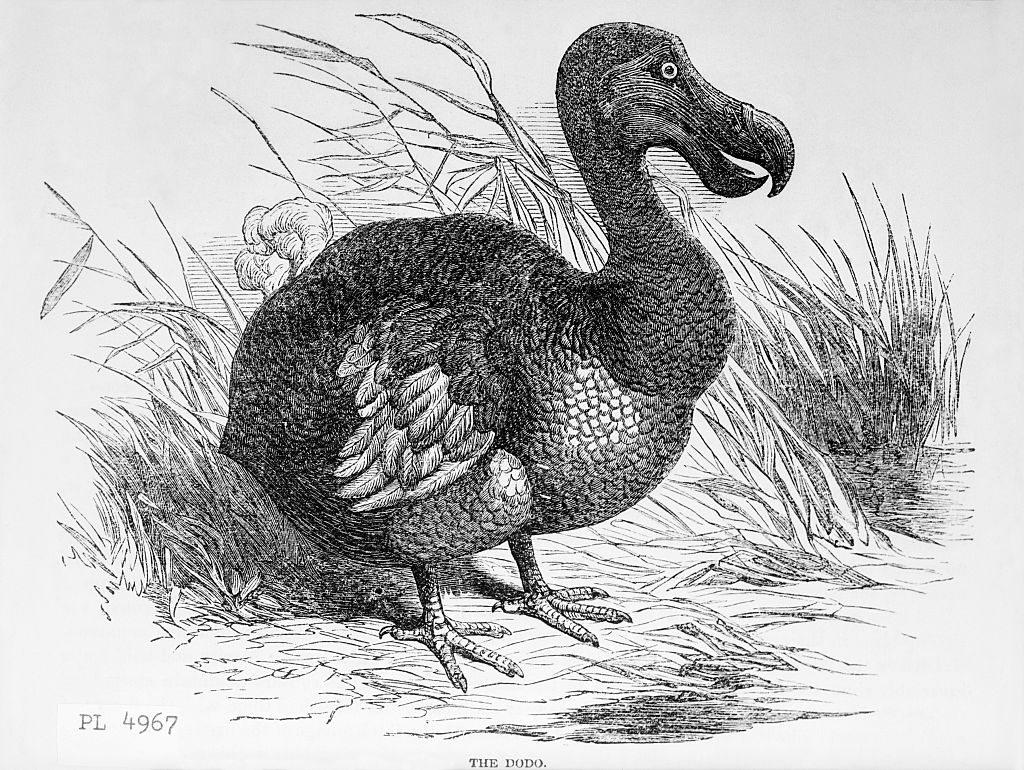

Colossal, a $10 billion biotech firm with a knack of grabbing headlines, has announced it is on the way to de-extinguishing the dodo, the very icon of extinction. Like most of Colossal’s announcements, this one included a hefty helping of hype. All the firm’s scientists have actually done on this occasion is prove they can grow primordial germ cells of pigeons, one of many necessary steps – and not the hardest one – in reviving the fat and flightless bird of the pigeon family of Mauritius that was the dodo.

In a couple of years, Ben Lamm, who runs the company, will probably present us with a fat and flightless pigeon with a funny beak and say: “Look, a dodo!” That’s roughly what he did last year when he made a big white wolf with just 20 genetic edits, which looked a bit like the dire wolf, an extinct species – and claimed that’s what it was. Hmm.

I have no connection with Colossal but I am an adviser to Revive & Restore, the non-profit organisation that started the de–extinction movement. Some in the organization are dismayed by the way Colossal raises expectations unrealistically.

Other extinct birds are even closer to coming back. The passenger pigeon genome has been sequenced. Ten years ago, I convened a meeting in Newcastle in England to discuss the possible de-extinction of the great auk, which is – remarkably – the only European-breeding bird species to have gone globally extinct in 500 years. The size of a penguin, it was a flightless cousin of the razorbill, driven to extinction by the 1840s as a result of its feathers being used to stuff pillows.

As we planned our meeting, we thought we would need to begin by debating how to find a way to read the great auk genome, but Tom Gilbert, director of the University of Copenhagen’s Center for Evolutionary Hologenomics, arrived to tell us he had already more or less done that, from cells in great auk guts preserved in alcohol in a Danish museum. Later he began work on a well-preserved dodo that was brought alive to Holland in the 1600s, preserved at Gottorf Castle in Germany and captured by Danish forces in 1702. This specimen was then passed to Colossal, and the deciphering of its genome sequence began.

We also thought we would need to find a way to foster great auk primordial germ cells inside the ovaries and testes of a surrogate species of bird – but Mike McGrew, a group leader at the Roslin Institute, arrived from Scotland to tell us he had developed a way to replace embryonic duck germ cells with chicken germ cells, so ducks could father chickens. In short, two of the hardest jobs were already nearly solved.

Many ecologists hate the idea of de-extinction and grasp at any argument to denounce it

That left two more hurdles: how to edit a razorbill genome into a great auk genome; and how to raise great auk chicks and release them into the Atlantic Ocean without parents to guide them. The first problem requires maybe up to a million precise spelling edits to a billion-letter genome. Gene-editing technology has made rapid advances in accuracy and volume since then but it’s a long way off achieving something on that scale. Still, you would not bet against it getting there in the next decade, perhaps through a series of semi-great auks.

As for the second problem, we find ways to raise and release red kites, white storks and sea eagles, so why not great auks? There are plenty of mackerel to feed them, and islands off Britain, Iceland and Newfoundland on which to release them into holding pens and then the open sea. I think there is every chance it will be doable in the next 20 years.

But that does not mean it will happen. There is a fifth hurdle that will have to be cleared: human negativity. Many ecologists hate the idea of de-extinction and grasp at any argument to denounce it – one reason Colossal’s hype is unhelpful. There is a reason the great auk went extinct, they say fatalistically: it probably could not survive in the North Atlantic now. But the reason was that we killed them to stuff pillows; if we choose not to do that, they should thrive as other auks – puffins, guillemots and razorbills – do today.

The critics also say that if we de-extinguish extinct species, people will stop trying to save endangered ones. Really? Think it through: those of us battling to keep curlews on the Pennine moors because we like their song are hardly likely to shrug and say let’s let them go extinct and then spend millions struggling to bring them back later.

The dodo announcement brought this sniffy response from an Oxford University biologist, Richard Grenyer: “It’s a huge moral hazard; a massive enabler for the activities that cause species to go extinct in the first place – habitat destruction, mass killing and anthropogenic climate change.” But climate change opens up feeding grounds slightly further north than where great auks lived in the 1800s. Anyway, says Andrew Torrance of the University of Kansas, reviving an extinct species is like mending something you broke – a moral imperative.

This is when the penny dropped. I suddenly realized what we are dealing with here: a philosophy that is all too common in the environmental movement, namely that being pessimistic about a problem is so lucrative that they hate solutions, or what they call technical fixes. I recently interviewed a brilliant Dutch entrepreneur of Croatian descent, Boyan Slat. Shocked at the plastic he met with when scuba diving, he set out to solve the problem – rather than just wail about it.

He founded Ocean Cleanup, a non-profit that has developed ways to catch and dispose of vast quantities of plastic in rivers and the sea. It is proving spectacularly successful, but he is baffled by the resistance he meets in the environmental movement. It is as if plastic in the ocean is not something they want to remove; it’s something they want to use to raise money. “Technology is the most potent agent of change,” he wrote a few years ago. “It is an amplifier of our human capabilities.” Yet for many greens, technology is the enemy.

I also met Michael Stephen, a British entrepreneur who developed a simple ingredient to add to plastic during its manufacture that turns it into a biodegradable substance. Exposed to heat or sunlight, this “oxobiodegradable” plastic decomposes and turns into food for bacteria. But Stephen finds himself stuck between a plastic industry that does not want to change and an environmental movement that wants to ban plastic: neither likes the idea of continuing to use and manage plastic but have it rot naturally if it is littered.

Once you see this mentality of preferring the problem to the solution, you notice it is everywhere. Nuclear power might solve climate change. Can’t have that – emoting about it is far too lucrative! Fertilizing the ocean might reduce carbon dioxide levels – therefore let’s not even try it.

Bringing back the dodo, great auk or passenger pigeon would be the ultimate technical fix and will therefore meet opposition. And it’s not just about birds. As for mammals, Andrew Pask at Melbourne University has sequenced the genome of the thylacine, an extinct marsupial predator known as the Tasmanian tiger. Then there’s mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply