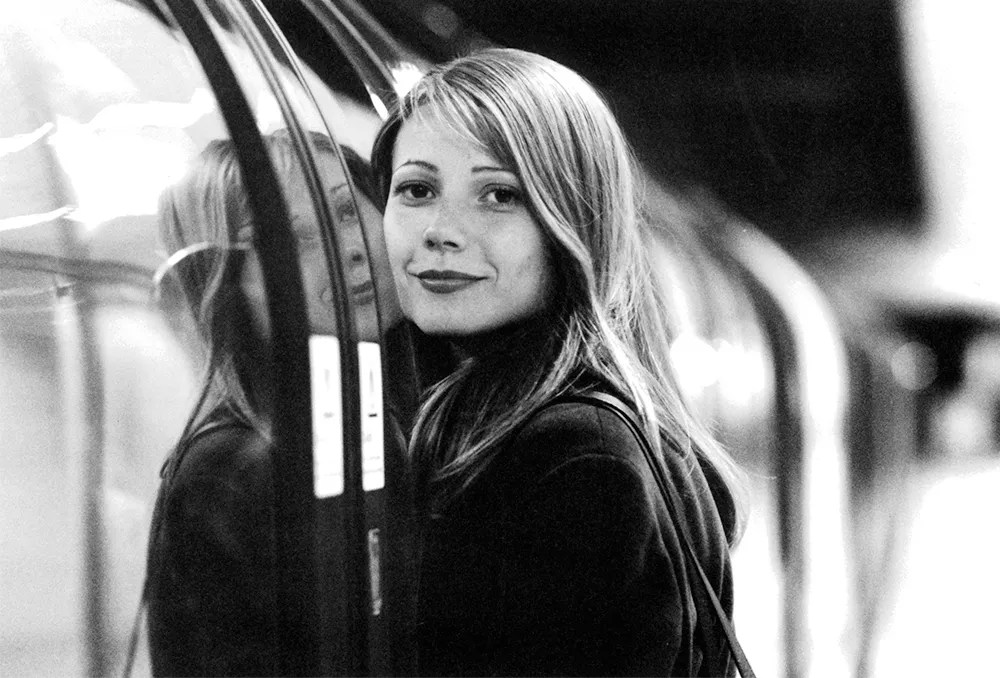

There is nobody who finds Gwyneth Paltrow, 52, more interesting than the woman who was a teenager in the 1990s. This was the last era of the true pin-up, the heart-throb, the movie star as icon, rather than the whiffy melange of brand-pusher, pound-shop activist and reality star that constitutes celebrity today. I was as Nineties as the next girl living in provincial Massachusetts and when I first saw Shakespeare in Love in 1998, Paltrow’s first and only Oscar-winning role as the late-16th-century actress-in-male-garb Viola de Lesseps, I’d never enjoyed anything as much in my life.

And in 2025, Paltrow’s career’s Take Two fascinates the early middle-aged woman who finally gives in to the barrage of wellness marketing sent her way on Instagram. She now finds herself ordering “adaptogens” (plants that are meant to help the body adapt to stress) such as reishi mushroom powder “for immunity” and bovine collagen powder “for hormone balance and joints.”

Naturally, Paltrow’s much-ridiculed lifestyle brand and newsletter Goop, which she founded in 2008 when good acting parts began to dry up, sells its own adaptogens: Paltrow was an early adopter and evangelist of almost every current wellness trend. As we learn here, she is extremely shrewd and, when it serves her, thick-skinned – a curious combination of entrepreneurial survivor and woo-woo artiste.

Altogether, Paltrow’s ability to fascinate and allure has served her very well, as this detailed, gossipy and slightly catty biography by the fashion journalist Amy Odell makes clear. There was something predestined about Paltrow’s success, for “as her parents and their world always taught her, she was just that special.” She was also just that talented, with her ear for languages. She learned fluent Spanish on a school exchange in just a few months and, despite being a New Yorker, managed different English accents for Sliding Doors (1998), Emma (1996) and Shakespeare in Love.

Gwyneth is not just of interest to long-term viewers or followers of Paltrow, but to all students of celebrity, culture, media and the complex interactions between nepotism, talent and sex appeal. What makes it more than a repetitious biography of a movie icon is the subject’s obvious complexities, beginning with her background.

Her parents, Blythe Danner, a stage actress of birdlike frame, was famous, and Bruce Paltrow, a producer, was rich. They were an unusual couple. Danner was anxious, reflective, introverted and always more interested in the art of theatre – stage – than celebrity and success. She was posh and Episcopalian, whereas Bruce was “brash” and Jewish, with a father called Buster. But they loved each other and stayed together – until Bruce, the “love of [Gwyneth’s] life,” died, aged 58, in 2002 from throat cancer. The parents had tried to give their daughter and her younger brother Jake a “normal” upbringing. Bruce cut Paltrow off financially when she dropped out of the University of Santa Barbara to pursue acting, and she waited tables out of necessity.

The family was decidedly cultured, and when Gwyneth was a child went every year to the elite Williamstown theater festival in the Berkshires, where Blythe joined huge names on stage. Theater buffs will relish this roll call of late 1970s and 1980s acting aristocracy. Gwyneth the precocious child was popped into a range of parts, including one in a Chekhov play. Later, when a movie star, she returned in a highly acclaimed turn as Rosalind in As You Like It.

She was born the definition of white privilege and has always been hated – and envied – for it. She got screen roles easily through connections, and with her love of partying, willowy frame and ethereal beauty soon became an haute couture clothes horse and It Girl. Much is made of the importance of being Brad Pitt’s girlfriend in the mid-1990s when he was the world’s biggest heart-throb, but it made her increasingly miserable because, in part, he just wasn’t good enough. He was from ultra-conservative Christians in Missouri and couldn’t understand her Upper East Side sophistication.

There were bad parts and failed movies (Hush, Great Expectations, View From the Top), but her work with Harvey Weinstein at Miramax – she was the studio’s “muse” for a decade – clinched her reputation as a quality superstar. Somehow she survived Weinstein’s rapacity and manipulativeness, but her account of his predatory behavior when filming Emma, when she was 24 and he was 43, provided key early testimony for the first major #MeToo story, broken by Jodi Kantor in the New York Times in 2018.

We see how Paltrow aggressively covets the fine things in life – demanding private jets and suites at the Ritz as a breakthrough star, and she can clearly be a cold, bitchy diva. This is a feature Odell returns to repeatedly, interviewing people who knew her at school, who worked with her on set at different times, and who went from being useful to not useful or, like erstwhile friends Madonna and Winona Ryder, somehow annoyed her.

But for all the garbage, there is also an impressive resilience. Most people who endure half as much loathing and ridicule as Paltrow would be having public mental health struggles. She famously doesn’t care what most people think, and seems to concentrate mainly on her children and her next winning hand.

There is a shrewd simplicity and perceptiveness to some of her pronouncements. Of the idea to start Goop, she says:

I was privy to such good information, and I thought, “Well, if my girlfriends want to know this information, surely other girls and guys may want to know too. So, if they do, I’ll do it, I’ll just put out a newsletter.“

This is perfectly sensible. “I would rather die than give my child a Cup-O-Soup,” she said in 2005, making everyone hate her, again. But her point, brand and personality was at least succinctly presented.

And she can be wise. At one point when her star crested in the late 1990s, her father sat her down for a talk with his bratty daughter: “You know, you’re getting a little weird… you’re kind of an asshole.” Instead of blocking him, as her contemporary equivalent might have done, Paltrow felt “devastated” and thought: “Oh my God, I’m on the wrong track.” This led to an important reflection. By the age of 26, she didn’t:

“…have to wait in line at a restaurant, and if a car doesn’t show up, someone else gives you theirs. There is nothing worse for the growth of a human being than not having obstacles and disappointments.”

Her life in the 21st century as a businesswoman is less interesting than her late-20th-century one because it is a far more commonplace story. But her antennae for the next big thing are nonetheless remarkable. Long before MAHA czar Robert Kennedy Jr. was saying the sun “is good for you” – cancer be damned – Paltrow was saying the same. But few in the MAHA movement ever won an Oscar.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 15, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply