Fresh on the heels of news that the government will take a 10 percent stake in failing chip company Intel, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick has floated the possibility of commanding a direct stake in Lockheed Martin and other large defense corporations. Speaking on CNBC, and extolling the “exquisite” proficiency of Lockheed products, he claimed “my Secretary of Defense and Deputy Secretary of Defense are thinking about it.”

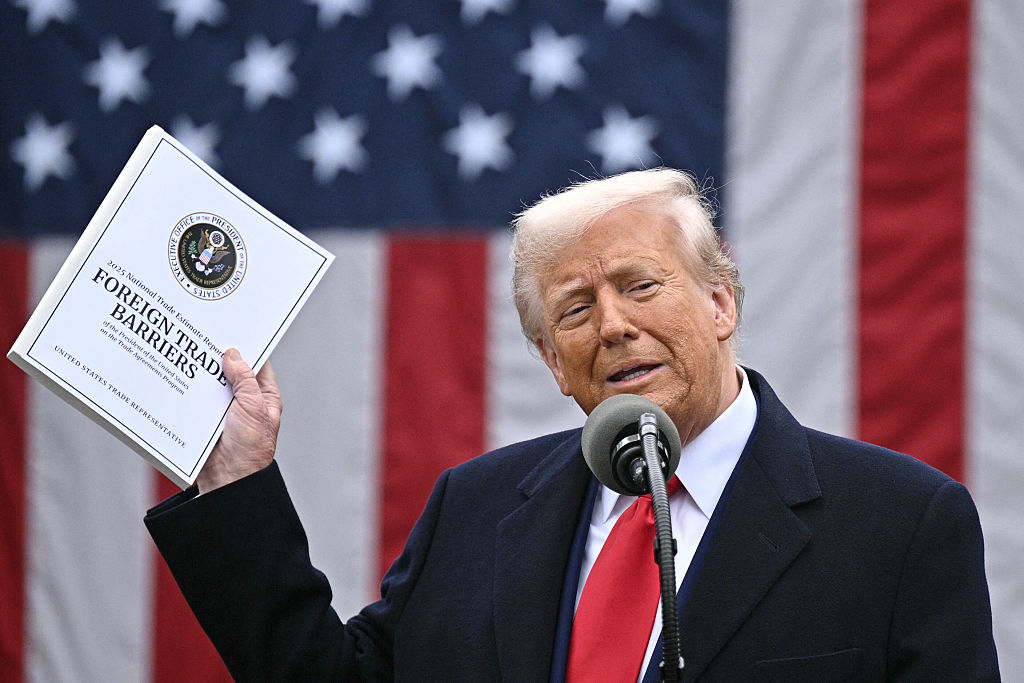

The proposal obviously fulfills a key requirement, which is to appeal to the transactional proclivities of the boss. Donald Trump had greeted the Intel arrangement as a “good deal” criticized only by “stupid people,” and suggested that there will be more such investments. (As is already happening with the injection of Pentagon funds into rare-earth producer MP Materials.)

The Intel deal at least involved no further investment of taxpayers’ cash, since it involved merely the conversion of Biden-era CHIPS Act bailout money into a stock holding. But it is hard to discern merit in turning weapons production into more of a government-run enterprise. The prospect has certainly excited alarm among free-market partisans. “I don’t really understand why they would want to do this,” Todd Harrison, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, told Defense News. “This is basically abandoning the free market for national security. This becomes state capitalism, much more in the model of China than in the American tradition.”

But Harrison and other such complainers miss the point. The free market in national security went away a long time ago; major defense firms already enjoy a symbiotic relationship with Uncle Sam. As Lutnick himself told CNBC, “Lockheed is basically an arm of the US government” deriving 97 percent of its income from government contracts. Much the same applies to the rest of the defense-industrial sector, with sellers and the buyer enjoying a seamless relationship in which a perpetually revolving door spins defense officials into the corporate world, including as lobbyists, and back.

Close examination indicates that in the US, one branch of the bureaucracy buys weapons from another

A 2023 report by Senator Elizabeth Warren detailed how the top American defense contractors employed no fewer than 672 former officials, military officers, along with former members of Congress and staffers as board members, lobbyists and senior executives, with Boeing leading the way. A total nationalization of the defense industry could potentially eliminate the current army of lobbyists. Yet, as one longtime critic put it, “I’m not crazy about replacing private sector lobbyists with government official lobbyists. With even more politicians having a finger in the pie, what could possibly go wrong?”

Though Lutnick would hardly care for the comparison, our system has broad similarities with the way the Soviets ran defense, a system replete with bloated and inefficient enterprises staffed by an army of dependent bureaucrats and workers insulated from competition or failure. It ultimately bankrupted the Soviet economy.

Close examination indicates that in the US, one branch of the bureaucracy buys weapons from another branch. This arrangement does not allow for failure, since those who lose out in bidding for a particular contract can customarily be assured that they will be compensated next time around. Thus Boeing lost to Lockheed in the competition for the lightweight fighter contract that spawned the ill-famed F-35. But now it is Boeing’s turn as winner of the contract for the next multi-billion US Air Force fighter contract, the F-47. Sometimes the process is short-circuited, as in the case of the Navy’s littoral combat ship (LCS), for which Lockheed and General Dynamics submitted competing designs. Under pressure from the contractors’ congressional offshoot, the Navy bought both rather than picking a winner. The program was beset by gigantic overruns in cost and produced a fleet of ships prone to breakdown and equipped with deficient weapons systems.

The problem is exacerbated by the domination of our defense industry by an oligopoly of five “prime” contractors – Lockheed Martin, RTX (formerly Raytheon), Boeing, General Dynamics and Northrop-Grumman. In its present form, the oligopoly was fostered by Clinton’s defense secretary William J. Perry. Following the end of the Cold War, he thought it a fine idea for these corporations to absorb multiple weapons producers – at least 40 at the time – on promises of efficiency and cost-savings.

The mergers Perry promoted were lubricated with attractive tranches of government cash. As the sorry saga of the Lockheed-General Dynamics LCS program ($100 billion lifetime cost), not to mention the US Army’s Future Combat Systems program supervised by General Dynamics ($20 billion, but nothing actually produced) or the Air Force and Navy’s F-35 deal with Lockheed (years late, multiple shortfalls and a doubled cost) might indicate, these promises remain unfulfilled.

Meanwhile, unlike the hapless Intel corporation, which lost almost $19 billion last year, the surviving defense giants are extremely profitable. In 2024, Northrop, for example, had an overall operating profit of just over 10 percent; Lockheed, though doing less well than in recent years, still turned in a profit of just over 7 percent, with chief executive James Taiclet taking home more than $23.8 million in total compensation. Even Boeing, hobbled by spectacularly inept management in recent decades, is back to making money on its defense business.

Pentagon shortcomings have attracted vehement criticism of late, and there is the threat of competition from the burgeoning tech industry centered in Silicon Valley, where companies large and small are eager to get a slice of the $1 trillion defense budget. The software company Palantir, for example, was founded by entrepreneur Peter Thiel with the express intention, according to his biographer, of bringing “the military-industrial complex back to Silicon Valley, with his own companies at its very center.”

Last year, Shyam Sankar, Palantir’s chief technology officer, penned “The Defense Reformation,” a trenchant critique of current defense procurement practices, complete with an excoriation of Perry’s rearrangement which, he wrote, had led to a “monopsony” in which “one entity is the sole buyer of a given product or service,” thus stifling innovation. Highlighting the need for competition, Sankar called for an overhaul of the way the Pentagon does business and demanded the deployment of artificial intelligence (central to Palantir’s business) across the board.

Pentagon shortcomings have attracted the threat of competition from the burgeoning tech industry

Yet there are telling signs that the disruptors of Silicon Valley will not bring about significant change to business as usual. The company’s roster is already festooned with a host of former Pentagon officials and politicians, including former congressman and noted China hawk Mike Gallagher, heading its defense business. Meanwhile, Palantir’s sister company Anduril is set to garner a contract enjoined by the “Big, Beautiful Bill” that has been carefully crafted to benefit the Thiel-founded firm – and none other. Buried deep in the bill is a section authorizing border surveillance towers that specifically requires they be “autonomous,” i.e., controlled by AI, a technology for which the company is the sole vendor, thus granting Anduril a profitable monopoly.

Partisans for further government support and control of the defense business may point to China, where major defense firms are government-owned, as a worthy example of the benefits of such a system. The expanding Chinese military, supplied by giant government-owned firms such as Norinco and Avic, do indeed get glowing reviews on this side of the Pacific, not least from tech industry hawks such as Gallagher and Anduril president Christian Brose. But since China has not fought a war since 1979, we know very little about its actual military abilities. Xi Jinping feels the need regularly to purge his military high command on grounds of corruption, notably including the People’s Liberation Army’s Equipment Development Department, which is responsible for developing weapons and widely cited as a hotbed of graft. The actual performance of Chinese weapons systems is a matter of conjecture and hype. There have been complaints out of Pakistan, a major customer for Chinese hardware, about reliability, including in frigate warships, although the recent Pakistani success in downing French-supplied Indian Rafales with their Chinese J-10 fighters (reportedly thanks to longer-ranged air-to-air missiles) was a significant publicity boost.

DJI, a privately owned Chinese company, is by far the most successful drone company in the world and has done thumping business supplying both sides in the Ukraine war. Its DJI Mavic 3 drone ($3,500 on Amazon), when suitably adapted, is held in high esteem by Ukrainian and Russian soldiers alike and remains in demand more than three years into the war. Other recent reports out of Ukraine reference a formidable attack drone recently deployed by the Russians, dubbed the V2U by Kyiv. That machine carries an AI chip, the Jetson AGX Orin processor, made by none other than US chip powerhouse Nvidia. That’s private enterprise at work. So, for a real payoff, Lutnick and “his” defense secretary might consider putting more money into Nvidia – or even DJI.

Andrew Cockburn is Washington editor of Harper’s Magazine. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 15, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply