Peter Thiel is one of the world’s most powerful men. He was an early investor in companies such as Facebook, SpaceX, Airbnb and an early backer of Donald Trump, as a leading donor to his 2016 campaign. He is a friend and mentor to the man who would be president in 2028: J.D. Vance.

Thiel, a multi-billionaire, is also one of the few individuals who clearly have a hand in shaping the future of humanity, so it was disturbing to learn recently that he’s unsure whether humans are worth preserving at all.

In conversation with the journalist Ross Douthat, Thiel was asked whether he wanted the human race to endure. He seemed unsure. “I don’t know,” he said, after a long pause. “I would, I would… there’s so many questions implicit in this.”

We’re primed to think of any existential threat from computers as nothing but fiction

What Thiel is hesitant about articulating is a vision of the future that should concern us all. He and other Silicon Valley investors and entrepreneurs who understand the rate at which the technology is developing have decided that we will soon be inferior to artificial intelligence. They think machines could out-perform and out-think us within a decade – and that they will therefore be both ungovernable and unpredictable.

Thiel and co. have come to think that mankind’s best chance for survival is therefore not to dominate AI but to merge with it – to augment ourselves and become transhuman. They imagine a future in which most humans spend their days living, not in the real world, but in a better, virtual world courtesy of advanced AI.

Marc Andreessen, another billionaire Trump backer, has suggested this may even be the ethical thing to do: “The vast majority of humanity lacks ‘reality privilege,’” he said. “Their online world is, or will be, immeasurably richer and more fulfilling… Reality has had 5,000 years to get good, and is clearly still woefully lacking for most people.”

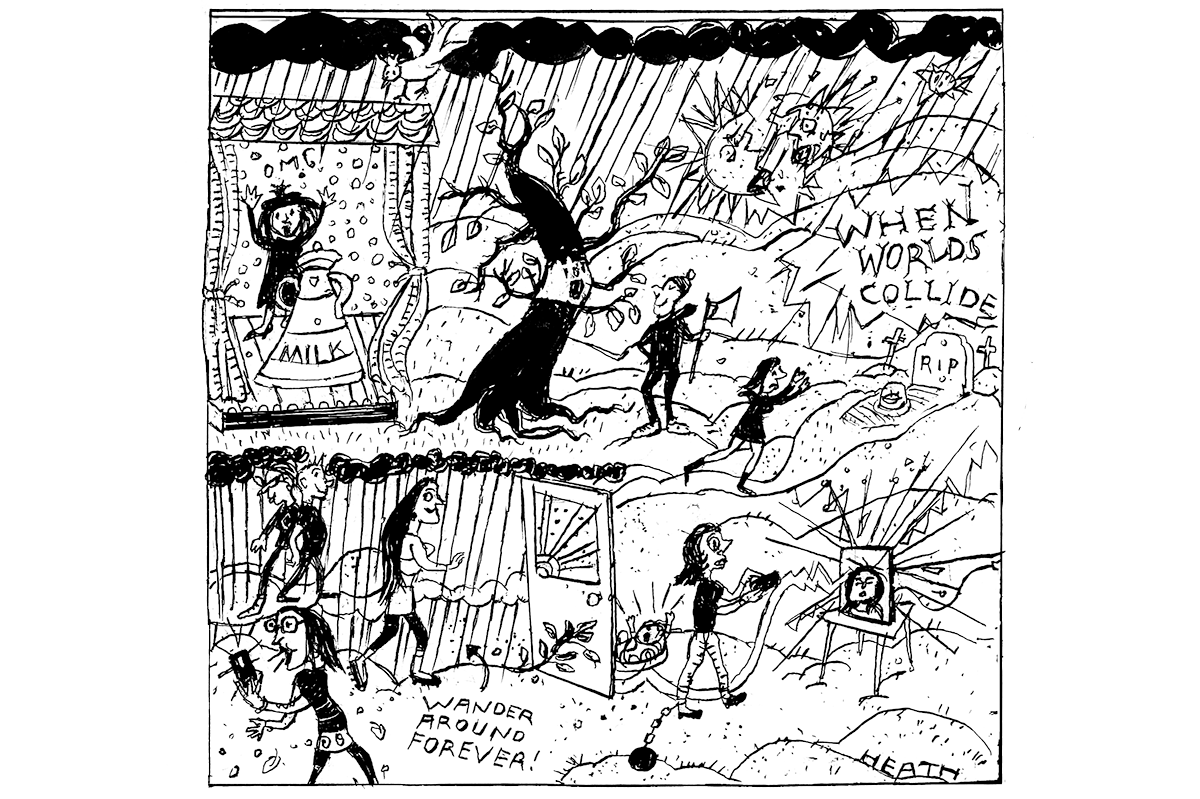

We have put together this special AI edition of The Spectator because we disagree. The value of human life, and of the reality we belong to, does not lie in its lack of suffering. A life of non-stop online entertainment is not a life well lived. We must think about how to coexist with AI now – and how to ensure it genuinely benefits humanity – before it becomes dominant.

As AI expert Marc Warner says in the issue: “We might be charging into the most consequential technological transformation in human history and while that is superficially acknowledged, there is really very little being done about it.”

This is not to say that we should or could seek to stop the development of AI. As Elon Musk and Thiel have both noted, the past few decades have seen a great stagnation. As AI develops in capability it could provide the renewed burst of technological innovation humanity needs. What’s known as “narrow” AI is already making medical breakthroughs and has the potential to eliminate road deaths, transform agriculture, help solve the climate crisis.

J.D. Vance said in February that “the AI future is not going to be won by hand-wringing about safety. It will be won by building.” He’s right. The economist Tyler Cowen is also right to ask “What kind of civilization is it that turns away from the challenge of dealing with more intelligence… dare I wonder if such societies might not perish under their current watch, with or without AI?”

But there is no link between technological and moral progress. Every great human invention brings with it both opportunity and great danger. The same printing press that made the modern world was used to produce The Communist Manifesto. The same railways that sped up journeys facilitated the Holocaust. The same nuclear reaction that Ernest Rutherford discovered would, three decades later, be used to kill up to 225,000 Japanese citizens.

If western politicians are slow to wake up to both the dangers and the opportunities of AI, it could be because the idea of humans fighting robots was such a staple of late 20th-century Hollywood. We’re primed to think of any existential threat from computers as nothing but fiction.

A decade ago, the philosopher Nick Bostrom wrote a now-famous book, Superintelligence, in which he warned us that there’s no reason to think superintelligence will see the value in human life. The robot mind of the future might, without qualm, Bostrom imagined, turn us all into paper-clips if it considered paper-clip production to be its chief objective. Politicians and thinkers across the world read and debated the book, but they failed to take it seriously.

Perhaps we can, though, persuade people of the immediate danger of AI which is that, as it rises, so we humans decline. We suffer a kind of spiritual death as we outsource more and more to the machine. This alone makes the task of navigating AI perhaps the greatest challenge of this century.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply