The tech sector, we are forever being told, has a gender problem. Recently, for example, Women in Technology International reported that only a quarter of US information technology workers are women – something which it was quick to claim was a result of ‘unconscious bias’. How else, it invited us to ask ourselves, can the proportion of women in technology be so low when women receive 57 percent of college degrees and nearly half of professional degrees in law, medicine, and the physical sciences?

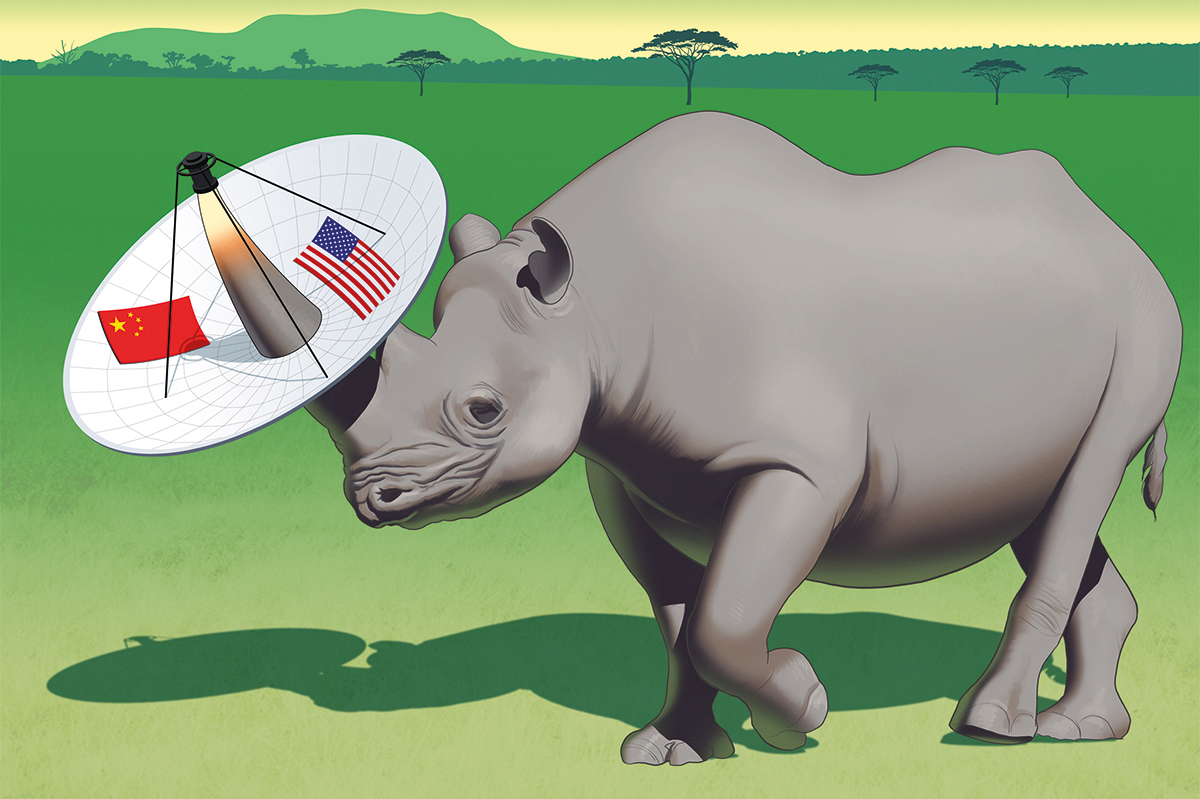

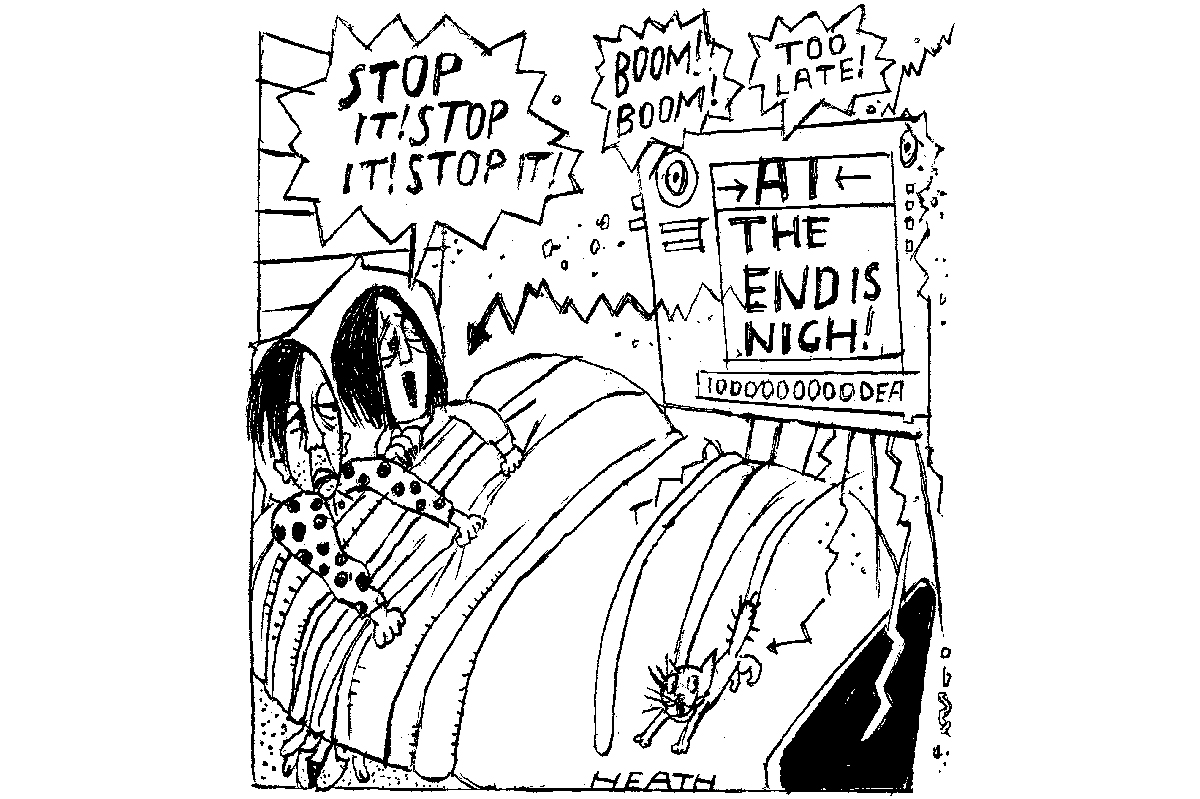

Worse, we are led to think, the bias is inbred in the machines themselves. Last month, Reuters reported how Amazon had built, and subsequently scrapped, an artificial intelligence recruiting tool that inadvertently disadvantaged female applicants – though the tool was never actually used in hiring decisions. It generated an array of tech-bashing columns and think pieces lambasting Amazon – and the tech sector as a whole – for its supposed sexism.

Yet the deeper you look into it, the harder it becomes to sustain the idea that the tech sector is engaged in mass discrimination against women. The Amazon story does not tells us anything about unconscious bias, only about how artificial intelligence (AI) works – and its limitations. There was no bias built into the Amazon algorithm. Rather, the computer models were taught to look for ideal candidates based upon the résumes of successful past candidates over the last 10 years. The simple fact was that the vast majority of those résumes came from men.

Amazon’s algorithm picked up on the different words men and women use on resumes, penalizing resumes that contained the word ‘women’s’ as in ‘women’s book club’ or ‘women’s basketball team,’ and demoting graduates of two unspecified women’s colleges. Those terms were absent from the resumes of former employees, who were overwhelmingly male. The artificial intelligence program also favored resumes that used more ‘masculine’ verbs, like ‘executed’ and ‘captured.’ The exercise may have pointed out the uselessness of delegating your recruitment process to an algorithm, and it was soon dropped by Amazon without ever being used. It may have reminded us of the existing gender imbalance in the tech sector. But that is all.

Still, that won’t be enough for people like Marie Hicks, a professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology, who, in a column at The Guardian, argued that women were forced out of programming jobs at the dawn of the computing age, and that today’s tech companies are ‘building tools that roll back the advances of women in the workforce, as the industry undoes the civil rights protections enacted to ensure that what happened in early computing does not happen again.’

As well as the Amazon story, Hicks referred to an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaint filed against Facebook in September. Three women brought the complaint, claiming that Facebook’s ad filtering prevented them from seeing job opportunities posted on Facebook by independent employers. Job opportunities in construction, trucking, and software were targeted toward male Facebook users.

Yet that is the whole point of Facebook: to target advertising according to demographics and other information gleaned about you from your online habits. If you want to break out of the occupations followed by your own demographic then why rely Facebook to do your job-hunting? Companies target specific demographics with job advertisements all the time, not necessarily to avoid applications from certain candidates, but to devote resources to potential candidates who are more likely to apply.

There are plenty of other industries other than tech which have a statistical gender bias, but without the fuss. Less than 10 percent of construction workers and just over 5 percent of truck drivers, for example, are women. But few complain about this – it is a gender gap accepted as being attributable to women’s choices. Though definitive survey data on what women think about construction or trucking don’t exist, a 2009 peer-reviewed meta-analysis of sex differences in interests confirmed the conventional wisdom: that women prefer to work with people, while men prefer to work with things. A 2005 UK survey, though an imperfect substitute for information about the American labor force, may be indicative of the truth. In the United Kingdom, an Equal Opportunities Commission survey found that only 12 percent of girls would be interested in construction jobs. If so few women are interested, companies may find it more productive to advertise jobs to the group that already makes up a majority of their workforce, rather than branch out.

How can employers in the tech sector be expected to hunt for female recruits when few women have chosen to acquire relevant qualifications? The gender gap in the STEM jobs simply tracks the number of women pursuing STEM educational degrees. To go back to the Women in Technology International report, it may be true that women hold 57 percent of college degrees, but crucially they only obtain 18 percent undergraduate computer and information sciences degrees. If anything, women are overrepresented in the computer science field, given that they hold a quarter of all technology jobs.

We have had no shortage of explanation as to why women make up such a small share of Silicon Valley employees, from James Damore’s now-infamous defense of the biological explanation to the feminists’ sexual harassment explanation. But the answer is likely much more simple than we’re desperate to make it – that women may simply prefer other lines of work.

Sexual harassment and discrimination certainly does occur in the tech sector, but there’s no evidence to suggest that it is more prevalent than in other white-collar industries. Women have overcome bias in other male-dominated fields by working hard and standing up for themselves. The tech industry does not present a unique challenge to women’s equality. In fact, panicking over gender discrimination could actually harm women in the long run. Not only does that signal to women that they are victims, it creates the illusion that women want an unfair advantage or a handout. Women are rational beings, capable of making their own choices and charting their own courses. Promoting the notion that women are victims of an unfair system does not empower women, it undermines their progress and perceived worth.

Amelia Irvine is a Young Voices contributor whose commentary on gender and politics has appeared in USA Today and National Review.