The best time to call is the weekend. Or early in the morning. Or late at night. Definitely not when he’s on the golf course. If he’s alone, he’s more inclined to chat. If he’s in a good mood, you might get a few minutes. If he’s in a bad mood he’ll be brief, but you’re still liable to get a usable quote.

That’s how White House reporters describe cold-calling Donald Trump, perhaps the most accessible president in American history. He’s not the first to smuggle a cell phone into the White House: Barack Obama insisted on keeping his BlackBerry throughout his time in office, despite the angst it caused his staff. But you couldn’t just call Obama. You can just call Trump.

“He uses his phone as a weapon of his office,” says Piers Morgan, who has known Trump for decades and speaks with him regularly. “It’s two-pronged: one aim is to gather information and to sound people out and get a feel for what people are thinking, but also, when it suits him, to impart information.” In his second term – having been elected in 2016 as a political neophyte, rejected in 2020 and exiled in disgrace, only to storm back to office last year with a staggering 77 million votes – the President is more confident and brash than ever. Which means he’s more eager to talk to the press on the record and tout his behind-the-scenes mastery of the office.

Trump also has a phone now. In his first term, journalists had to call the White House switchboard and make their way through several layers of vetting to reach the President. Or he had to pick up the phone and call them through that same circuitous process. “The White House would call,” says one veteran cable news host who remains close to Trump. “He wouldn’t dial me directly. You’d get the White House and they’d say, ‘We’ve got the President for you.’”

His advisors ran a tighter ship back then, controlling his methods of communication for all the obvious security reasons. The President of the United States is, after all, the most powerful person in the world. It remains unfathomable to people who have worked in past administrations that hundreds of people have Trump’s private cell phone number. When they cold call him, he tends to answer.

A new trend has emerged in recent weeks as a result: whenever news breaks from the White House, Trump hops on the phone to a slew of reporters and TV news anchors, who proudly take to X or live television to reveal they just spoke to the President and have the latest.

‘He has to be, by a country mile, the most accessible president in the history of the presidency’

When it comes to close allies Trump has known for years, such as Fox News host Sean Hannity, he often phones them first. “The calls go both ways,” a senior source at Fox told me, explaining that the President keeps in regular contact with many at the network, from hosts such as Maria Bartiromo to reporters such as Peter Doocy.

Outside of Fox, journalists have to work a little harder for access. Many try their luck, calling Trump’s personal cell phone directly when news breaks and hoping he picks up. “He doesn’t save people’s numbers,” one White House reporter says, “so he never knows who it is.”

The list of White House cold callers is long and growing. After Trump’s explosive fallout with Elon Musk in June, which peaked with Musk’s suggestion that Trump was covering up the crimes of the late sex criminal Jeffrey Epstein, he had calls with a series of reporters – Dana Bash of CNN, Jonathan Karl of ABC, Robert Costa of CBS and Bret Baier of Fox – to trash the tech billionaire as having “lost his mind.”

The night Israel launched a surprise attack on Iranian military and nuclear facilities, Trump hopped on the phone with Bash and Baier, as well as Fox & Friends co-host Lawrence Jones and Morning Joe co-host Jonathan Lemire. When the United States bombed three of Iran’s nuclear sites, he chatted with Jones, Hannity, Barak Ravid of Axios, Steve Holland of Reuters, Josh Dawsey of the Wall Street Journal, and Yamiche Alcindor of NBC News.

“Journalists, even ones he doesn’t like, can just call him,” says Morgan. “And they’ve got a reasonable chance that he’ll take the call and give them some quotes.”

What’s perhaps most striking about the collection of journalists Trump gossips with is that, with a few exceptions, they are hardly the media boosters one would expect. In recent years, Trump has attacked Bash (“nasty”), Baier (“hostile” and “nasty”), Karl (“third-rate reporter” who will “never make it”), Costa (“lightweight lapdog”) and Alcindor (“racist”). According to Dawsey, his “38-second call with the President” ended with a plea from Trump: “I hope you’re nicer to me than you usually are!”

Trump is sometimes less generous with his time. Cold calling “doesn’t always work,” one White House reporter tells me. Sometimes Trump will end the call when reporters identify themselves, as he did recently when Karl phoned about Iran.

All this conferring with the supposed enemies of the people has raised a question among Trump’s supporters in the media: why is he taking calls from the high priests of the traditional press and not doling out these scoops and quotes to the MAGA voices that got him elected?

“It’s a bit jarring because I just don’t feel like the commander-in-chief should be consulting with anchors or reporters,” says one pro-Trump podcaster who spent decades as a cable news host before going independent.

So why does he do it? Reporters I spoke with offered a simple explanation: Trump, a famed gossip, simply loves taking calls. “It’s not that complicated lol – he likes to answer his cell phone,” one reporter covering the White House texts. “He likes to talk. He just answers. If he’s in a good mood you might get a few minutes. A bad mood, a very quick soundbite.”

Morgan agrees that the success of the cold call is a matter of Trump’s emotional state. “It depends what mood he’s in, or if you get him at the right moment,” Morgan says. “The morning after the election, which he’d won at 2 a.m., I left it until about 9 a.m. and called him thinking, ‘I don’t think he’ll pick it up.’ He did, and we had an amazing chat.” Since the election, Trump has called Morgan “out of the blue” on several occasions – just to talk. “I had a text exchange with him yesterday,” Morgan says. “He has to be, by a country mile, the most accessible president in the history of the presidency.”

The incentives for the journalists who launder Trump’s half-baked thoughts and grand pronouncements are plain. Infusing on-air commentary with the magic words “I just spoke with the President” lends your reporting a flourish of authority, not to mention a punch of immediacy as the rest of the media regurgitates the same piece of breaking news over and over again. The inside track is a buzzy place to be, even if being there reveals nothing more than what we already know.

“The quotes are always terrible,” says one White House reporter who has stopped calling the President because of how little it yields. “But it’s good for the networks to say, ‘We have a reporter who can just call up the President.’”

There are also risks to running with a bit of gab from Trump. “It can be a pitfall,” says another political reporter, who recalls an incident in which NBC News correspondent Garrett Haake reported on a conversation he had with Trump about a bill being put forward by Republicans during Joe Biden’s administration. Trumpworld duly accused Haake of misrepresenting his comments and canceled an upcoming sit-down interview the candidate was supposed to have with NBC. Inside the Trump campaign, the reporter says, there were discussions about giving the interview instead to Sara Murray, then a CNN reporter – and Haake’s ex-wife – in retaliation. Yet the messy dust-up did little to hurt Haake’s access to Trump; they still chat regularly.

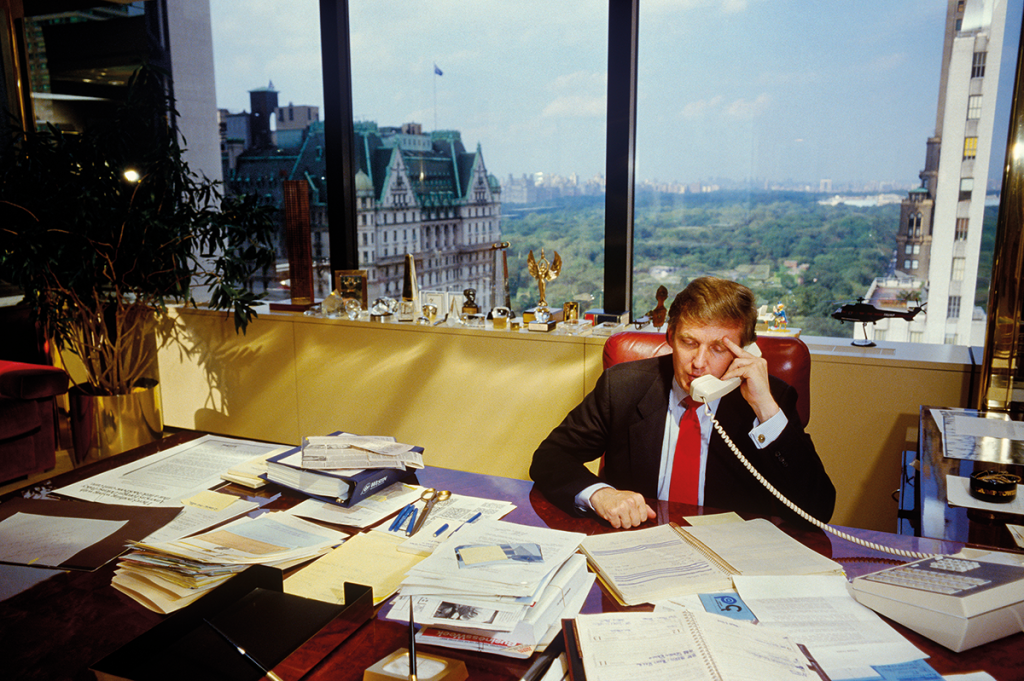

Trump’s love of the phone call is nothing new. His penchant for gossiping with reporters goes back to his days as a young real-estate scion from Queens who barreled his way into tabloid headlines by virtue of his irrepressible urge to talk. If this weren’t such well-trodden ground, I’d rattle off the list of tales from that far more innocent Trump era, during which he’d ring up reporters – sometimes as himself, sometimes as his fictitious PR man John Barron – to dish about the latest building he had erected or, indeed, the last erection he had.

Back then, the ploy was a thinly veiled strategy to manipulate the press. It was almost too easy for Trump, who added a dash of spray-tan spice to the otherwise dull pages of the city’s business papers. Never mind that much of what he said was exaggerated or made up out of whole cloth – he was generating headlines.

As the late New York Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin observed in 1991: “The guy was buying the whole news industry with a return phone call. The news people provided Trump with the currency of his life, publicity, and he believed it was real and the news people believed him right back.” Like those calls, the ones Trump treats reporters to in 2025 are framed always with Trump as the hero and his foes as failures. “I just spoke to the President of the United States,” Hannity said as he kicked off his special coverage of Trump’s strikes on Iran. “Maybe it’s a little early to go there, but this will go down in history as one of the greatest military victories.”

The world changes but Trump stays the same. Decades after the young real estate baron incensed Breslin with his effortless command of New York’s press, his mastery of the return call is as sharp as ever.

There is something refreshing about it. After years of presidential administrations carefully orchestrating their messaging from the Oval Office, Americans are being treated to an unprecedented close-up – thanks not to any feat of hard-hitting journalism but just because the commander-in-chief can’t resist taking yet another call.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply