Books of short stories are among the most difficult for writers to sell. Which is odd, as they’re often where the best writing is. A short story is rarely boring. It has to pack everything in, grip the reader right away, unfold its plot and make its point – a cultural truism or a subtle universal or a moral profundity – elegantly. It’s the one kind of writing I’ll always read when a friend says they’ve tried their hand at it.

Short fiction is lusciously versatile, from the fabulous supernatural tales of Dickens and Wilkie Collins or the potent tales of Kate Chopin or Stefan Zweig’s ominous 1941 novella Chess, to Miranda July’s gleefully genius compilation No One Belongs Here More Than You, to “Cat Person,” the New Yorker’s incredibly viral short story about a bad date, which was so successful it was made into a film of the same name. My only criticism of short stories is that they always end too soon.

Mull was a polymath in an industry that compartmentalizes people into pretty faces and the brains behind them

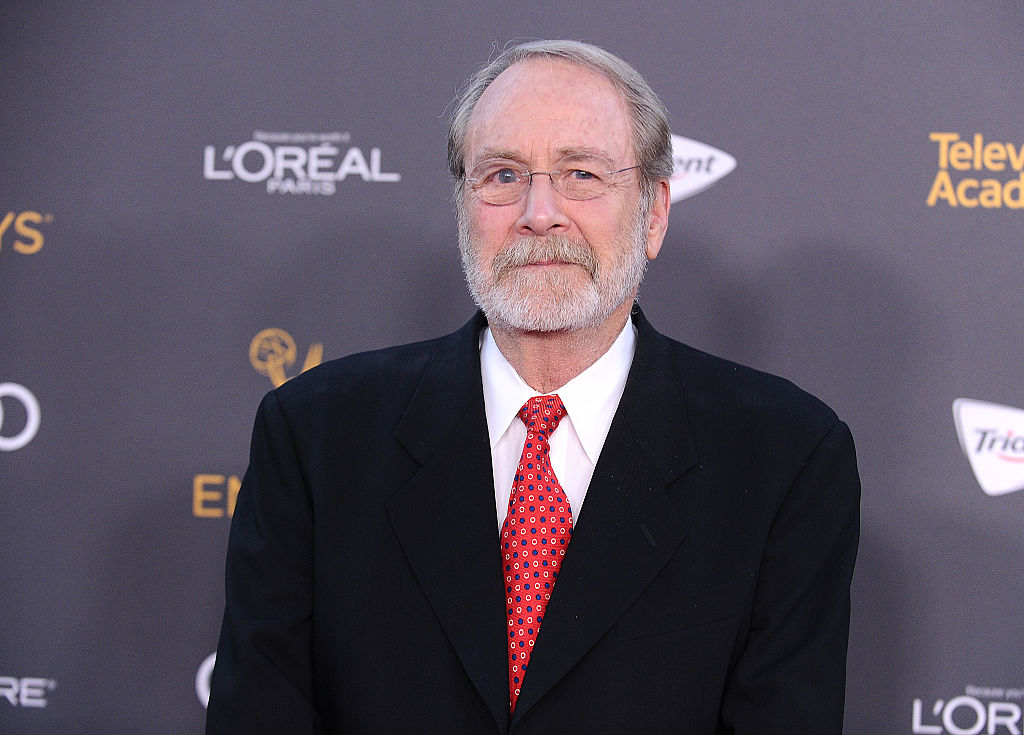

I felt the same reading the posthumous story collection of Martin Mull, who became a fixture on American screens over a long career that ended finally last year when, aged 80, he died after a long illness. Mull was a polymath in an industry that tends to compartmentalize people into pretty faces and the brains behind them. He wrote comedy and was a comic; he acted in film and TV from Mrs. Doubtfire to Arrested Development and Veep; wrote for shows such as The Tonight Show and Roseanne, and was a serious musician and painter. He could sing and he could write songs, opening for Randy Newman, Frank Zappa and Bruce Springsteen, while his waltzy album Sex and Violins was nominated for a Grammy in 1978. His 1985 mockumentary series The History of White People in America won the ACE award for best comedy special. And so on.

In Britain, where I live, Mull is not well-known and so I dove into Life Sentences relatively blind (I did appreciate him in Mrs. Doubtfire as a child). But then I read Eric Idle’s preface and suspected something good was on the way. “When people talk about the complete Renaissance Man,” Idle writes, “I always remind them that was Machiavelli. Martin had none of that Italian in him, he simply could do everything: paint, write, act, draw and play guitar, all wonderfully well. I miss him. But I’m grateful to have these stories to remind me what a clever bastard he was… What a man.”

Indeed. Had he done none of the other things, Life Sentences would still make Mull a fantastic artist. The stories here are about serious themes: ambition, hubris, the purism of the artist everywhere thwarted by business; friendship and aging – but they have a levity about them. Imagine a cross between Richard Yates, Tolstoy, Ottessa Moshfegh and your favorite culture writer. The stories riff on things Mull has seen and thought about during his long and interesting life, and they have the lightness of fiction and the silken maneuverability of perspective that only comes from hefty, hard-won skill, intelligence and natural talent.

Life Sentences has a commanding narrative voice, whichever man (all the stories are written from the perspectives of men) is narrating. I ended up savoring “Second Team,” about two Brown graduates who move to Los Angeles, one with acting ambitions, called Henry, and one who sees himself as a serious writer.

The latter, a man named Andy, is the narrator. “The writing I did for television couldn’t be further from the prose that manhandled my consciousness so many years ago when I was a flaxen-haired sophomore wandering the quad at Brown University,” says Andy, before telling us how he wound up accruing miserable wealth through the artistic bankruptcy of sitcom writing, and reflecting on life from a sprawling ranch in Montana.

There are welcome, light-touch nods throughout Life Sentences which acknowledge that it’s not just money – and capitalism’s agenda – which corrupt art, it’s wokeness. Andy explains that the Oscar Henry was nominated for was presented instead to “an actor in a Korean action film. It seems that every year the Oscars have an unspoken theme – a tacitly understood agreement that the awards should all go to some group that has been short-sold in the past; Henry’s year, unfortunately for Henry, was ‘Hats off to Asia.’”

My favorite of all, though, is “Life Drawing,” the sad tale of an art teacher who works to paint, sequestered alone for hours and days when possible in his garage – only for a chance encounter with a windshield-cleaning panhandler at a traffic light to lead to his golden period.

I liked the bittersweet endings mixed through even the tales of bodily decay and the way Mull treats being a thinking human adult trapped in a body breaking down in old age with a mixture of droll and brutal realism and wit. One leaves these stories not depressed, or full of the dread of death, but wanting to punch the air in solidarity with these ornery old dudes, who aren’t going down yet, or at least not without a fight. It turns out, though all Mull’s heroes are loners, other people are a necessary part of life.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply