It would be impossible for me to review Katie Herzog’s Drink Your Way Sober without disclosing the central fact of my adult life: I have been sober and in Alcoholics Anonymous for more than 15 years. And while I am not an out-and-out evangelist for AA and its notorious Twelve Step method, it is, nonetheless, the movement that I credit with my survival. Not so for journalist – and addict – Katie Herzog.

Herzog has all the serial-relapser energy you would expect from the addict who has forsworn AA

Part memoir, part guidebook, Drink Your Way Sober is an impassioned – and at times, angry – argument that abstinence-based approaches to sobriety are doomed to fail. Instead, Herzog asks us to consider medication-assisted treatment for addiction, specifically naltrexone, a drug that allows you to drink until you reach what its practitioners term “extinction,” or the loss of desire to drink at all. Apparently, it’s very simple; it’s also guided by science, not the mumbo-jumbo trust in self-help and finding community in church basements. The reason we don’t know about it is, Herzog argues, because the recovery industry doesn’t want us to know about it. In short, she says, we have a conspiracy on our hands.

Herzog comes at her readers with all the jaded, serial-relapser energy that you would expect from an addict who has forsworn AA. “I know how this sounds. It’s like I’m claiming you can cure diabetes with donuts. But it’s not crazy.” Thus we begin our journey with Herzog as she details the classic arc of any addiction narrative: the seedy details of her drinking, the lying, the metastasizing web of lovers and family pulled into the drama of addiction.

Some of this is compelling, if unoriginal. There is the childhood teddy bear lying face down in the dirt among her possessions thrown out of the window by an angry lover, “like a scene in a bad rom-com or a good reality TV show.” There is the economic collision of addiction with the world of work and the endless failed jobs and squandered chances: in Herzog’s case, the gig economy of journalism.

Then, naturally, there is the reckoning with societal perception of addiction, a trope now so well-worn as to be clichéd: “I wasn’t an alcoholic! I just liked to party! Alcoholics live under bridges. They’re men.” So far, so normal. Except Herzog doesn’t get her happy ending. Or not through Alcoholics Anonymous, at any rate. And this is where the book gets interesting even if its formulaic structure doesn’t allow for many surprises; you’ll have to wade through a long, turgid history of AA and its origins in the scorched earth of Prohibition America before you get there.

Eventually, Herzog details reasons why the medication-assisted treatment pioneered by scientist John D. Sinclair and his eponymous “Sinclair Method” has failed to catch on. The Minnesota Model, embraced by US rehab giant the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation and underwritten by the belief in a shift “from a life of isolation to a life of dialogue” has the monopoly both financially and culturally, with more than half a billion dollars in assets, a publishing house and a graduate school.

The cultural hegemony of Big Rehab, Herzog argues, is a disaster. Not just for the millions of addicts who can’t afford the prohibitive expense of rehab (anywhere from $5,000 to $40,000 a month) but, perhaps more crucially, for our understanding of alcohol use disorder as a condition that might in fact not be best understood in the framework of the holy trinity of the classic addiction narrative: childhood trauma, genetic predisposition and pre-engineered societal conditions. “What if we don’t all have underlying issues or trauma that made us drink in the first place? What if some of us drink simply because we’re drunks?” Herzog asks searchingly and achingly. What if there is “no reason to believe this is universal,” she dares. As a less than ideal reader, someone she might consider brainwashed by the very narrative monoliths she is trying to dismantle, I must admit that I am torn. What if, indeed?

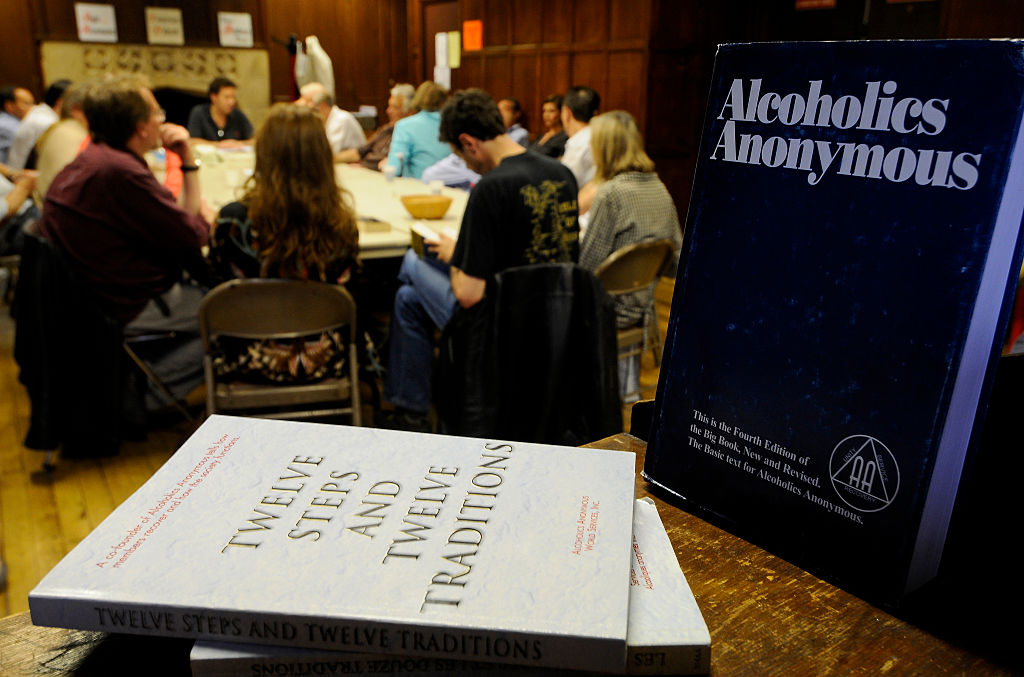

Herzog ends Drink Your Way Sober in an AA meeting, of all places. Why? She has, she explains, achieved almost a year of sobriety using naltrexone; she has a healthy marriage and a resurrected career. She has quit drinking by continuing to drink. The counterintuitive has triumphed. And yet. She has failed to tell her wife that her abstinence has been achieved through medication because of “shame, guilt, embarrassment.” Only the sacred communion of a roomful of other addicts can help: of this she is certain. The jumbled networks of other desperate souls discussing naltrexone on Reddit forums and underground messaging groups bring no relief, even as the drug may end the frantic search for abstinence in a cheaper, faster way.

I can’t help but conclude that Herzog ends her plea for medication-assisted recovery by kicking the ball into the wrong goal. But then again, maybe I would say that.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply