Beirut

The customs man wore a white linen suit. He had a large moustache. His ample belly touched the edge of his desk. The scent of cardamom wafted over as a tiny cup of coffee was placed in front of him. I was not offered one. This was Beirut airport in the summer of 2011. We were travelling on to Syria, next door, where a civil war was beginning. The customs man lazily flicked through my passport and took another sip of coffee. ‘Everything will be seized,’ he announced with satisfaction. Television cameras, satellite phones and flak jackets were taken away. ‘They were going to put you in jail, too,’ our fixer said, when he arrived, ‘but luckily for you my father is a judge.’

Weeks later, we got everything back. Of course our paperwork had been in order, our lawyer said: ‘They wanted a bribe.’ The problem for the customs man had been how to broach this delicate matter. As anyone who has done business in the Middle East knows, there is a certain etiquette to the payment of baksheesh. For a foreigner to hold out a pile of notes would be insulting. For the official to demand it openly would involve loss of face. An intermediary — your fixer — is needed to smooth the transaction. The exception is Egypt, where policemen on the street will ask you for a ‘tip’. But for the locals from Cairo to Casablanca, there is always some fat toad behind a desk demanding money.

The Arab Spring uprisings were an eruption of anger at this. People could live with the petty bribes but not with the feeling of being trapped by the stultifying corruption. A young street seller in Tunisia, harassed and extorted every day by the police, reached such a pitch of frustration that it seemed entirely logical to set himself on fire — this was how the whole thing got started. In Syria, I knew a smuggler called Abu Mohammed who paid tens of thousands of dollars to the mukhabarat — the secret police — to carry on his business. He expected this, but he couldn’t bear to think that he and his children would never succeed with an honest business. ‘You have to have wasta,’ he said: regime connections. He was a gangster down to his gold chain and his tracksuit, but he martyred himself in defence of Babr Amr, the first piece of ‘liberated’ territory in ‘Free Syria’.

Babr Amr was retaken by the regime long ago, along with the rest of the surrounding city of Homs; Aleppo and eastern Ghouta have surrendered too. As each opposition-held area fell, fighters and civilians were bussed to the northern province of Idlib, now the last place in rebel hands. As many as three million people are there and the rebels are preparing to make something like a last stand. The regime began its offensive at the weekend. Anyone who has watched Syria for the past seven years will have a deep sense of foreboding about what comes next.

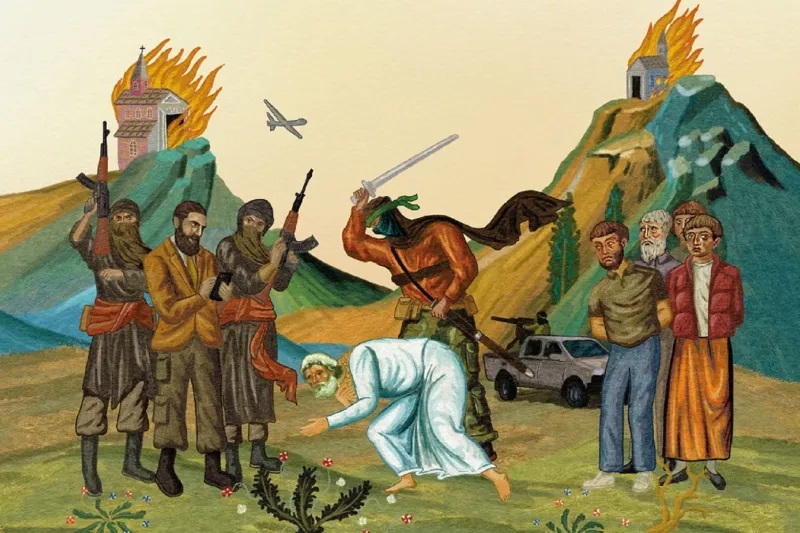

It is true that at the start the street protests were quickly replaced by an armed insurgency. The Syrian government has always characterised the uprising as ‘terrorism’ supported by outside powers such as Saudi Arabia. But at each turning point in the conflict, the regime has seemed ready to escalate first. Chants were met with clubs, stones with bullets, and bullets with artillery and aerial bombing, often indiscriminate, sometimes seemingly deliberately targeted at hospitals or bread queues. Russian planes are bombing now on the southern and western fringes of Idlib, as they have done in other regime offensives. ‘They have already hit the hospitals,’ said Ahmed Mahmoud, an aid worker in Idlib. ‘They always do that first.’ Ten thousand people were on the move, he told me. His charity, Islamic Relief, and other aid agencies estimate that as many as 700,000 could flee towards the Turkish border.

American officials fear that the regime will use chemical weapons ‘again’. Under President Trump, the United States has bombed the Syrian military twice for using nerve agent and chlorine gas. With no independent witnesses in rebel-held territory, there is no absolute proof about chemical weapons — though western governments and UN experts say the evidence points to the government. The regime and Russia have issued a statement accusing the rebels in Idlib of planning a ‘provocation’ to get the US to intervene. The opposition say this statement is a sure sign that the regime is preparing a chemical attack.

Haid Haid, a Syrian analyst at Chatham House, said the cost of this to the regime would be small, another pinprick American missile strike; while the gains might be large — panic among the rebels and a government advance without losses. ‘Idlib will be more difficult for the regime to capture than other areas. A chemical attack would terrorise people and push them to surrender.’ If the opposition and western governments are right, this is a calculation Syria’s dictator, Bashar al-Assad, has made before.

Ahmed Mahmoud, the aid worker in Idlib, said civilians there took the threat of a chemical attack seriously but it was not their main concern. ‘People don’t care which weapon kills them. They say it’s time for the world to witness the suffering from all the other weapons used constantly throughout the last seven years.’ Syrians in the opposition-held areas felt betrayed, he said. The world had watched and let the slaughter continue.

Idlib is different from other places attacked by the regime, though: Turkish troops are there. Russia and Turkey failed to agree a ceasefire but Russian planes will still have to be very careful not to hit Turkish positions when they bomb. And civilians can flee the fighting as far as the border, which has a large presence of Turkish troops. It is unlikely that the Syrian government will capture the whole of Idlib. At the very least, a buffer zone will remain at the border.

Many of the rebels will be able to go to this buffer zone, but not all. Turkey has backed ‘moderates’ against Islamists, including Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which as the Nusra Front was the main al Qaeda group in Syria. The Islamists steadily grew in number as the civil war ground on. Disillusioned fighters swore allegiance to Isis as well as al Qaeda. They were joined by foreign zealots, including Britons, who now find themselves trapped in Idlib. After years of war, parts of the opposition now look like the jihadists the regime always imagined it was fighting.

This will be the last chapter in the Syrian civil war and a coda to the Arab Spring. Assad has assured his personal survival and the survival of the system of wasta, baksheesh and the mukhabarat, though now the spoils go to warlords and war criminals. It will be business as usual, only worse. In Idlib, many thousands will start the winter without shelter, clinging to the hills along the border. In Syria as a whole, the fat officials will still be behind their desks, demanding bribes. The toads have won.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.