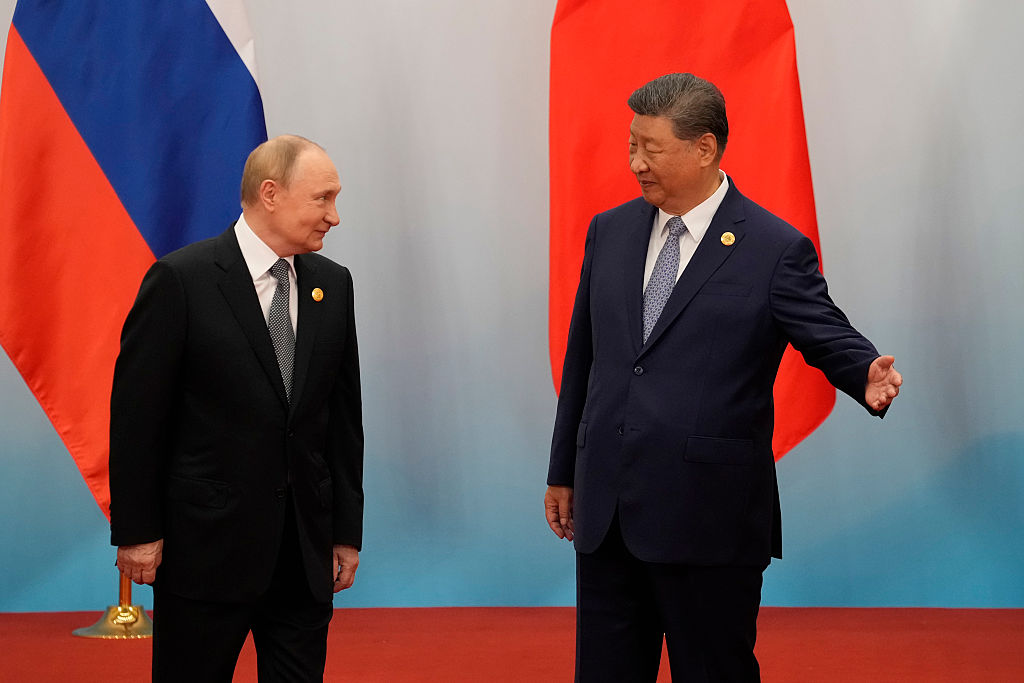

This summer’s big security summit in Tianjin, followed by the military parade in Beijing on September 3, has been widely interpreted as a sign of a new global realignment. At a time of growing friction within the US alliances in East Asia and Europe, President Xi Jinping of China, President Vladimir Putin of Russia and about 20 leaders mostly from Central Asia have not just reaffirmed their nations’ close ties. They sought to strengthen the emerging multipolar system, which they see as a rejection of the US-dominated global order.

This idea is hardly new. Three decades ago – when the bipolar Cold War gave way to what the neoconservative pundit Charles Krauthammer called the “unipolar moment” – the then-leaders of China and Russia pledged to work together to limit American power and influence in the world.

When Boris Yeltsin visited Beijing in April 1996, the rhetoric on both the Russian and Chinese sides was extraordinarily blunt. The joint communiqué of that visit, signed by Yeltsin and Jiang Zemin, all but branded America a threat to international peace: “The world is far from being tranquil. Hegemonism, power politics and repeated imposition of pressures on other countries have continued to occur. Bloc politics has taken up new manifestations.” A year later, during a five-day summit in Moscow in April 1997, Yeltsin and Jiang signed a “Joint Declaration on the Multipolar World and a New World Order,” which stated: “No country should seek hegemony, practice power politics, or monopolize international affairs.” It was clearly alluding to US predominance in global affairs. Citing the end of the Cold War, the declaration called for promotion of “multipolarization of the world and establishment of a new international order.”

Once bitter rivals, Moscow and Beijing were united by their fear of Washington’s interference in their domestic politics for purposes of promoting democracy as well as its plans to expand NATO toward Russia’s borders and reaffirm its alliance system across East Asia. These developments reflected the belief in Washington that, having just won a great victory which left the US as the sole great power on the planet, America should exploit its primacy to shape the world in its own interests. “Some are pushing toward a world with one center,” Yeltsin said. “We want the world to be multipolar, to have several focal points. These will form the basis for a new world order.”

Former US cabinet secretary James R. Schlesinger caught the significance of the prevailing mood in 1997 when he cited “the historic tendency” of rival powers – in this case, China and Russia – to “cut a leader down to size.” The logic was clear: if a great power tries to achieve global hegemony, other states will feel threatened and combine against it. Intriguingly, Washington at the time welcomed the growing closeness between China and Russia. President Bill Clinton described the development as “positive,” saying: “I don’t think we should approach these things with paranoia.”

There are limits to even US power, especially when Washington spends more servicing its debt than on defense

From today’s perspective, such remarks appear Pollyannaish. Back in the 1990s, however, neither Russia nor China was able to challenge American military supremacy because Russia, which succeeded the mighty Soviet Union, was militarily weak relative to the United States – as was China. Given American dominance, neither Moscow nor Beijing could afford to alienate Washington, especially since they were both increasingly dependent on western trade and investment. These were the salad days of America’s “unipolar moment.”

But it was just a moment. Before the 1990s were over, challengers began to appear. Moscow began moving toward Beijing after Russia’s honeymoon with the West ended over the decision to expand NATO eastwards, which united Moscow’s diverse political factions unlike any other issue. Even Western Europe, resentful of its dependence on Uncle Sam during the 45 years of Cold War, set out to make itself an equal of the US. For instance, when fighting broke out in Yugoslavia in 1991, Jacques Delors, then president of the European Commission, declared: “We do not interfere in American affairs. We hope they will have enough respect not to interfere in ours.” A few years later, after Europe had failed to end the wars in the Balkans, Brussels called on the US to intervene and stop the fighting.

Three decades later, Europe remains disturbingly dependent on the US for security, but the efforts of Russia and China to create a more multipolar world have succeeded and have altered America’s position in the global balance of power. Although Russia is the weakest of the three great powers, it has made clear with its brutal invasion of Ukraine that it will not tolerate a western bulwark on its border.

China, on the other hand, is a rising great power that is determined to challenge US preeminence. By converting its economic power into miliary might, Beijing is increasingly imposing its influence across East Asia to ensure its future security. For the Chinese Communist party, a sphere of influence is a badge of great-power status. Meanwhile, the Trump administration’s doubling of tariffs on Indian goods to 50 percent appears to have driven New Delhi into the arms of the Chinese.

But for all the talk of a new global realignment in Beijing, there is a danger in overstating. The US remains the most powerful economic and military power whereas China and Russia have their fair share of serious problems. Moreover, both still have reasons to forge closer relations with Washington. Moscow wants to end crippling sanctions while Beijing seeks a reduction of US tariffs. Nonetheless, the days of unipolarity, where the US could maintain a large military footprint in almost every region of the world, are long gone. There are limits to even US power, especially when Washington spends more servicing its debt than on defense.

In a multipolar world, it makes strategic sense for the US to place less emphasis on Europe and the Middle East and instead fully pivot toward East Asia. Keeping China’s regional ambitions in check is in America’s national interest. The US cannot afford to be the global policeman, but it can and should be heavily engaged in the region that is of the greatest strategic importance: East Asia.

Read David Whitehouse on the coming space wars in this issue.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 15, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply