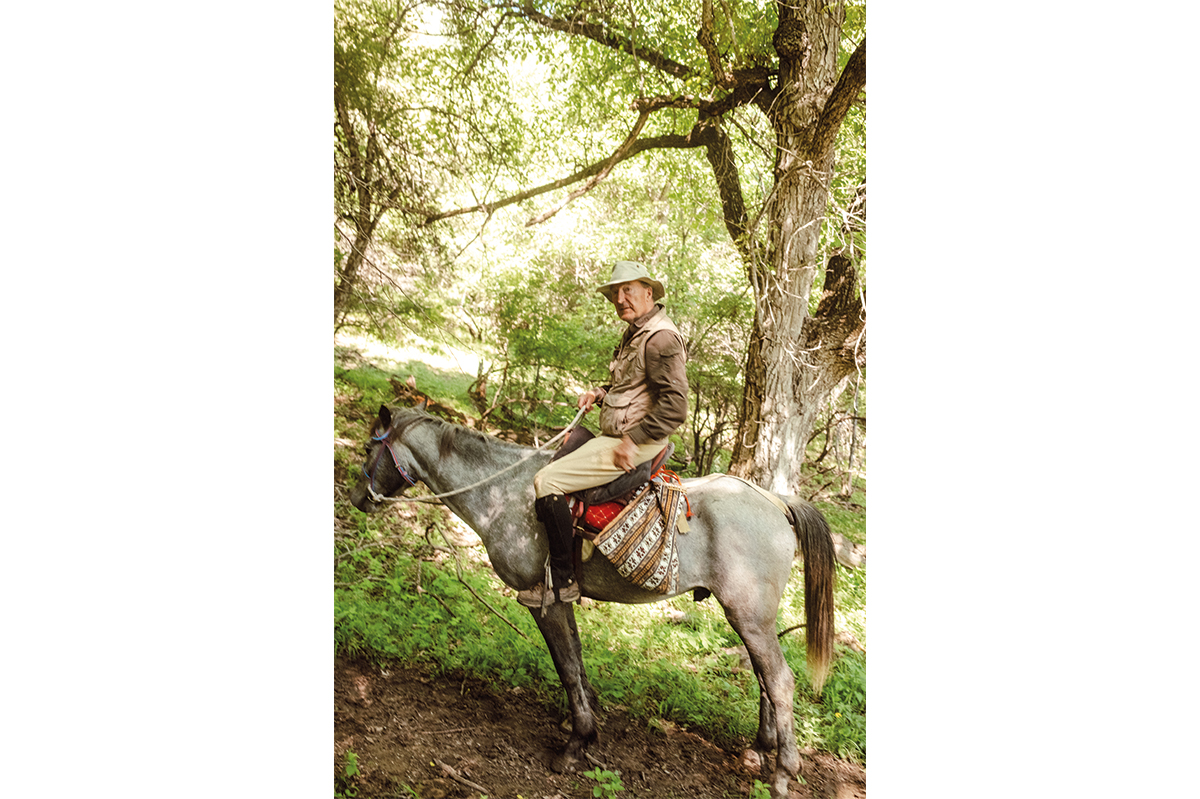

Southwest Virginia, October. Gravel groaned under my creek-numbed feet. I looked up at a mountain laid out like a fist and I climbed toward the most violent knuckle. But before I got there, the world turned on its side. I don’t know for sure why I collapsed. Maybe it was food poisoning, maybe a heart attack. I felt my face resting on cold stone and gripped the dark walnut of my rifle stock as I passed out.

Eleven hours later, a new day started. A distant pickup truck with glass-pack mufflers fired up, then idled in a deep rumble. I stood – before the sun came up – and did squats for warmth, surprised I felt as good as I did, but I had a decision to make: walk off the mountain or hunt my way out. May as well hunt.

I did not grow up hunting bears, and bear hunting is as different from deer hunting as cage fighting is from arm wrestling. More effort, yes, but even more than that, because in bears we see ourselves. Because we’ve castrated him, turned him from wild animal to plush toy. Because we’ve forgotten our tangled past. But I was here to understand it. And to get meat for my family and fat for my friend in Choctaw, Mississippi.

Songbirds chattered and a dead fog masked the valley. My head throbbed and I shivered as I sipped a cold batch of rehydration salts. And the mountain top teased me, lying just a hundred feet upslope. Distant dogs yapped, searching. In time, the sounds came more quickly. Their individual voices, distinct as yours or mine, blended and rose, choir-like. Then all hell broke loose.

I’d never killed a bear before. I’d hunted other animals: deer, rabbits, doves, ducks, turkeys and so on

The dogs’ gleeful barks told me they had driven a bear up into a tree, and I imagined them circling and trying to channel their inner cat and climb.

Feeling stronger than I should have, I started uphill toward them. The most natural thing would have been for a bear or a dinosaur to step out of the thick primeval woods. Neither did, but indentations through the leaf litter told a story I trusted so I followed the trail down the knife ridge toward the road that lay a couple miles away.

My plan was this: sneak along as slowly as I could manage, like eight hours for one mile slow. If I took a bear, I’d dress it, load my pack, hang the rest and walk out. The mountain was a refrigerator, so no meat would be lost waiting for my return.

When the wind blew, I moved. I scratched the leaves to emulate a turkey. Then I’d stand stock-still, listening for any footfall and watching for movement in the vertical world of trees. I’d squat. Study the signs and listen. And so it went, until the sun lay low across the mountain. Bears were omnipresent ghosts.

Something shifted – on the mountain and within me. Everything fell in new rhythms. The limbs of two oaks nearly intertwined as they dropped elongated acorns, pat-pat, pat-pat. A thick-chested hickory dropped large round nuts in rarer thuds. And beechnuts landed like bugs’ feet on the dry leaves.

The leaves were turned up where bears had been eating and there were signs of fresh scat. It wouldn’t get any better than that. So I sat and waited. The animals, I reckoned, would come from the thicker slope. So just over the crest I tucked into the base of a broad oak. Now and again I tossed stones to imitate falling acorns and rubbed them together to imitate squirrels’ teeth grinding on hickory nuts. In time, related or not, squirrels came in. Then turkeys. Then deer. And I willed bears.

When the sun dropped over the ridge, strands of spider silk glowed like blown glass. The temperature dropped. Bear dogs sounded, back in their kennels, resting for tomorrow. In the dying light, thermal currents snatched my scent safely away.

I felt it was about to happen. I stood, leaned into the oak and mouthed what I could recall of that old bear hunters’ incantation, “Now surely we and the good black things, the best of all, shall see each other.”

Then there it was. “Nita,” as my friends in Choctaw, Mississippi know it. I raised my rifle. An American black bear, weighing about 100 pounds or so, stopped and rooted. And I watched him. He had not a clue I was there. There was an intimacy to watching it all unfold so close to me that I could hear the acorns and the hickory nuts popping and grinding in his jaws.

I’d never killed a bear before. I’d hunted other animals: deer, rabbits, squirrels, doves, ducks, turkeys and so on, since I was five or so. But I’d never killed a bear. We didn’t have them to hunt. They’d been nearly extirpated in Mississippi, where I grew up.

My finger considered the trigger. I settled the crosshairs. And when he turned, I lowered my gun and backed away. It wasn’t that I couldn’t pull the trigger, rather that I didn’t feel impelled to do so. It just wasn’t necessary. The adventure was complete. Being so near a wild bear unmolested was the perfect punctuation. That was the climax. There’s just no explaining some things. This was one. I walked off the mountain.

But soon I was back in the mountains with my bow. And that time I walked away with a bear. But that’s a different story.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 15, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply