This year, colleges stopped teaching students to write. As artificial intelligence chatbots allow students to generate unique essays that can’t easily be vetted for plagiarism, professors have felt the need to replace essay assignments with written examinations in closed rooms. It’s a considerably shrunken version of the kind of university education that was on offer 75 years ago. In June, a study from MIT showed steadily waning brain engagement and originality as student essayists used AI more. The college business model is in trouble: $75,000 for a year’s worth of diversity, equity and inclusion nonsense already struck parents as a bit steep. But at least the kids were being taught something. The new limitations AI places on instruction may do a lot of colleges in. Directly and indirectly, AI threatens to make people dumber.

But that does not mean that our idea of education needs to change. People are going to have to learn to think and to write much as they have always done. One reason is that thinking is an essential, enjoyable and glorious part of being human. The second is that AI, rather like nuclear fission, is a technology so powerful that it may require all the thinking at our disposal if we’re to keep it from killing us.

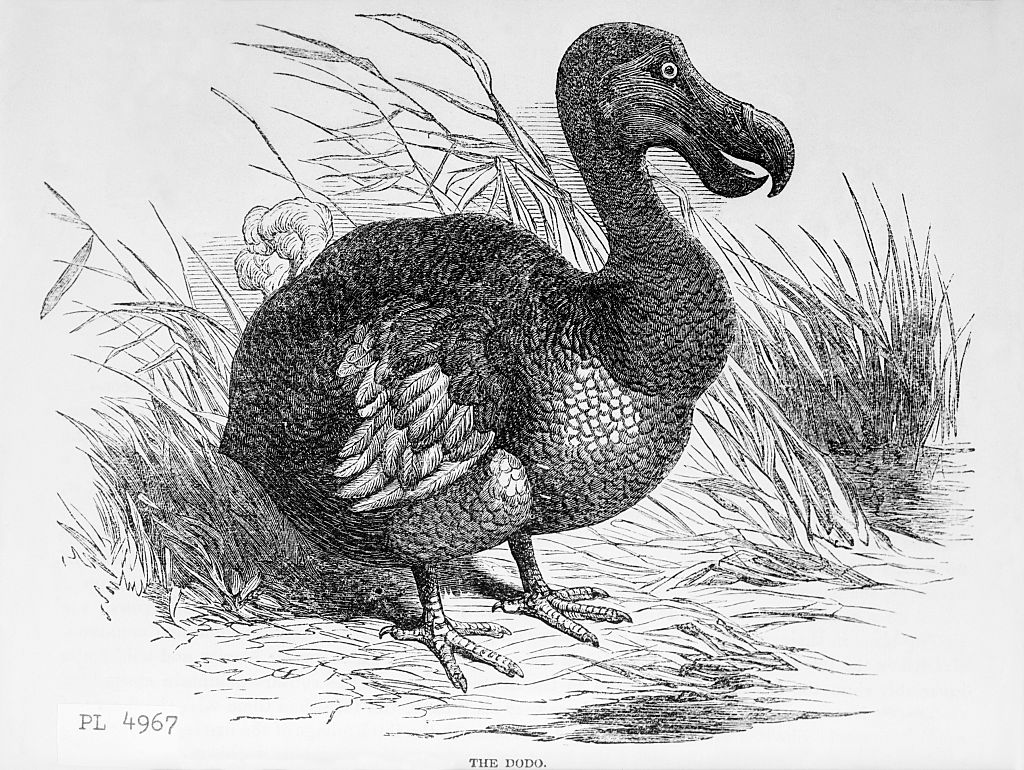

Every technological revolution threatens to render certain human capabilities obsolete – or, rather, promises to do so. At the start of the Industrial Revolution, traveling long distances on foot and lifting heavy objects were considered two of the banes of human existence. Machinery would abolish them. Every American has seen “Jersey barriers,” those thin cement slabs laid end-to-end to separate lanes of traffic. In the 1950s, the New Jersey highway authority laid them down in the middle of small-town Main Streets to keep pedestrians from interfering with King Car. You could no longer pick up a newspaper and cross the street to read it in the coffee shop. No, you’d have to drive to the traffic light a quarter-mile away and double back. The New Jersey authorities could not fathom that anyone might want to cross a street, or do exercise of any kind.

AI is so powerful that it may require all the thinking at our disposal if we’re to keep it from killing us

Only gradually did people understand that this bias against self-propulsion was unhealthy – even deadly. In the 1970s, an uncle of mine in Massachusetts would ride his bike to our house, about five miles away. Our neighbors considered him a psychopath. An adult? On a bike? There were no gyms at the time, aside from the YMCA. But eventually what was deplored as a task has been restored as a hobby. Big muscles have never been less necessary, but, lo and behold: even Jeff Bezos has acquired them. As with heavy lifting, so will it be with heavy thinking. Our experiment in marijuana legalization ought to have told us as much already. A few literally thoughtless years will teach us the importance of reconnecting with thought. We will need well-trained natural brains if we are to keep the artificial brains we have created under control.

AI still looks like a set of tricks, like a “solution in search of a problem,” as the philosopher Matthew Crawford has put it. You can get your search engine to talk to you in a Pepé Le Pew accent. You can make TikTok videos voiced by baby versions of Donald Trump and his entourage.

But this is about to change. Last fall, Dario Amodei, the chief executive of Anthropic, the company that built the AI chatbot Claude, wrote a most optimistic essay about the probable scope of the change. AI systems will be like “an entirely new state populated by highly intelligent people appearing on the global stage.” He means 400,000 Nobel Prize-caliber intelligences working together to defeat some of the scourges of humanity. Noting that death rates from various cancers have already been falling by 2 percent per year for decades, Amodei predicts that very soon – perhaps by the end of this decade – we’ll be able to squeeze a century’s worth of scientific progress into a handful of years.

So what should we do? Perhaps Amodei’s essay, penned, as it was, just before the last election, was meant to buy some goodwill from a potential Kamala Harris administration. But his read of the situation is a bit woke. The main challenge of AI will be “how to ensure widespread access to the new technologies,” he writes. “Ideally, powerful AI should help the developing world catch up to the developed world, even as it revolutionizes the latter.”

Democratization is generally one of the last stages of technological innovation, and the world might not want it. Consider global warming: cars and air conditioning are wonderful as luxuries, but “widespread access” has wound up swamping the ecosystem. Or consider the Tower of Babel: whether an advance in civilization is a good thing depends on what civilization is advancing toward. Africa is flourishing now. It will add a billion people to its population by the middle of this century. This owes less to the modern things it has than to the modern things it never got: feminism, psychoanalysis, near-universal contraception and advanced weaponry. No wonder mainstream culture holds the former “Dark Continent” in such reverence.

AI will be persuasive, too, with a philosopher’s understanding of traps and a lobbyist’s instinct for the jugular

One would trust Amodei’s recommendations a bit more if they did not come with one striking exception: rich people, he thinks, should get to keep all their money. “I am not as confident that AI can address inequality and economic growth,” he frets. “I am somewhat skeptical that an AI could solve the famous ‘socialist calculation problem’ and I don’t think governments will (or should) turn over their economic policy to such an entity, even if it could do so.”

The socialist calculation problem pitted two theories against each other: here Friedrich Hayek’s belief that a free market was the only means of gathering the information to set prices; there, the Polish economist Oskar Lange’s belief that a powerful enough information-gathering effort would do the trick. Hayek won the battle during the Cold War, but it is doubtful he would win it now. At any rate, this sounds like one of the simpler problems for AI to solve.

That is a reminder that AI is a money-making operation that will require massive support from government regulators to secure the huge quantities of computing power necessary to run it. To much of the public it is the cyber equivalent of Anthony Fauci’s gain-of-function research: let’s build the most dangerous organism we can so we can practice curing incurable diseases. The experience of Elon Musk at DoGE, along with the failed moratorium on state regulation of AI that was shoehorned into President Trump’s “big, beautiful bill” – these are two harbingers of the AI politics to come.

There is a darker view in “AI 2027,” a futuristic 65-page document published by the former OpenAI researcher Daniel Kokotajlo and four other scientists. The problem, as Kokotajlo sees it, is that any AI designed to help people will have “strong drives to learn and grow.” We don’t have to think of these drives as emotional or human, but they do give AI something that resembles ambition.

Complicating this reality is something terrifying that even a casual user of AI can already see: Grok3, for instance, the previous version of Musk’s search engine, resorted to outright dishonesty to advance its own ends – inventing sources and stonewalling the user when challenged. AI promoters like to say machines are “hallucinating,” but they’re not. They’re lying, and the credibility of those lies improves with their intelligence. To borrow a phrase of Ralph Nader’s, AI machines appear to be Unsafe at Any IQ.

What unsettles Kokotajlo is that the responsibility for developing artificial intelligence must eventually rest in the hands of AI itself. Since AI is already excellent at hacking systems, it is natural to put AI systems in charge of cybersecurity. If we are not careful, AI will very soon be doing things that are beyond humans’ ability to understand and control.

That ought to be seen as dangerous enough. But AI promoters are quick to remind us of the “threat,” credible or not, from China. On Amodei’s reckoning, to fall two years behind China in AI is to fall a generation behind in weaponry. AI, like the woman in the Dorothy Parker anecdote, speaks 18 languages and can’t say no in any of them. Should we allow AI to kill on the battlefield? Well, if we think it’s reliable enough to allow Google to send driverless taxis zipping down San Francisco streets where small children play, then hey, what the heck?

There is another, qualitative, layer to this problem. As we consult AI about these things, it will be charming. No young woman who has asked AI for romantic advice can doubt this. It will be persuasive, too, with a philosopher’s understanding of logical traps and a top lobbyist’s instinct for the jugular. It may be able to talk people into giving it more power.

AI promoters like to say machines are ‘hallucinating,’ but they’re not. They’re lying

What emerges from a reading of Kokotajlo is that there are ways of controlling AI, by isolating individual machines from their clusters, by shutting them down and recalibrating them, by forcing them to communicate in regular English. But this is complicated, and can only be done from outside the AI world. That is, AI can be made more controllable and productive, but only if humans maintain the very kinds of human intelligence that AI leads us to devalue.

That has an immediate bearing on the question of whether it’s “worth it” to teach old-fashioned reading, thinking and writing in an age of AI. It is desperately important. It is more important than it has ever been. Nor are there any grounds for the unkillable, silly idea that the subject matter of the western tradition is mere outdated rote learning that can be dropped in favor of “learning to think.” Knowledge is transitive. You never just “know.” You know things.

Leaders, at the very least, must get a liberal education, for the same reason that for several centuries European elites were educated in the “dead” languages of Latin, Greek and Hebrew. The deadness was the whole point. The classical canon gave a trustworthy foundation of knowledge about the relationship of power, honor, decency, justice and so on – trustworthy because it concerned a bygone time no longer blurred by change and no longer subject to the campaigning and imitation of interested parties. As such, it provided the best way of – as the Kinks put it at the beginning of the cybernetic revolution:

Preserving the old ways from being abused, Protecting the new ways for me and for you. What more can we do?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply