In 2014, in the course of his inquiry into shamanism, the anthropologist Manvir Singh spent time with the Mentawai people on the Indonesian island of Siberut. He estimated that among the 265 residents he managed to interview, 24 were male shamans, or sikerei. These “specialists,” as he puts it, were uniquely empowered to commune with spirits and provide a range of services which included healing, divination and raining down afflictions on enemies. Over the course of two extended visits, living on a diet of fried grubs, boiled pangolin and pigs’ testicles, Singh witnessed ceremonies characterized by “turmeric coated sikerei decked out in leaves and beads… the dissonant clanging of bells and the hellish squeals of sacrificed pigs.”

One such ceremony was to heal a young boy who had become dangerously ill because, it was believed, someone in the clan had not shared meat. Angered by such stinginess, the crocodile spirit Sikameinan had sneaked into the clan’s longhouse and radiated a sickness, sapping the boy of strength. A group of sikerei sang songs, inviting Sikameinan into a bowl of water which they carefully carried to the river and emptied. When the sikerei returned, they recited a Christian prayer and ate a celebratory meal, leaving with the best pieces of meat.

Singh writes that when he tells people he studies shamanism he usually gets two conflicting views of it. The first, that it is “primeval wisdom,” a remnant of our once true spirituality and connection to nature. With our shift to industrialized cities, we have abandoned this wisdom, “subjecting [ourselves] to depression and meaninglessness.” The second is that it is “superstitious savagery,” a relic of a bygone era produced by crafty showmen to exploit the credulous; and that the decline of shamanism represents a triumph of reason over irrationality – of science over magic.

Singh argues that shamanism is neither simply primeval wisdom nor superstitious savagery. Rather, shamanism is a complex practice rooted in a human need for agency, explanation and belief in the supernatural. This gave rise to a demand for intermediaries between the human and spirit worlds, forging man’s earliest religion, from which organized religion as we now know it developed.

There is debate about where shamanistic practices originated. Siberia is one suggestion, but they occur across the globe in tribal and hunter-gatherer societies. Apart from healing and divination, a shaman’s services might include changing the weather and boosting businesses. More than this, Singh writes, shamanism is “a compelling technology for dealing with uncertainty,” with shamans acting as “mystical intermediaries who offer security to the insecure.”

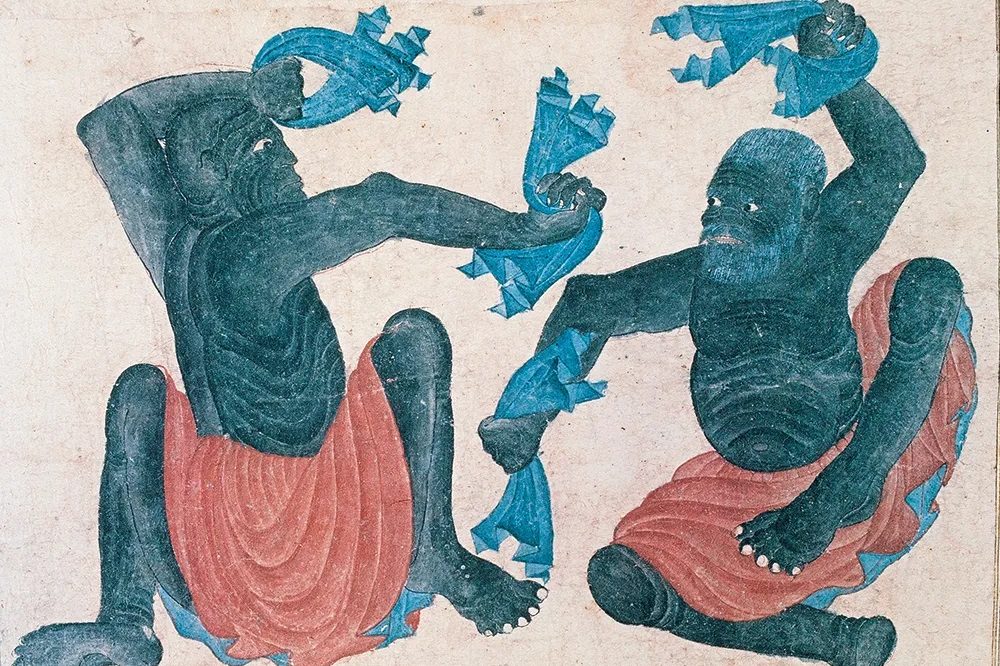

A Mentawai shaman’s services would include healing, divination and raining down afflictions on enemies

This urge to magic is not confined to “primitive” societies. Singh cites a study of major league baseball teams where more than half the players admitted to using pre-match rituals to bring luck, from always eating chicken before a game to always chewing three pieces of gum. One player said he wore the same jockstrap for four years running.

Though the principle is universal, Singh offers a fascinating compendium of shamanistic behavior and techniques, which may differ from one community to another. The Chukchi, a Siberian people native to the Bering Sea region, and Turkic groups in central Asia, summon spirit beings and talk to them. The Yanomami of Venezuela snort a hallucinogenic powder and call upon tiny beings that travel down invisible trails, the males wearing haloes, the females with glittery wands protruding from their vaginas. They are perhaps the ethereal relatives of the “machine elves” singing in a “hyper-dimensional language” that the ethno-botanist Terence McKenna encountered under the influence of DMT. A blind shaman in the Kalahari desert spoke of his eyeballs being kept in a small cloth bag in heaven. When he went into a trance, God descended and placed the eyeballs in their sockets so that a healing could be effected. God then returned them to the bag and took them back to heaven.

While shamans in some societies observe sexual abstinence, it was customary for male Inuit shamans to encourage sexual relations as a form of payment. If women were reluctant to comply, they were sometimes threatened with supernatural consequences, such as becoming pregnant with a seal. We hear of a Sora tribe shaman in India working with an attractive widow and channeling her dead husband, who told her: “I want to sleep with you again, but the only way I can do so is through this shaman’s body.” Ingenious, but hardly ethical.

Performance, ritual, claims of dying and coming back to life and ingesting magical substances are a vital part of the shaman’s work and his perceived authenticity. A shaman who “chitchats” with his audience in an everyday voice might be considered a fraud. One who thrashes violently, speaks strangely and remembers nothing afterwards is more likely to be doing something beyond normal human capabilities. Singh suggests that much of the shaman’s power resides in suggestion – not unlike faith healing. The spells, the spirit journeys, the pig sacrifices, the costumes – all are props to persuade the person haunted by vengeful ghosts that the shaman can heal them.

Elaborating on his theory that shamanistic practices – of being in communion with the spirits – lie at the root of all major religions, Singh points to the Hebrew prophets Samuel, Elisha and “possibly Elijah;” and to St. Paul, too, whose writings abound with references to spirit-inspired powers, rapturous prayer and “signs.” “Early Christians seem to have accessed miraculous powers in inspired states distinct from everyday functioning.” But “Christian exceptionalism” tends to resist the idea of seeing these mystics as shamans, who are cast into the realm of “magic,” whereas prophets belong in the domain of “religion.” “If Jesus had lived in almost any other part of the world, and started almost any other religion,” Singh writes, “we would more readily entertain the possibility of his being a shaman.”

The anthropologist Robin Dunbar has argued that “shamanistic” or “primitive” religions gave way to doctrinal ones. But Singh disagrees, citing the case of Pentecostalism, rich with ecstatic worship, glossolalia and claims of healing. It is “arguably the fastest growing religious movement in the world,” with a combined following approaching 650 million. Shamans did not disappear with the rise of doctrinal authority. Nowadays they lead mega churches, get television deals and proliferate in the murky waters of “wellness.” A survey of the patients of “neo-shamans” in Salt Lake City found that 82 percent described their ailments as depression or “feeling stuck.” A 2021 census on religion in England and Wales revealed that 8,000 people now identify as shamans – judging by online advertisements for “healing centers,” a large proportion of them apparently living in Totnes and Glastonbury. Shamans have become New Age therapists.

Gwyneth Paltrow, of course, has her own “spiritual guide,” Shaman Durek (born Derek Verrett), a bisexual conspiracy theorist described on his website as “a sixth-generation shaman,” and by others as a conman. He is married to Princess Martha Louise of Norway, who claims they shared a past life in ancient Egypt.

Singh writes with a beguiling mixture of erudition and sheer delight in his discoveries. He is also willing to put in the hard yards. In a jungle in the Orinoco basin he is handed a small tray of powder and an inhaler made from the bones of a turkey-like bird called a curassow and snorts up yopo. This is a hallucinogenic snuff compounded mostly of bufotenine, a serotonergic psychedelic similar in structure to DMT and psilocin – and unlike ayahuasca or the San Pedro cactus, it has mostly escaped the “transformative tsunami of psychedelic tourism.”

My muscles felt like they had been blended and were being stimulated with an electric current… Something fractured in my psyche and the observer was separated from the experiencer. As I got down from the chair, I spilled some vomit on my arm. I didn’t care.

At one point, Singh quotes the American psychologist Cristine Legare: “If you want to convince someone of the supernatural, don’t tell them about it. Let them experience it for themselves.”

In connecting the age-old practice of shamanism with today, Singh vividly conveys that we are not so far removed from the Mentawai watching wide-eyed as the sikerei go into a trance, and no less in need of a belief in magic. He urges us to think anew about who and what we are, and just how wide of the mark the “hubris of modernity” may be.

But what of the boy possessed by the crocodile spirit Sikameinan? Sadly, he died. As one of the sikerei explained, his fellow shamans had “messed up the procedure.” Perform the ceremony correctly, he assured Singh, and the boy would have lived. It happens.

Leave a Reply