition is a reality, how realistic is it that Kyiv could reverse it?

On the one hand, there is the argument that without Russian interference there would have been no civil war in Ukraine in the first place. While there were tensions between the Russian speakers of the Donbas and Crimea and the central Kyiv government before 2014, none were remotely serious enough to have sparked an armed insurrection. It was Russia that fanned the flames and turned local tensions into a regional war. Before Putin annexed the Crimean peninsula in February 2014, the one party that advocated separatism from Ukraine polled just 2 percent in local votes. In the aftermath of the Maidan uprising in 2014 Russian speakers in the Donbas were certainly resentful of laws imposing the Ukrainian language, over the ousting of the Donbas-based Party of the Regions and its leader Viktor Yanukovych and over a takeover of power in Kyiv by strongly pro-EU and anti-Russian Ukrainian nationalists.

But the Donbas’s armed insurrection against Ukraine was not a homegrown affair; it was deliberately started by an influx of armed Russian ultra-nationalists led by ex-Russian military intelligence officer Igor Girkin (aka. Strelkov) and covertly backed by the Kremlin and Russian security services. By Girkin’s own account, the decision to launch an armed uprising in the Donbas was his, not the Kremlin’s. “At first, nobody wanted to fight,” Girkin claimed to the ultranationalist Russian newspaper Zavtra. “I’m the one who pulled the trigger of war… our squad set the flywheel of war in motion. We reshuffled all the cards on the table.”

I traveled extensively in the Donbas in the spring and summer of 2014 and often heard a telling phrase from fighters on both sides of the front lines – the other side had “brought war to our land,” they said, which is why they had volunteered to fight to defend their land against “invaders.”

Sergei Fedorenko, a Donetsk University history student who had volunteered at the headquarters of the self-styled government of the Donetsk People’s Republic, told me that “Kyiv had had their uprising” but the Donbas rebellion was “our Maidan.” By the late summer of 2014, the Ukrainian army had launched a full-scale military offensive to crush the rebels – and Putin had covertly deployed regular Russian armor, artillery and troops which crushed Kyiv’s forces. Russia, from that point, was inextricably invested both militarily and politically in the future status of Eastern Ukraine.

Volodymyr Zelensky was elected President in a surprise landslide in May 2019, on the promise of bringing the low-intensity conflict in the Donbas to an end – and normalizing relations with Russia. By October 2019, Zelensky had struck a deal with the leadership of the rebel republics of Luhansk and Donetsk to hold a referendum on their future status. Importantly, there was no question at that time of the eastern republics joining Russia or becoming fully independent – and even the Kremlin was still insisting that they were part of Ukraine. But the referendum plan was scuppered by protests by Ukrainian ultranationalists in Kyiv, led by Azov Brigade founder Andriy Biletsky. The last peaceful chance to re-incorporate the Donbas into Ukraine was lost.

From 2014 onwards, a steady exodus of Donbas residents fled east into Russia and west into Ukraine. The economy of the once-prosperous region – Donetsk had even hosted the Euro 2012 soccer tournament – was ruined. Everyone young enough and smart enough to make a new life for themselves elsewhere left voluntarily, while many ordinary people whose homes along the front lines had been destroyed were forced to seek shelter with relatives and acquaintances wherever they could.

This exodus rose to a flood in the aftermath of Putin’s 2022 invasion, especially after Russian forces began systematically rounding up pro-Kyiv activists and anyone who had worked for Ukraine’s army or security services. The practical result was a massive political and ethnic cleansing. Those who remained in the Russian-occupied territories were forced to accept Russian passports, re-register their property in a Russian land registry or risk losing it and, most terrifyingly, faced the mobilization of their menfolk into the ragtag army of the Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics (LNR and DNR).

Could a reconquest condemn Ukraine to perpetual civil war and prolong the conflict with Russia indefinitely?

Far less disciplined than the regular Russian army, the Donbas levies sometimes fought with antique pre-World War Two rifles. They also suffered some of the highest casualties in the early months of the war.

One of the most striking things about the first phase of the invasion was how isolated the resistance to Russian troops was in the south of Ukraine. In the north of Ukraine, around Kyiv and Chernihiv, Putin’s Battle Group North encountered strong resistance – and meted out horrific retribution against civilians in Bucha, Irpin and other towns.

But in the south, Russian units from Crimea reached the Kakhovka dam just four hours after crossing the border and surrounded Kherson a day later. They encountered little resistance either from the Ukrainian army or from locals. In the center of Kherson, hundreds of citizens marched with Ukrainian flags, but the protests soon melted away after the brutal arrests of some of the ringleaders. Only Mariupol, the home of the ultranationalist Azov Battalion, held out and was systematically destroyed by massive Russian bombardment. Several dozen Russian-installed local administrators were assassinated, whether by local partisans or by Ukrainian commandos is not clear. But by September 2023, the areas under Russian control were sufficiently pacified for referendums to be held which, unsurprisingly, showed support for joining the Russian Federation comfortably over 90 percent.

Today, there is no public opinion polling nor a free press and very little independent reporting from the Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine. We see only occasional snapshots through a glass, darkly. Russian journalist Alexander Chernykh has recently reported from Donetsk for the Moscow-based Kommersant Daily and found locals resentful of water shortages, of Ukrainian bombing, of a lack of public transportation and basic services. “Many soldiers wear Soviet flags and insignia,” complained one Donetsk resident. “As if these people are fighting not for modern Russia, but for another state.”

Another anonymous local told the BBC Russian service that “occupied Donetsk is useless to anyone. Young people are waiting till they are old enough to leave to ‘free’ Ukraine.” What is hardest to find are voices, even on anonymous Telegram channels, from inside occupied Ukraine calling for a liberation.

Seen from Kyiv, the problem of regaining the lost territories is an impossible conundrum. On the one hand no government official or politician – not even the more pragmatic voices such as former foreign minister Vadym Prystaiko, former Zelensky advisor Oleksiy Arestovych or current presidential advisor Mykhailo Podolyak – dares to publicly acknowledge that the territories are lost forever and that reconquest is impossible. In private, however, several current and former members of the Zelensky administration say that Ukraine is a more united nation without the Donbas and Crimea.

“Why would we re-incorporate this bleeding wound back into our country?” one former official who was a senior member of Zelensky’s government asked me in Kyiv recently. “Our task is to build a country that is secure from Russian aggression and a place where our children have a future… [Russia] has destroyed the occupied territories, turned them into a wasteland. That is a tragedy. But our job is to look to the future, not cry about the past.”

In practical terms, too, a reconquest would involve a titanic and bloody military effort which a near-exhausted Ukrainian army could not, at present, conceivably undertake. Not to mention the catastrophic damage that the Russian invasion has wreaked on the region’s infrastructure, smashing key economic powerhouses such as the Azovstal steel works and dozens of deep coal mines which were once the region’s lifeblood.

And even if, by some miracle, Kyiv’s forces were to take the shattered region back, what to do with the thousands of Russians who have bought cheap property there or who have been moved into the region from poor areas of Russia? They would, presumably, have to be ethnically cleansed in their turn. And then there is the question of political representation. With the electors of the occupied territories back inside Ukraine, the electoral map would once again swing back toward pro-Russian parties like the one ousted by the Maidan revolution.

Restoring Ukraine’s prewar borders sounds, on the face of it, a just solution to an unjust invasion. But, as the Ukrainians say, a split trough cannot be made whole. In “liberating” much of the Russian-speaking part of Ukraine, Putin has smashed it and robbed its people of their futures – and in the case of thousands, their homes and lives. But at least the remaining 75 percent of Ukraine has a chance to rebuild and consolidate its democracy and statehood and one day become a prosperous European country. That will be its true victory.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply