On the wall of a dive bar in Washington, DC, hung a poster for Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger. The bar had the same name as the film. The movie (more boring to watch than metal melting) follows a disillusioned Anglo-American journalist roaming the African desert, indifferent to the landscape and the war he’s supposed to report on. He trades identities with a dead arms dealer and leaves behind his wife, job and old life, thinking that doing so will fix the emptiness. It doesn’t. He is incapable of caring. He has no convictions, not even when living in danger, not even when he meets someone new.

The Passenger tells the story of Western men who have become indifferent observers with no cause to embrace, men who seek meaning in escape rather than responsibility. It is, in many ways, a perfect reflection of today’s Washington, DC, and America more broadly.

Passenger the bar, however, contained everything the movie’s protagonist couldn’t find. It was simple, raw and real – until June 30, when it closed. It was a gathering place that offered honesty in a city that dresses and talks only to impress, a city that now struggles to find its purpose.

Passenger was a disaster. The floors were sticky. The bathrooms were riskier than unprotected sex. The drinks were bad. The chairs were broken. Sometimes I was the only customer. On live-music nights meant to draw a crowd, bands often sounded so bad that they should have been sent to Guantanamo. Once, five people were shot outside. People kept drinking.

Most of my friends hated the bar. When I shared the news of its closing in our groupchat – named after another bar – the reactions came fast. “RIP to Passenger and its disgusting cocktail menu,” one said. “Best news I’ve heard in a while,” another typed. “Why are they shutting down?” a friend asked. “Rhetorical question?” someone else chimed in. “This is what capitalism does,” one replied, getting a little too serious for a Monday afternoon. “Now, don’t be too Italian,” came a text in response.

Despite the disdain Passenger evoked, people kept showing up. Because Passenger – as much as it sucked – never pretended to be anything other than what it was: a place for honesty in a city built on performance.

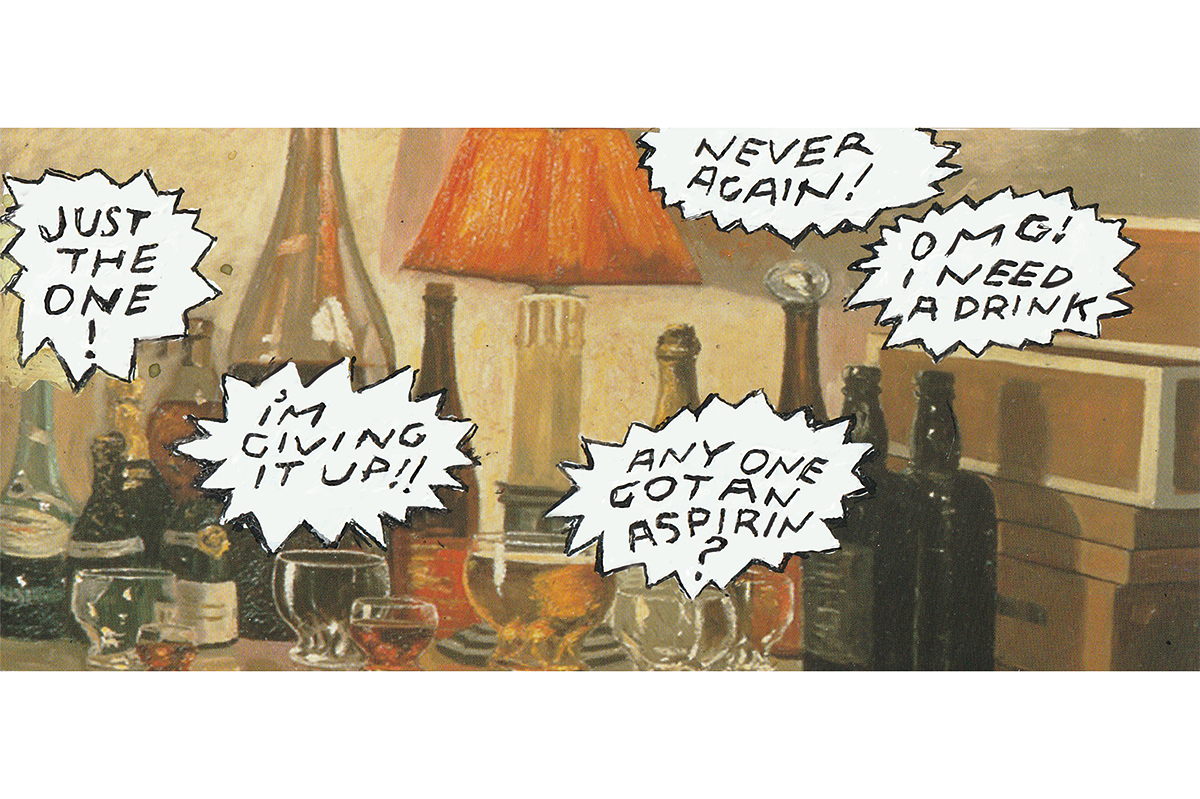

From Rick’s Café in Casablanca to New York’s Stonewall Inn and Prague’s Café Slavia, bars have long served as stages for revolution and change. Every city has one. Paris had Café de Flore. Barcelona had Bar Marsella. Don’t get your hopes up though: Passenger wasn’t so grand. History didn’t happen here. Only hangovers. It was the sort of hangout Ernest Hemingway would have liked, but for losers.

I went there after protests, after Russia invaded Ukraine, after breakups, elections, embassy events and, once, a funeral. For years, I dragged people there: aspiring World Bank economists, someone just flown in from Brussels, Washington Post columnists, CNN commentators, Hill staffers, secretive diplomats, foreign-policy idealists and cynics, journalists kidnapped by pro-Russian separatists, struggling philosophers, Democrats and Republicans.

The world’s successful shared drinks with the world’s failures. Those with tax-exempt status sat next to those who haven’t filed since 2015. Suits and sweatpants bonded over cheap beer and jokes. My mother always said the only things that matter in life are relationships. Nothing mattered more at Passenger.

Tears and laughter and cigarette smoke filled the air. A boy told me there that he had never loved anyone more, then told me he had never loved me. Someone joked that we could be married in Venice, if we didn’t spend so much cash on the bar’s claw machines. Someone else explained to me the military implications of the fall of Bakhmut, Ukraine, on a Tuesday night.

Passenger was the opposite of everything DC pretends to be. Friendships and encounters existed without agenda – the setting was too unglamorous for anyone to pretend to be glamorous. The bartenders didn’t care who you were. They only cared about whether they could bum a cigarette and whether you could avoid puking over the counter. If you couldn’t? Well, nobody’s perfect.

Passenger didn’t die from mismanagement. It was killed by the new religion of glossy, clean, sterile “safe spaces” promising curated reality rather than unfiltered experience. The place wasn’t healthy. It didn’t come with locally sourced oat milk or sugarless tonic water. It didn’t attract people obsessed with looking good rather than being good, or people who want to pay $25 for a spicy mezcal margarita.

Antonioni had it right: finding meaning or purpose might be hard. You may never get there. But along the road, we need a place to stop – a place that offers community. Passenger didn’t offer great cocktails. But it did offer friendship.

Like all humans, Passenger was filled with sadness, laughter, alienation, comfort and the hope that someone else was feeling the same thing. If Paris is worth a mass, Passenger was worth a hangover.

Drinking will continue. (That, too, is the human condition.) But the thought of sipping a Negroni anywhere else terrifies me.

Leave a Reply