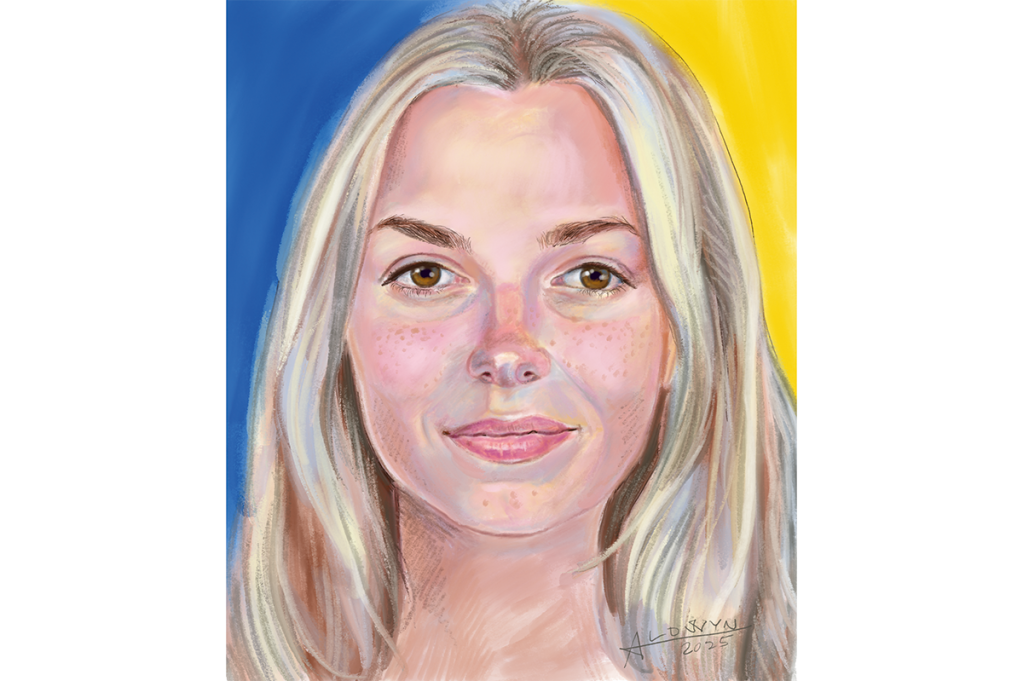

Decarlos Brown Jr. should never have been on the streets. The man suspected of murdering 23-year-old Iryna Zarutska, a Ukrainian refugee, in Charlotte, North Carolina, in August had been arrested 14 times in almost as many years, charged with armed robbery, shoplifting and property damage. According to his sister, he is a schizophrenic who suffers from paranoid delusions. But he was free to roam in part because of the race hustle.

Want to fire an employee? Good luck if that employee is black; such a dismissal would be presumptively racist

For decades, pointing out that any action, public or private, had a black target or fell disproportionately on black people was sufficient to discredit that action, regardless of whether it was couched in terms of race or had a racist intent.

Want to fire an employee? Good luck if that employee is black; such a dismissal would be presumptively racist. Tempted to criticize a government official for alleged incompetence or unethical conduct? If that official is black, think twice, since blackness is used as a shield. Try to jail a serial violent offender, such as Brown Jr., who happens to be African-American? That would contribute to racial inequity.

The idea that racial disparities in arrest and incarceration rates reflect discrimination and not disparities in criminal offending has been a staple of Democratic policymaking for years. The “systemic criminal justice bias” conceit has led district attorneys across the US to stop prosecuting and stop seeking jail terms for a host of crimes, simply because penalizing those crimes would have a disparate impact on black criminals.

North Carolina has embraced the disparate impact idea. In 2020, after the George Floyd race riots, then-governor Roy Cooper established the “Task Force for Racial Equity in Criminal Justice,” which pushed to eliminate racial disparities in charging decisions. It demanded racial-equity training for district attourneys, judges and parole officers and sought to educate prosecutors about “unconscious bias.” The Office of Equity and Inclusion in Mecklenburg County (where Charlotte is located) is dedicated to reducing racial disparities in the criminal justice system and has hired equity and inclusion consultants to help.

If white toddlers were gunned down at the rate black toddlers are, there would be a revolution

Charlotte’s police chief, Johnny Jennings, believes law enforcement is “based on racism.” In 2020, he announced an intention to “slow down” on discretionary arrests. It was overdetermined, then, that Zarutska’s future murderer would not be locked up. The system was no longer set up to hold him or anyone else who committed similar crimes.

Today, the race card is being furiously played against several of Donald Trump’s initiatives. On August 11, Trump declared a “liberation day” in Washington, DC: “I’m announcing a historic action to rescue our nation’s capitol from crime, bloodshed, bedlam and squalor and worse. This is liberation day in DC, and we’re going to take our capital back… we’re not going to let it happen anymore. We’re not going to lose our cities over this.” The President ordered a limited deployment of the National Guard to the Capitol and gave the head of the Drug Enforcement Administration oversight authority over the DC police force.

Democratic politicians, interest groups and the media immediately accused Trump of an illegal power-grab and insisted that there was no crime problem in Washington because crime there had dropped since the previous year. But it was still at a level that should be unacceptable in a civilized society. The DC homicide rate after that modest crime decline is 21 times that of London, for example, and almost 60 times that of Switzerland, a condition that might well be considered a national emergency. Those DC murders, as in other American cities, regularly include child victims, such as three-year-old Honesty Cheadle, who was caught in a drive-by shooting after a Fourth of July cookout this year, and Ty’ah Settles, also three, who was felled by a stray bullet from a drive-by shooting in May 2024.

Trump mused about taking his focus on crime to other cities, especially after the positive results from the federal deployment in DC started rolling in. He has mentioned Chicago, Los Angeles, Baltimore, Oakland and New York City as possible targets. The race hustle, already in play, leapt to the fore. Washington, DC, and the five other candidate cities all have black mayors, it was pointed out ominously. Some have large black populations. So Trump was motivated by racial animus and his crime initiative could not possibly be legitimate.

Trump had said nothing about race. It did not matter. On August 12, the Associated Press declared: “Trump’s DC rhetoric echoes a history of racist narratives about urban crime.” The AP invoked a favorite Democratic trope: that whenever a Republican official speaks about law and order, he is exploiting a nonexistent problem to win over racist white voters. The organization also said the deployment of the National Guard echoed “uncomfortable historical chapters when politicians used language to paint historically or predominantly black cities and neighborhoods with racist narratives to shape public opinion and justify aggressive police action.” The AP did not ask whether crime levels ever justify a promise to restore law and order; it assumed that they never do.

Amnesty International USA echoed the AP line. The federal initiative was the “latest expression of a longstanding racist narrative: that black and brown communities represent danger, disorder, and lawlessness and that only force can restore control. This problematic and untrue framing has deep historical roots in white supremacy and racist myth-making and its resurrection underlines how ‘public safety’ has often been weaponized against communities of color.”

Marc Morial, president of the National Urban League, told NBC News that Trump was “playing the worst game of racially divisive politics, and that’s all it is.” Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott complained that Trump was “spouting these racist-based, right-wing propaganda talking points about cities and black-led cities,” reported Politico. Trump had obeyed America’s etiquette on crime and had stayed silent about its demographic distribution. Yet since his opponents have introduced the subject of race, it is worth looking at the numbers that are ordinarily kept far offstage.

In Washington, DC, from 2019 to the end of 2020, black people made up nearly 97 percent of homicide suspects, according to the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform. White people accounted for 0.8 percent of homicide suspects. Black people are 46 percent of the DC population, white people 38 percent. The black homicide commission rate is roughly 99 times higher than the equivalent for white people. In Los Angeles in 2022, black people were more than 21 times as likely to be suspected of a violent crime as their white counterparts. They were nearly 37 times as likely to be the suspect in a robbery. Black New Yorkers were 46 times as likely to commit a shooting as white ones in 2023.

Even if a Democrat were to retake the White House, the racial juggernaut may be too difficult to reassemble

Data on the race of crime suspects is becoming harder and harder to obtain; at best, most departments provide only victim race data. But victim race is a decent proxy for suspect race, since, as the left likes to say (without understanding the implication), most crime is intraracial. (The predominance of intraracial crime does not mean that interracial crime is not also racially disproportionate. The Zarutska killing was typical. A black person is roughly 35 times as likely to commit an act of violence against a white person as the other way around, according to the National Academy of Sciences.)

From 2000 to 2019, nationally, black men between the ages of 15 and 24 died of homicide at a rate of 75 per 100,000, according to a study in JAMA Network Open. The white male homicide victimization rate in that age group was a little over four per 100,000, making the black homicide victimization rate 18 times greater.

A CDC study found that black people between the ages of ten and 24 died of gun homicide at nearly 25 times the rate of white people in that age cohort from 2020 to 2021. A JAMA Network Open research letter published in March 2023 found that black juveniles were shot at 100 times the rate of white juveniles in LA, New York, Chicago and Philadelphia in the post-George Floyd era.

Who is shooting and killing these black victims? Overwhelmingly, black perpetrators. Disparities in criminal victimization rates mirror disparities in criminal offending rates. That symmetry explains why Black Lives Matter activists are silent about the dozens of black people killed in homicides every day – more than all white and Hispanic homicide victims combined, though black people only make up 13 percent of the population. If the activists were to draw attention to the victims of that daily bloodshed, they would risk drawing attention to the perpetrators as well.

If white toddlers were gunned down at the rate that black toddlers are, there would be a revolution. But young black victims such as Honesty Cheadle are ignored by the national media and activists: her suspected killer was also black. No one – outside her family – says her name.

Racial disparities in criminal victimization mean that the police cannot go where people are most being terrorized by street crime without being disproportionately in black neighborhoods. The bodies do not lie. You can have data-driven law enforcement targeting crime or you can avoid disparate impact. You cannot have both.

So when Trump vows to tackle the urban crime problem, he will necessarily be directing federal attention to cities with significant black populations. That does not mean that he is targeting them because of their demographics or leadership.

Trump’s plans, announced in September, to send more federal resources to Memphis and New Orleans elicited the usual response. “Memphis, like most of the cities singled out for perceived leadership failings, is led by a black mayor and has other prominent black leaders in city government,” observed the New York Times. “The head of the police department is also black.” New Orleans Council member Lesli Harris said: “Sending troops into black and brown cities is not a solution.”

The race card is also being played with regards to Trump’s effort to fire Lisa Cook, who is described in headlines as the first black female governor on the Federal Reserve Board. The Guardian wrote: “The first Black woman to sit on Fed board faces another obstacle in a long line she has faced and written about.” NBC News added: “Cook weathered racist attacks as a child and became a pioneer as a black woman economist. Her latest fight is to keep her position on the board of governors at the Federal Reserve.” And Democracy Now! carried the headline: “First Black Fed Governor, Lisa Cook, Sues Trump over His Attempt to Fire Her.”

Trump’s indifference to being called a racist may be having a wider effect

Cook illustrates the asymmetry of the race card. Once someone is elevated to a position for race reasons, that person is protected from removal for non-race reasons. It was Cook’s identity as a black woman and her advocacy of black victimology that recommended her to Joe Biden in the first place, not any grounding in monetary economics or other policy areas in the Fed’s purview. Cook’s most circulated quote is her claim in a 2019 New York Times opinion piece that “if economics is hostile to women, it is especially antagonistic to black women.” In 2020, she called for the editor of the Journal of Political Economy to be fired for criticizing the “defund the police” movement. Her research on racial disparities has had replication problems and she has never provided full access to her data.

Yet her race helped her into a position on the Fed’s board. In 2022, then-Democratic senator Sherrod Brown claimed that Republicans should be “ashamed” to vote against her because “it’s been 109 years and seven people on the Federal Reserve at one time, and not one African-American woman ever.” Brown did not ask what the pool of competitively qualified female black economists has been over the last 109 years. The answer? Likely nonexistent. In 2022, there were 12 economics PhDs awarded to black women in the US. This constituted 0.8 percent of all economics PhDs awarded that year. But we are to believe that suitable female black economists have been regularly denied a seat on the Fed’s board due to racism.

The race defense is also active against Trump’s large-scale cuts to the federal bureaucracy. According to a front-page article in the New York Times, those cuts “disproportionately affect black employees – and black women in particular. Black women make up 12 percent of the federal workforce, nearly double their share of the labor force overall.” A Chicago Tribune columnist echoed the charge: “Trump and his MAGA supporters are happily targeting people of color, especially African-American women.”

Worse, according to the Times, “agencies where minorities and women were the majority of the workforce, such as the Department of Education and USAID, were targeted for the largest workforce reductions or complete elimination.” Never mind that those agencies were the most bloated, least effective and most politicized parts of the federal bureaucracy. Race ideology means that when an organization becomes disproportionately black, it becomes untouchable.

Never mind, too, that in light of the academic skills gap, such overrepresentation of minority women raises the possibility of a serious sacrifice of merit in favor of preferences. The average math score for a black pupil sitting the SAT in 2024 was 440 on an 800 point scale. The average math score for an Asian pupil was 629. Black pupils’ average total score on a scale of 1,600 was 907 last year, compared with the average of 1,024 for all test-takers (with 1,228 for Asian pupils and 1,083 for white pupils). The SATs measure language capacity and reasoning skills, still useful in government work, however debased such work has become.

The Times highlighted the higher-ranking black female managers whom Trump has removed, “often disparaging them as incompetent, corrupt or DEI hires.” But maybe they were at least some of those things. They were certainly committed to diversity ideology, whether believing in “white privilege” or “bringing an equity lens to [their] work” and that ideology is now being extirpated from the executive branch. Plenty of white male bureaucrats have been fired as well, but they do not have an identity defense available to them.

The race hustle has been one of the dominant forces in American society for decades. But is it finally losing its power? It has had zero effect on Trump. He continues to promise further federal deployments to high-crime cities. A few hours after Trump again criticized Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker’s failure to control crime in Chicago, the city’s gang members obligingly proved the President’s point with a drive-by rampage in Bronzeville (on Chicago’s South Side). Seven people were shot. That late August outburst was part of the usual violence that accompanies holiday weekends in urban America – in this case, Labor Day weekend. Bronzeville saw another mass shooting with five victims on Labor Day itself. All in all, nine people were killed and 52 wounded in Chicago’s South and West Sides over the three-day weekend.

Notwithstanding Mayor Scott’s earlier charges of racism, Trump has re-upped his threat to order federal resources to Baltimore. “We have an obligation to protect this country, and that includes Baltimore,” he said on September 2. Scott, ever-hopeful, played the race card again. “It seems they want chaos,” he said during a news conference. “It seems that they want certain images and certain types of people, especially people that look like me, to be easily depicted as violent or ‘born criminals,’ so to speak.”

Actually, Trump wants peace. He regards any murder as one too many. And he is going after crime where its toll is the most lethal. He cannot help the fact that 85 percent of Baltimore’s homicide victims from 2005 to 2017 were black men, while just 4 percent were white, reflecting an equal if not greater disparity in their assailants. (Baltimore’s population has historically been about 60 percent black and 30 percent white.)

Trump has not backed down from his efforts to remove federal bureaucrats and to extirpate federal agencies which he believes impede his agenda, regardless of the racial incidence of those cuts. Cook’s blackness did not scare him.

Trump’s indifference to being called a racist may be having a wider effect. Americans have played along for decades with the race hustle, terrified to be accused of bias or of insensitivity to the premier victim group. Now a collective fatigue may be setting in.

This latest round of racial critique seems to be falling flat and to be out of sync with the times. Maybe not everywhere and maybe not even now. But in four years, after the public has watched a President who is patently and shockingly indifferent to identity-based blackmail, arguments from skin color may be met with an eye roll.

Even if a Democrat were to retake the White House, the racial juggernaut may be too difficult to reassemble. Perhaps the universities, with their entrenched diversity infrastructure which is, at present, furiously camouflaging itself, will hold out. But everywhere else, the spell will be broken. If so, it will be one of Trump’s most transformative accomplishments.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply