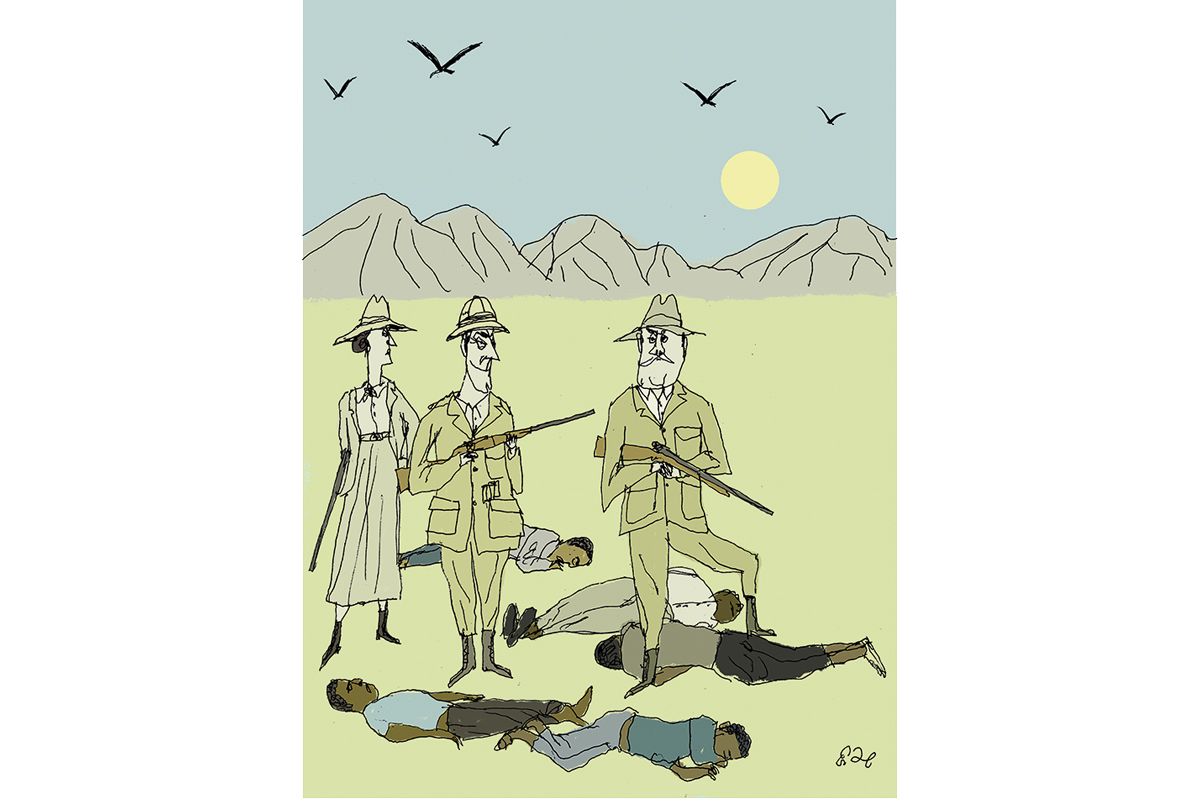

Syria’s Alawite communities are in the grip of a fear that their women and girls could be kidnapped and held as sabaya, or sex slaves. After the Assad dictatorship fell, amid revenge attacks by militias loyal to the country’s new rulers, there were reports of abductions for rape and even of forced marriage. Alawite human rights activists say that some women are still being held prisoner and that kidnappings are still happening. They accuse the Syrian authorities of being unwilling or unable to stop it.

The activists say that between 50 and 60 women and girls have been taken. These numbers are small compared with the 1,600 or more civilians killed in a spasm of sectarian violence in March. Sunni militias rounded up Alawite men and boys to be shot in the streets; some – as I wrote at the time – were made to crawl to their deaths howling like dogs. But the idea that jihadis are trying to revive the practice of taking sabaya holds a special terror for Alawites. There are some credible accounts from families and in a few cases from the victims themselves.

Samira, who is 23, says that she escaped after being abducted, gang-raped and sold into a forced marriage. That isn’t her real name, of course. She’s too scared to allow it to be published. We speak over WhatsApp using a translator. She tells me she was snatched off the street while visiting the city of Homs in February. This is her account of what happened:

A white panel van daubed with mud for camouflage – “a military vehicle” – pulled up and six men wearing balaclavas jumped out. Samira ran but they caught her and threw her into the back. She thrashed around as the van moved off, trying to free herself while hands gripped her arms and legs and punches rained down. Then one of the men raised his boot and stamped on her face. “I didn’t move after that.”

They blindfolded her and the van drove on for about an hour. When it stopped, they removed the blindfold and she saw a half-finished house on a piece of stony ground. She was pushed inside and up the stairs to a room with low sofas. Some of the men kept their balaclavas on; some didn’t. Some wore the jihadis’ short galabeya, which stops above the ankles (as Mohammed wore his). Some had black headbands with the first part of the Shahada in white script: “There is no god but God.”

A woman sat on one of the sofas, another victim, in her fifties perhaps, hair graying at the ears. She didn’t say a word, just stared into space. Samira’s blindfold went back on and her hands were tied. A man took her phone and called her family. She heard him say it would be 500 million Syrian pounds – almost $40,000. “If you don’t pay, we’ll send you her hand.”

As night fell, however, one of the men said he would take her home. Her heart leapt. He led her away, but just to another room that had a mattress on the floor. He tried to take off her clothes. She struggled, so he called in another man. They forced her to undress. One held her down, the other raped her. “I fainted. When I woke up, there were seven people in the room. They took turns.”

The next morning, Samira found herself alone. She opened the door and started down the concrete stairs. Someone hit her on the back on the head with a rifle-butt and she crumpled. She was dragged back to the room with the mattress. This time, four men raped her. They called her “unveiled whore” and “Nusayri pig,” a sectarian insult. Days passed with more rapes. In between, she was left blindfolded, hands tied. She remembers two ropes, one green, one brown. She grew very weak.

They told the woman, ‘No one paid for you’ and shot her in the chest, a single bullet from a Kalashnikov

One day, the men ordered Samira and the older woman to go down the stairs and sit on the bare concrete floor. They told the older woman, “No one paid for you” and shot her in the chest, a single bullet from a Kalashnikov. Somehow, the woman remained sitting upright, her legs slightly splayed, blood gushing from her chest. The men told Samira: “Say your prayers.” She threw herself to the ground, fingertips touching their boots, begging for her life. “I was shaking all over.”

But they didn’t kill her. They told her to lay down and they collected some of the other woman’s blood in a bucket. They poured blood on the ground next to Samira’s head and they took pictures, apparently to fake her death. That evening, she understood why. An older man arrived, in his sixties, and the others called him ‘emir’ or prince. She had to shower and dress and he made her turn around, inspecting her. Then he handed the men a suitcase full of cash. She had been sold.

The emir gave Samira a black niqab to wear and took her to sit in the back of a Range Rover. Pointing to a pistol on his hip, he said: “If you make a move on the road, I’ll shoot you.” She begged him to say what was going to happen to her. “I saved your life,” he replied. “They were going to kill you like that other woman. I paid for you. You belong to me. It will be like I am your husband; you will do everything I say.”

She stayed with him in a house somewhere in the northern province of Idlib. She did not want to speak about that period, just saying: “I wish I had died before I went there.” He seemed to be someone important: officials visited his home; he was never stopped at checkpoints. She managed to convince him that she had accepted her fate and he let her call her family. They had already held a funeral for her after seeing the photos posted on social media.

After that Samira was taken to Lebanon, smuggled across the border. The emir kept her in another house watched over by an older woman and a young man who seemed to be his relatives. He often traveled on business, threatening to behead her whole family in Syria if she tried to escape. Though she was terrified, she eventually screwed up the courage to steal a key and sneak out of the house while he was away. The emir called Samira’s parents to say he would kill them unless she came back to him. She remains in hiding. As she told me, she is “thrilled” with her new freedom but “crippled” with fear.

I was introduced to Samira by an activist named Inana Barakat. She is outside Syria but talking to the families affected, often after seeing anguished appeals for help posted on Facebook or X. She has counted 56 abductions of women and girls. Twenty-five were returned to their families, most after being raped, she says. The rest are still missing. She tells me that ten of the victims are under 18, the youngest 15, the oldest 55. She talks of sabaya, female captives held as sex slaves according to the jihadi interpretation of sharia. Families are keeping their daughters home from school, she tells me. “They are living in a state of fear.”

There are claims of other cases. A 23-year-old woman, travelling with her 11-month-old son, disappeared while waiting on the street for a taxi. Nothing has been heard from her since. A 29-year-old housewife, married with children, disappeared after going to a hospital appointment. Ten days later, her family got an audio message from her. She sounded strange. “I’m out of the country and married. Don’t ask about me and don’t worry about me.”

The historic practice of taking female slaves was reintroduced by ISIS during the brief rule of the “Caliphate” in Syria a decade ago. Thousands of women and girls from the Yazidi minority were held and openly traded in slave markets. I interviewed two sisters in their teens who had been kidnapped by their father’s gardener, who enjoyed their humiliation. A woman in her forties told me she had been bought by a man too poor to own a car and who had wanted a servant. He and his wife turned her out when she got cancer. There were many such stories.

The group that now rules Syria, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS, never took slaves. But there are almost certainly former ISIS loyalists in its ranks. Occasionally a fighter in one of the militias backing the government is spotted still wearing an ISIS patch. It may also be that common criminals are opportunistically taking advantage of chaos in Syria. It was a question during the Syrian uprising – as kidnapping and looting spread – whether criminals joined some of the armed groups, or if some of the armed groups turned to crime. It was probably a bit of both.

Human-rights activists say the police often don’t want to investigate when an Alawite woman or girl disappears, or they try to blame the immediate family. In some cases, girls have posted videos saying they ran away to get married. The authorities point to these videos as evidence that no crime has been committed; the activists say the girls are being coerced. The activists say that all kinds of violence are continuing against the Alawites. One posted a video of a restaurant being attacked by bearded gunmen for selling alcohol. They fear the future in Syria is Islamist and authoritarian.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban Mark 2 returned to power promising a new, more liberal version of rule by sharia. Now they are as hardline as ever. In Syria, the international community is giving President al-Sharaa’s new government the benefit of the doubt for the time being. He was put into power by a wide coalition of armed groups. His government may be too weak to protect the Alawites; some of his men may not want to. Can’t or won’t? For the families whose wives or daughters were taken, it makes little difference which.