The masked gunmen of Jaish al-Adl are probably not the kind of people Donald Trump had in mind when he talked about “regime change” in Iran. A terror group in Iran’s southeastern Baluchistan region, they have a bloodthirsty record of shootings and suicide bombings, all part of a jihad for a separate Baluchi homeland. They are, however, excited by Israel and America’s bombing campaign, which they see as a once-in-a-lifetime chance to achieve their goal. As they declared recently: “We extend the hand of brotherhood to all the people of Iran to join the ranks of the Resistance.”

How long that brotherhood would last is another matter. A hardline Sunni jihadist group, the Jaish al-Adl, or Army of Justice, is a world away from the secular, democratic-minded liberals the West hopes might replace the ayatollahs. Few other Iranians share their aspirations for an independent Baluchi homeland, which would tear off about a tenth of the country’s landmass.

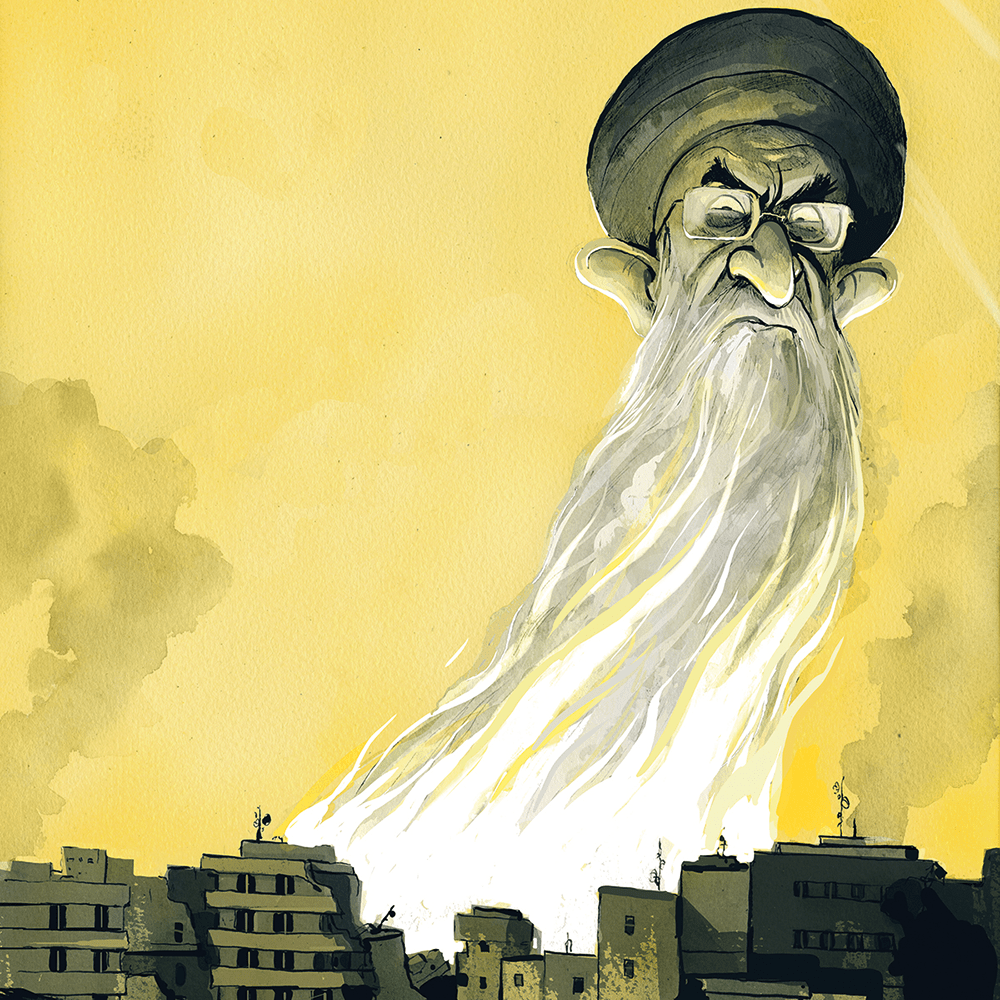

Yet should Iran have another revolution – a successor to the Islamic one that installed the mullahs back in 1979 – and Ayatollah Khamenei fell, groups such as the Jaish al-Adl may feel their moment has come. Just as the mullahs were originally part of an opposition network that included liberals, communists and nationalists, any Iranian Revolution 2.0 could involve a messy uprising of different interest groups, not all with compatible agendas. And as with Tito’s Yugoslavia, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and Gaddafi’s Libya, the mullahs’ fall could see all kinds of long-suppressed grievances aired, with consequences far beyond Iran’s borders.

History has taught Kurdish groups that it is in times of strife that their chances for self-determination come

Take Baluchistan, a swath of desert and mountains that has much in common with the restive tribal areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan, both of which it borders. Most of its people are Sunni Muslims, a minority in Shia-dominated Iran. A decades-long insurgency has claimed the lives of thousands of Iranian security forces, fueled by claims that Baluchis are routinely discriminated against. Baluchis came out in solidarity during 2022’s nationwide Mahsa Amini protests, sparked by the death in custody of a Kurdish student accused of not wearing her hijab properly. In what Baluchis now refer to as “Bloody Friday,” nearly 100 Baluchi demonstrators were killed in a single day – the deadliest of all the government crackdowns during that year’s unrest.

The idea of Iran’s Baluchi separatists seizing their moment has also alarmed neighboring Pakistan, which has a separatist-minded Baluchi minority of its own. Baluchi militants there have carried out attacks on Pakistani security forces and on Chinese workers building a port on Pakistani Baluchistan’s Arabian Sea coast, a big new hub on Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The prospect of Iranian and Pakistani Baluchis seeking an independent “greater Baluchistan” together would imperil the port’s future and, in turn, Pakistan’s. As a Pakistani government spokesman put it recently, the potential fall of Iran’s regime “imperils the entire regional security structures.” There are similar jitters in Iraq, where the Shia government that replaced the Sunni dictator Saddam Hussein has long been sponsored by Iran. The loss of Tehran’s backing could rekindle the Sunni-Shia civil war that tore Iraq apart 20 years ago.

Iran also has Arab separatists in the country’s southwest and Kurdish separatists in the country’s northwest. The Kurdistan Free Life party, allied to Turkey’s PKK militants, has called for a return to the mass street protests of 2022 – although so far they have stopped short of urging an armed uprising. History, however, has taught Kurdish groups that it is in times of strife that their chances for self-determination often come. The thriving Kurdish enclave in northern Iraq started life in the no-fly zone created after the 1991 Gulf War. Its Syrian equivalent, Rojava, a Kurdish enclave, was carved out during the early years of Syria’s meltdown.

The separatists, though, aren’t the only armed groups who might thrive if the regime collapses. Eastern Iran is a key part of the transit route for Europe-bound heroin, smuggled in from the poppy fields of Afghanistan by heavily armed trafficking gangs. Since the early 1980s, nearly 4,000 Iranian police and soldiers have died in the clashes with the traffickers, who sometimes have links to the Baluchi separatists.

Iran has built vast networks of trenches, minefields and forts to thwart them and executes hundreds of convicted traffickers every year. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Iran typically accounts for around two-thirds of global opium seizures and up to a third of global heroin seizures.

There is little sign of Iranians rushing to take up Trump’s suggestion for a Make Iran Great Again movement

The country has a huge addiction problem itself. I saw this for myself in 2008 when visiting former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s hometown of Aradan, where a whiff of opium hung in the air: about half the townsfolk smoked the drug, a local doctor told me. Nationwide, approximately three million of Iran’s 90 million citizens use opium or heroin regularly – one of the highest rates worldwide.

While Tehran’s war on drugs is in part self-interested, it also helps stem the flow of drugs to the West. A regime collapse could repeat one of the unintended consequences of the Shah’s downfall in 1979, when the borders again went temporarily unpoliced. The result was the tidal wave of heroin that flooded into British cities in the early 1980s.

But as of the time of writing, there is little sign of Iranians rushing to take up Trump’s suggestion of replacing the clerics’ regime with a MIGA (“Make Iran Great Again”) movement. So far, the only demonstrations that have taken place in Iran have been pro-regime ones. Anti-regime activists appear to be biding their time, aware that with the clerics already under pressure, the crackdown is likely to be even harsher than in 2022, when around 500 protesters were killed and nearly 20,000 people were arrested.

It’s also the case that as in Saddam’s Iraq and Gaddafi’s Libya, decades of oppression mean there is no unified, well-organized democratic opposition, no Václav Havel waiting in the wings. The National Council of Resistance to Iran – descendants of a Marxist group which helped overthrow the Shah and were then repressed by the clerics – are frequently quoted by British parliamentarians as potential successors. Most ordinary Iranians, though, see them as just another bunch of fanatics, who would replace one cult-like rule with another. Another possibility is the late Shah’s son, Reza Pahlavi Shah, who has a following in so-called “Tehrangeles” – the wealthy Iranian diaspora in Los Angeles. But memories of his father’s brutality run deep, and while some Iranians might accept him as a temporary figurehead, a return to monarchy would be anathema to others. Western-based opposition groups are also wary of repeating the mistakes made in post-Saddam Iraq, where politicians who had spent decades in comfortable exile failed to get traction when they returned home.

Maneli Mirkhan, a French-Iranian activist and campaigner for women’s rights, says there is little appetite for all-out dismantling of the state, as the Americans attempted with de-Ba’athification in Iraq. All that’s required, she says, is to replace the regime figures who occupy the upper half of the pyramid. She also plays down the separatist threat, which she says the clerics exaggerate. “There are small groups who want independent homelands, but the mainstream ethnic political movements, I think, will settle for federalist arrangements.”

Whatever happens, it seems unlikely that any regime change will be peaceful. The regime’s enforcers, the 125,000 strong Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, were set up by Ayatollah Khomeini with the specific intention of protecting the Islamic Revolution from outside challenge. Unlike Saddam’s Republican Guard, it is well-trained, ideologically committed, and unlikely to go down without a fight. Backing the IRGC are also 90,000 Basijis – plain-clothes thugs recruited from working-class neighborhoods, deployed as loose cannons on those brave enough to protest.

I saw them in action while covering Iran’s presidential elections in 2009, when allegations of vote-rigging saw protesters for the first time openly calling for the Supreme Leader’s downfall. Around 70 people were killed and nearly 4,000 arrested during the unrest that followed; the theocracy’s legitimacy has never really recovered.

That it is still intact 16 years later, however, shows that, if nothing else, it is adept at clinging on to power. As Vanda Felbab-Brown, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution puts it, the regime “may now be weak externally, but their internal apparatus is still there.”

The only common ground may be to appeal to Iranians’ long-established sense of nationhood

Indeed, if there is a spark for an uprising, it is more likely to come from inside than out. While Benjamin Netanyahu has tried to stir things up by bombing Tehran’s Evin Prison, where generations of political prisoners have languished, Iranians are unlikely to respond to Israeli prompting. But coming weeks and months could see any number of “Persian Spring” moments, be it food or fuel shortages, spontaneous demos, or some random outrage like that which took Ms Amini’s life in 2022.

At that point, says Mirkhan, “progressive and pragmatic” figures within the regime itself may throw their lot in with the protests, and one or more of them might fit the bill as a transitional leader. None, though, is likely to declare such intentions right now, lest they end up in what remains of Evin Prison.

“It’s possible those people are already having conversations with the opposition overseas, but if their names became public they’d be finished,” says Mirkhan. Even so, it is hard to see a transitional figure who would be universally acceptable in a febrile post-Khamenei Iran. All regime insiders are, by definition, Islamists. But Islam has been institutionalized, debated and abused so much in Iran that it may no longer act as the rallying point that it did in 1979 – if anything, quite the opposite.

As one young Iranian writer once put it, decades of misrule by “perennially self-righteous” clerics is no great advert for organized religion. Instead, the only common ground may be to appeal to Iranians’ long-established sense of nationhood – separatists notwithstanding.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply