By complete fluke, my delayed shuttle bus rose through the Coast Mountains at dusk. I pressed against the window, outing myself as a tourist amid seasonaires snoozing through another spectacular sunset. Hot pinks and deep purples streaked between towering pines, transforming the outline of snow-capped peaks. I’d crash with local friends for a month, with support from Vail Resorts to explore stories beyond the slopes. Tales of Whistler Kids ski school were already family lore – I’d once visited as a 10-year-old, buzzing to see snow.

Stuck at Vancouver International, I’d pulled up a chair at Salmon n’ Bannock on the Fly – Canada’s only Indigenous restaurant in an airport. As travelers, how often do we pause to ask whose land we’re actually on? I wasn’t thinking about that in 2000, and neither were my parents as we geared up for our first big ski trip. Flatbreads, wild fish and game dishes made clear I was on unceded First Nations territory.

The mountains I’d flown to ski are sacred. They belong to the Squamish and Lil’wat Nations, whose knowledge and care shape these lands. Building luxury tourism here is complicated, no doubt. But done thoughtfully, tourism can support cultural preservation, benefitting Indigenous communities directly.

Jet lag had me blinking snowflakes from my eyelashes, beholden to The Bunker café’s 7.30 a.m. opening every day for a week. I acclimated among a revolving cast of resilient mountain-town types, fueling up for another perfect ski day (or a 15-hour bar shift). Baristas balked at $2,500 room rental listings as I shared a maple bacon croissant with Marina, fresh from a three-week Chilean trek (her dry food arrived by horse – Canadians are tough, I was discovering).

“You see brown bears on your walk home from the bar in summer,” she said. “I just keep walking, fast. Too cold to see ’em now. Too cold to ski! I’m not going up there.”

Bunking in with friends gave me a rare chance to get to know the Whistler Blackcomb behind the brochures. During a long, cold snap (at -15°C/ 5°F, the term hardly seemed adequate), I skipped the mountain to explore the Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Center, one of Vail Resort’s partners. A museum-gallery-café hybrid, it’s filled with carvings and canoes, offering Indigenous-led forest walks, workshops and storytelling. The Audain Art Museum is home to massive Northwest Coast cedar masks, alongside a collection of moody Emily Carr landscapes. I was reminded to swerve any gift shop replicas.

The resort highlights its roots, offering quiet invitations to reflect – like the Peak 2 Peak gondola, its cabins wrapped in Indigenous art. Dotted between Whistler Village Stroll’s thumping bars and clubs are public installations, towering carved Welcome Figures and First Nation statues depicting nature, strength and legend. More snow-covered carvings peek mythically from the slopes. “The Squamish and Lil’wat Nations have agreements with the resort,” my museum guide said. “There are programs now for revenue sharing, employment and training.”

With a new appreciation for the land’s history, I wanted to explore. A trip highlight: Phoebe from Black Tie Ski Rentals pulling up at my friends’ place with three pairs of boots and skis. What luxury, to skip the usual queue in a stuffy rental shop. Owner Todd’s team had dubbed me “aggressive” based on my emailed stats, sparing me the embarrassing shop weigh-in. Village-level exchanges with free swaps make them worth every Canadian dollar, especially in unpredictable conditions.

Something I’d been wary of: TikTok-famous lift queues snaking through town on peak days. On weekdays in February, I found almost none. On weekends, beating the lines just meant getting out early. Pro tip: avoid “the maze” – the Whistler Gondola entrance – and head straight to the Fitz, Garb or Emerald chair route. While tourists wait, you’ll already be carving first tracks down Raven. That, plus a breakfast roll from Splitz Grill, became my daily ritual (after a quick check of Whistlerpeak.com’s webcams). I skied – and ate – like a local: $12 chicken udon at Samurai Bowl and late-night Fuji Market dashes for half-price sushi.

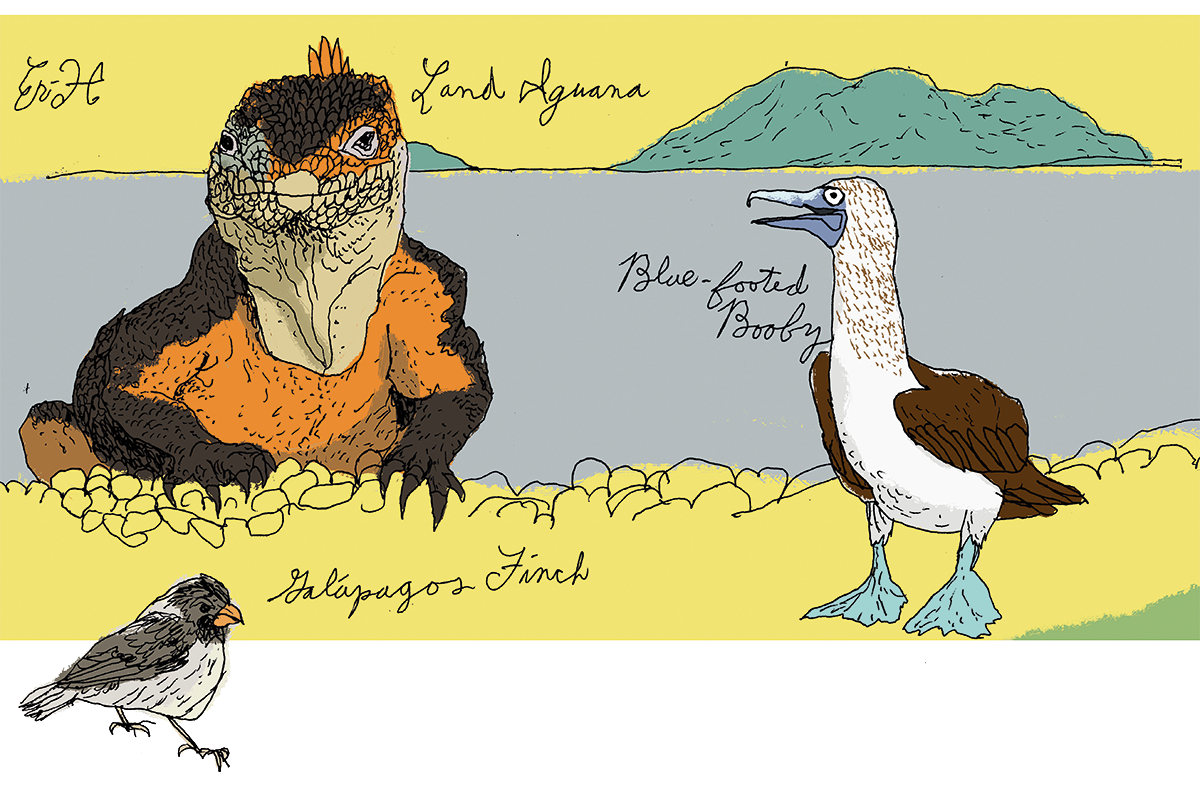

The biggest resort in North America, Whistler Blackcomb’s stats justify the hype. More than 200 runs, 8,050 acres of skiable terrain, 16 bowls and three glaciers for me to throw myself down. I found powder-filled chutes and bowls, tree runs spaced just right and wide-open groomers, plus terrain parks to please the pickiest of park rats.

Embracing my “aggressive” label, I took the Glacier Express to boot-hike Spanky’s Ladder, and drop into Garnet, Diamond, Ruby and Sapphire Bowls. Some of the most thrilling – and humbling – skiing I’ve done, helped by a hip flask of Baileys. A shift from three weeks of drought and sun to 20+ cm of fresh came fast, conditions swinging from wind-packed and crusty in exposed areas to buttery soft in sheltered bowls.

At 7:15 a.m. on a freezing Tuesday, I understood why the die-hards keep coming back (and why lock-ins at Irish bars aren’t advised on ski trips in your 30s). Two espressos down, I joined Dawn Patrol – Whistler Heli-Skiing’s grounded-flight backup. That kicked off several packed days organized by Vail, showing me lines I’d never have found solo. There’s quiet magic in slipping away before the village stirs, carving through untouched powder in total silence. My guide pointed out off-the-map runs only locals know, and by 9 a.m., I was buzzing on adrenaline and sugar. Chic Pea’s oven-fresh cinnamon buns were a fine reward for the brutally early start.

Lunch arrived at Christine’s on Blackcomb, where well-heeled skiers gather for panoramic views, charcuterie boards and rich massaman curry. A local friend jealous of my rather posh itinerary had shared a review: “Order a Bloody Caesar (vodka, clamato juice, Tabasco and celery salt). They used to make you apologize to a turtle if you asked for a plastic straw.” Now, local produce is hauled up the mountain by gondola – a logistical challenge that speaks to their commitment to high-quality sourcing.

Another elevated experience came via a six-course Winemaker Lunch at Steeps Grill & Wine Bar: beautiful regional bottles, delicate plates and 1,850 vertical meters between punters and a red wine nap (the lift’s there if you lack hubris). Also delicious: Spirit Bear coffees and Ravens Brewing beers on the sunny patio at Raven’s / Sḵewḵ’ / Yecwlào7 – the first Indigenous-inspired restaurant at the Creekside Gondola summit.

The Fairmont delivers peak mountain lodge luxury – cozy fireplaces and big panoramic windows. Ski-in/ski-out access sees guests swap skis for hot chocolates by an on-slope fire. The Mallard Lounge has the buzz everyone’s looking for after a day on the hill. Vida Spa’s heated pools, jacuzzis and private barrel saunas are undeniably luxe (I kept it real with a Meadow Park membership). The Gold floor offers a hotel-within-a-hotel setup, with a private concierge and lounge designed for eating cheese in fluffy robes. Fog rolls over the pines as Blackcomb Gin is poured out, infused with cedar tips and Pemberton hops.

At the base of Blackcomb, staying here drops you into the center of nightlife that stretches far beyond boot-stomping and Burt Reynolds shots (those rum-and-butterscotch shooters show up everywhere). Evenings aren’t about the usual ski “scene” so much as subcultures – part fur-trim and velvet ropes, part champagne super-soakers, part open-mic night chaos. Vallea Lumina is a sort-of multimedia night walk through an old-growth forest, gently sharing ancestral stories. Fire & Ice features St’át’imc Nation hoop dancers telling the story of Spo7ez, an ancestral village buried by a massive rockslide – said to be triggered by the mythical Thunderbird to restore peace. It’s a powerful reminder of Indigenous values of coexistence.

Helicopter tours with Blackcomb Helicopters offer the perspective needed to grasp Whistler’s scale. Every hour in the air is offset by forest preservation on Quadra Island, once earmarked for development. Banking over Whistler Peak, I watched glacier walls glow electric blue. Below, skiers traced threads across vast mountainsides, heading for hidden bowls of powder caches. Our pilot pointed out the Cheakamus Community Forest, co-managed by the Lil’wat and Squamish Nations with the resort. Indigenous knowledge shapes modern conservation, ensuring the land is treated with respect.

Whistler Blackcomb delivers on every skier’s dream – but its heart lies in the land’s history and the people working hard to honor it.

Amy’s trip was supported by Vail Resorts.

Rates at the Fairmont Chateau Whistler start from $600 per night (7-night minimum) in winter, and $407 per night (2-night minimum) in summer.

Now is also the best time to lock in the Epic Pass at its lowest price of the year, with expanded access to Verbier and the 4 Vallées, plus the new Epic Friend Tickets for 2025/26 season giving friends of Epic Pass holders major discounts.

More at: www.epicpass.com | www.fairmont.com/whistler

Leave a Reply