“C’est ma faute,” I called up to the local old boys as they strolled past my potager, chuckling among themselves. I tried to match their levity, but it was obviously affected; they could sense my panic. It was late-April and my garden resembled an eccentrically out-of-season Halloween scene, with tomato plants standing eerily motionless like infant ghosts, wrapped from head to toe in protective fleece.

Everyone knows that 41°F is too cold for tomatoes, but spring had been deceptively warm, and I couldn’t help myself. AccuWeather had issued a grim prediction for the night’s minimum temperature. Only a few days previously, I had been openly proud that my plants had been in the ground for two weeks. I felt foolish and impetuous.

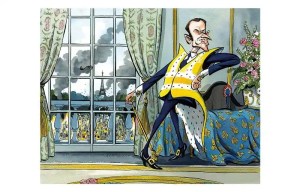

It’s only a matter of time before some local wag tries to diminish my dominance, citing climate change

You see, I had flouted a cardinal French gardening rule. It was still more than two weeks until the Saints de Glace, the three mid-May feast days that cultivators of warm-season crops have watched for centuries. Only after “Saint Servais has sung” (May 13) should any sane gardener even think about planting out tender crops such as tomatoes, eggplants and zucchinis, lest they perish under a late frost. My neighbors, I suspected, had been quietly waiting – perhaps even willing – for me to fail.

I wouldn’t have described the British as an optimistic bunch before moving to the south of France. But it’s only when you live somewhere with more than 300 sunny days a year that you retrospectively appreciate the mental fortitude Britain’s climate demands.

Growing up in middle England, I had come to associate sunshine with happiness, leading me to naively assume that the southern French must enjoy a naturally upbeat disposition. Wrong. In fact, my tendency to look on the bright side often renders my fellow villagers suspicious and uncomfortable.

Even non-gardeners felt compelled to remind me about the Saints de Glace, taking it upon themselves to issue dire warnings. Most of these je-sais-touts have never sprouted a broccoli seed and wouldn’t recognize an organic soil amendment if it were liberally smeared across their faces, yet they don’t miss a beat in dishing out horticultural advice. Over the years, I’ve learned to just smile and nod. On verra. There’s no point arguing. What’s more, my French isn’t up to it. I must let my plants do the talking.

And so, a little after midnight, armed with two five-gallon cans of scalding hot water, I wheeled them down through the gloom. My squeaking wheelbarrow did its best to betray my stealth and the steep inclines threatened to tip me over, but I eventually made it to my patch. I had calculated that ten gallons of 185°F water would emit around 12,000 BTUs of much-needed heat over five or six hours. Enough, with luck, to create a small protective microclimate around my tomato ghosts, bolstered by their fleeces, until the sun rose the next day. These are the lengths to which I go to be the glitch in the French matrix. I can’t let the naysayers win.

By morning, I was back at the garden, casually moving my hot water bottles out of view before anyone noticed. The plants looked absolutely fine. My Bluetooth thermometer – tucked discreetly in a nearby tree – reported that it only gone down to 47°F. The old boys shuffled past again, their faces unreadable. One grunted a greeting at me. I muttered a casual “jour,” leaving the bon unsaid, like a man too busy succeeding to bother with formalities.

I finished unwrapping my spectral tomato plants, feeling slightly foolish for having lost my horticultural cool. Damn you, AccuWeather. Perhaps, I mused, the Saints de Glace are not really about frost at all. Maybe they are a kind of cultural insurance against rashness – an institutionalized warning not to get ideas above one’s station, horticulturally or otherwise. Naturally, I disregarded such a warning completely.

Still, as I secured an apical growth tip and marveled at the almost indecently vigorous leaves on my cerise noires, I allowed myself a small, private gloat. My plants were weeks ahead, and though Saint Mamert, Saint Pancrace and Saint Servais had yet to clear their throats to sing, my tomatoes were already humming. AccuWeather, if it can still be trusted, says I’m in the clear.

That said, it’s only a matter of time before some local wag tries to diminish my dominance – citing climate change, or chalking it up to English eccentricity. I shall, as ever, feign a look of mild surprise and murmur something vague about favorable microclimates. It seems to work. After all, in a land ruled by saints and skeptics, a little heresy goes a long way.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply