My name is Curtis. I’m a GenXer. I love Wes Anderson. I also like IPAs. Sometimes it’s OK to be a cliché. The Phoenician Scheme is not Wes Anderson’s best movie (that would be The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou), or even his second-best. It may be his most transparent, though.

Wes Anderson is certainly our auteuriest of major auteurs. A Wes Anderson film knows it’s a Wes Anderson film and doesn’t mind that at all. As a monarchist, I always point to auteur theory as a micro-reflection of my crackpot political theories. If it were possible for corporations to make movies by committee, it would certainly be done that way. But it isn’t.

Instead, even the most hackneyed superhero sequel has a director – just as even the cheapest taquería has a chef. It is only a short step from these small present realities to Burckhardt’s concept of the Italian Renaissance, “the State as a work of art.” So every director is a working king. Some kings just read the king manual and try to follow it. In Hollywood, the Italian Renaissance, Silicon Valley, or anywhere else, the king business is competitive, that won’t do. Whether your state is a state or a metaphor for a state, you have to be an artist – and the more exuberant, the more different, the more iconic, the better. Even for hackneyed superhero sequels. As a king or an auteur, there is no one (besides the Bond Company Stooge) to constrain you – so you can really, completely be yourself. (Arguably, the last English king who could really be himself was Henry VIII.)

Even the most hackneyed superhero sequel has a director – just as even the cheapest taquería has a chef

Sometimes the artist and the autocrat mix in weird 20th-century ways. While Saddam Hussein, very much the artist in command of the state, is best known for his romantic novels, he also hired a legitimate Hollywood director, Terence Young, to direct (or at least edit) a biopic, The Long Days, of his own early life – which was certainly dramatic enough. Saddam lived his own movie. Even in his own sentencing and execution scenes, he is completely in command of the frame. I would like to think Donald Trump would do as well.

I have not seen The Long Days. I am sure it is not good. In the department of actually good films – that is, 1970s films – the great Italian directors Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi, inventors of the mondo genre with Mondo Cane, and fresh off the insane cancellation frenzy of their masterpiece Africa Addio, a colonialist documentary about decolonialization (one of the few great films to have been condemned on the floor of the General Assembly of the United Nations – by no less a figure than Arthur Goldberg, who actually resigned from the Supreme Court to be our UN ambassador, a move that seems completely insane in 2025 but actually felt like a promotion in 1965) decided to atone for their sins by making an educational film about American slavery. Well – a mockumentary about American slavery, 1971’s Goodbye Uncle Tom.

The conceit was that an Italian film crew lands, in a helicopter, on an 1850s Southern plantation, and films itself as it films the actual operations of the plantation, including a dinner conversation whose text is taken entirely from period sources. Perhaps a little disrespectful – but why not learn about the past, eh? Even better: it was filmed in 1970, in François Duvalier’s Haiti, with extras who were poor rural peasants – and had also never seen a helicopter.

Also, because, in Duvalier’s Haiti, there were no rules, at least if you had crisp Italian lire – you could do whatever you wanted with extras. You could starve them for three days, then feed them slop out of a trough, shooting this with handheld sports close-ups as if it were the Foreman-Ali fight, then use jarring intercuts to create a “mealtime on the plantation” montage that sets this dark animalistic scene against, cold, posed shots of Southern and Northern gentlemen debating political ethics over dinner. When normal Hollywood makes a movie about slavery, say Steven Spielberg’s Amistad, it makes you empathize with the slaves. (Excuse me, “enslaved persons.” Get your revenge on the language longhouse, even just internally to yourself, by pronouncing “enslaved,” “unhoused,” etc., the Elizabethan way – with three syllables.) When Italian aristocrats make a movie about slavery… Roger Ebert called Goodbye Uncle Tom “the most disgusting, contemptuous insult to decency ever to masquerade as a documentary.”

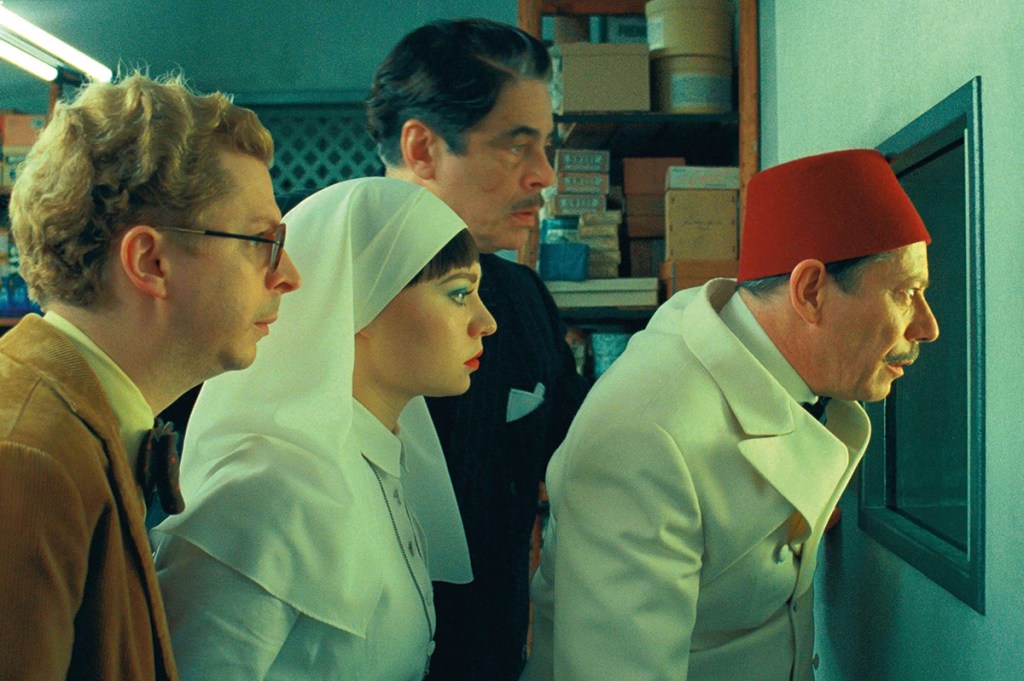

Everything is a dolly shot of dolled-up people in a doll’s house. All of the characters have main-character energy

The Addio Zio Tom story would amuse the antihero of The Phoenician Scheme, an aging Benicio del Toro who is increasingly coming to resemble one of Saddam’s younger doubles. As Anatole “Zsa-zsa” Korda, capitalist mastermind of ruthless international development, he turns a century of Marxist villain archetypes into a lovable rogue. Asked how he will build his megaprojects in the fictional Phoenicia, he replies: “slave labor.” “We’ll pay them a small stipend,” he explains, grandly, while engineering a politically convenient famine.

In 2025, this is the hero we need. Isn’t Phoenicia just Dubai? While Dubai is not governed by lovable rogues, it was invented by lovable rogues – who today has heard of the Trucial States? And it has the world’s tallest building, for roughly the same reason. Also, it’s a monarchy. Doesn’t it feel more like the future there than here? So does China. Which is also a monarchy. Strange coincidence, obviously.

It is unclear why Zsa-zsa Korda has a woman’s nickname. Lots of things are unclear. It’s a Wes Anderson film. It’s OK. It’s beautiful. It pans. Everything is a dolly shot of dolled-up people in a doll’s house. All of the characters have main-character energy: 200 percent main-character energy. Greek ideas are reused – a sort of heavenly chorus, involving Willem Dafoe as some sort of Hebraic angel, and Bill Murray as a very beardy God. It’s not new. It’s fine. The lead actress, Korda’s daughter (and, of course, foil – a novice nun, in fact), is not attractive. My wife had an issue with this. I thought it was fine. Not only should nuns not be attractive – but it brings out the personality. Also, she is playing opposite Michael Cera. (There’s an internet rumor that Cera has an 11-inch member, but it is almost certainly wrong.)

Is Wes Anderson phoning it in? To me this is the important question. The Phoenician world-building seems thin. While the fonts remain as impeccable as the sets (is there a Wes Anderson font library?), at the story level, something of the old obsessiveness is missing. I feel the old Wes Anderson would have gone far more deeply into the magnificent engineering works of Phoenicia. Or something. This carries over to the story arc: do we really care whether Zsa- zsa defeats his half-brother Nubar, Benedict Cumberbatch doing a terrifying splice of Alan Turing and Rasputin? Do we care whether Zsa-zsa’s daughter becomes a nun? We care about Royal Tenenbaum. We care about Steve Zissou.

The very slight soullessness of The Phoenician Scheme, in comparison to “golden age” Wes Anderson, makes the secret ingredient in Anderson’s secret sauce all too clear. It’s not bad. It’s actually very good. But once you know why it’s so tasty, you can’t forget it: Wes Anderson is a Nietzschean. (Researching this hypothesis – at least googling “Wes Anderson Nietzsche” – indeed turns up an undergraduate connection.)

The Nietzschean hero is defined by his main-character energy. Every major Anderson film, from Rushmore to Life Aquatic, has the same fundamental theme: the struggle of superman against man, the Nietzschean hero who makes his own rules and defines his own being, against the bugman longhouse Puritan-Unitarian normie world. Who is Max Fischer but the teenage larval superman, on the verge of discovering his powers? And where Max Fischer is Hamlet, Royal Tenenbaum is Lear. The same person. The hero with a thousand credits.

The old Wes Anderson would have gone more deeply into the magnificent engineering works of Phoenicia

What renders Anderson’s works charming rather than unendurable is that his side characters are Nietzschean, too. Even his women are heroes. Korda’s icy, Biblical, all-knowing daughter Liesl is a young Eleanor Zissou. Liesl is a young prude and Eleanor is an aging femme fatale. They are the same person – equally unique. This is the nature of an aristocracy, the closest thing our gifted-child theater-kid oligarchy has to any actual nobility.

In Wes Anderson’s world, even the cameos are iconic. Even the extras are striking. Anderson clearly loves his whole world and everyone in it. There is always an ugly edge when a director or a novelist hates his own inventions. We feel that he must, in some way, hate himself. Should such a man have power? Over others? Over a film, even?

This is why Wes Anderson was my late wife’s favorite director and why I will always be down to watch his latest film. Perhaps he is phoning it in a bit. World-building is hard. My humble suggestion: switch to docudramas. Watch Paolo Sorrentino’s magnificent and too little known Loro and Il Divo (about Silvio Berlusconi and Giulio Andreotti) – then, it’s obvious. Benicio del Toro as Saddam Hussein…

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 15, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply