The sirens began at about 5 a.m. A Houthi ballistic missile was on its way, over Jerusalem, in the direction of the coastal plain. After half a minute or so, I began to hear the familiar sound of doors scraping and muffled voices, as people made their way to the shelter.

It has become a regular occurrence. No one makes much of a fuss anymore. For most Israelis, most of the last 70 years, Yemen was a remote country on the other edge of the Middle East, the part facing the Indian Ocean, rather than the Mediterranean. What was known about it consisted of a few items of food and folklore that the country’s Jewish community had brought with it to Israel when it fled there en masse in the late 1940s. Now, it has become a strange, uninvited nocturnal visitor, periodically launching deadly ordnance at population centers.

Outside Syria, the Iranian losses are decidedly less terminal

The missile, like the great majority of its predecessors, was quickly intercepted and downed. The Ansar Allah government in Sana’a can’t match the Jewish state in either attack or defense. Still, on the rare occasions when the Houthis have broken through, the results are not to be dismissed. They succeeded in closing Ben Gurion airport for a few days back in May, when one of their missiles landed near the main terminal. And in July, a civilian in Tel Aviv was killed when a Houthi drone penetrated the skies over the city and detonated in a crowded street.

Israel’s response to the Houthis’ aggression has been swift and consequential. Extensive damage has been inflicted on the Hodaida and Salif ports, the airport at Sana’a, the oil terminal at Ras Issa and other infrastructural targets. Speaking to me in his offices in the port city of Aden a few weeks ago, Yemeni defense minister Mohsen al-Daeri noted the “huge impact” of the Israeli counterstrikes, describing the airport, Salif and Hodeidah as the “lungs” through which the Houthis breathe.

But with due acknowledgement to Israel’s response, it should be noted that while the Houthis’ lungs may be damaged, they are clearly still breathing. Their continued ability to lob occasional missiles at Israel goes together with their ongoing and far more consequential terrorizing of shipping seeking to pass through the Gulf of Aden-Red Sea route. In the last two months, they have sunk two Liberian-flagged, Greek-owned ships. Traffic through the area remains down by 85 percent compared to the pre-October 2023 period.

In June, I visited the frontlines in Yemen’s Dhaleh province, where the Houthis face off against UAE supported fighters from the Southern Transitional Council. The discrepancy in capacities between the sides was immediately apparent. The STC fighters are well organised, highly motivated and able to hold the line. But in weaponry and in particular in the crucial field of drones, the Iran-supplied Houthi fighters have the clear advantage.

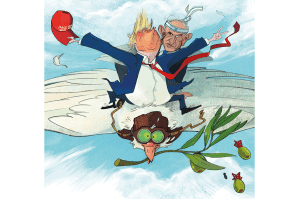

The evident durability of Iran’s Yemeni allies raises a larger question. In Israel (and in the West, in so far as the west pays attention to such things), a trope has taken hold according to which the successful campaign fought by Israel and the US against Iran in June, along with Jerusalem’s mauling of Hezbollah in 2024 have effectively put paid to Tehran’s regional ambitions and broken the Iran-led regional alliance. The very coining of the term “Twelve-Day War” to describe the June fighting is clearly intended to recall Israel’s triumphant Six-Day War in 1967, in which the Jewish state vanquished the armies of Egypt, Syria and Jordan. The 1967 victory broke the forward march of Arab nationalism. The 2025 war against Iran, implicitly, is deemed to have achieved something similar with regard to Tehran’s Islamist regional bloc.

The achievements of the US and Israel against Iran and its proxies in Lebanon, Yemen and elsewhere were without doubt impressive and demonstrated a vast conventional superiority. There are reasons, however, to temper the euphoria and take a close look at the current direction of events. This is important not only or mainly because modesty is a becoming virtue. It matters because failure to note how Iran and its proxies are organizing in the post-June 2025 period runs the risk of allowing them to regroup, rebuild and return.

Of the defeats and setbacks suffered by Iran in the course of 2024 and 2025, only one element is almost certainly irreversible. This is the fall of the Assad regime in Syria. Assad’s toppling has removed Syria from the Iranian axis and turned it into an arena of competition between Israel, Turkey and the Gulf countries.

Elsewhere, however, the Iranian losses are decidedly less terminal. In Yemen, as we’ve seen, Tehran’s Houthi clients have yet to suffer a decisive blow. They have managed effectively to close a vital maritime trade route to all but those they choose to allow to pass. The West and the Gulf are not currently engaged in equipping their own clients to give them an offensive capacity against the Houthis. Unless and until that happens, Iran’s investment in Yemen is set to continue to deliver dividends.

In Iraq, largely ignored by western media, the Iran-supported Shia militias remain the dominant political and military force in the country, commanding 238,000 fighters. They prudently, and apparently on Iranian advice, chose to largely sit out the war of the last two years. But the current ruling coalition of Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani rests on the support of the militias, in their political iteration as the “Coordination Framework.”

The ruling coalition is in the process of advancing legislation that will make permanent the militias’ status as an independent, parallel military structure. In Baghdad in 2015, a pro-Iran militia commander told me that the intention was to establish the militias as an Iraqi version of the Revolutionary Guards in Iran. The current legislation would go far toward achieving this aim.

In Lebanon, too, despite its severe weakening at the hands of Israel, the Hezbollah organization is flatly rejecting demands that it disarm. The government of Prime Minister Nawaf Salam has made clear that it has no intention of seeking to use force to induce the movement to do so. Given Hezbollah’s infiltration of state institutions, including the Lebanese armed forces, it is not clear that the government would be able to employ coercive measures even if it wished to. The continued Lebanese dread of civil war also plays a role here. Only Israel’s ongoing campaign to prevent Hezbollah’s rebuilding of its forces is likely to be effective.

So taken together, what this picture amounts to is that Iran has suffered severe setbacks on a number of important fronts over the last 18 months. But in none of them, with the possible exception of Syria, is it out of the game. The sirens in the Jerusalem night sky are a fair indicator. Complacency would be a grave error. Reports of Iran’s demise have been much exaggerated.