Rob Henderson is justly famous for coining the phrase “luxury beliefs.” These are opinions which are unshakeably held irrespective of any countervailing evidence, either because the display of such opinions confers status on the holder, or else because adherence to them is an article of faith among some social or professional group in which you need to be seen to belong.

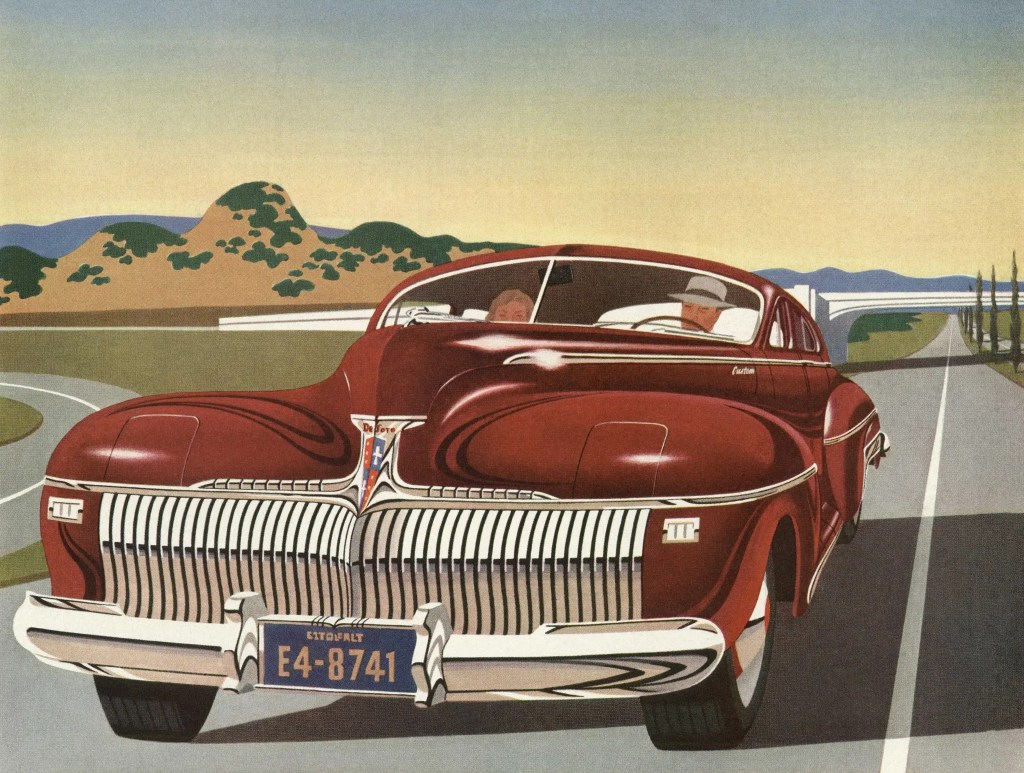

The only approved vision of the future involves extracting people from their cars and cramming them into mass transit

Such beliefs are hence closer to religious creeds than to any conventionally formed opinion. Consequently, any contradiction of such accepted beliefs in public, however intelligent, is treated as heretical: a social gaffe at best, a career-ender at worst.

I once had an idea to host a conference where the speakers and the attendees had all recently retired. The idea was that, freed from the obligation to repeat the usual approved platitudes, you could learn what experts really thought when they were free to speak their minds, rather than reciting a Davos-style litany of received opinion. (My cunning idea was not to pay the speakers, but to hold the event on a cruise ship, which are like catnip for the over-sixties.)

One of the speakers would have been David Metz, the author of Travel Fast or Smart? A Manifesto for an Intelligent Transport Policy, a fabulous polemic written after the author had left his job as chief scientist at the Department for Transport.

The book is a revelation. What becomes clear is that, in policy circles, it is now impossible to express any opinion which is pro-car or in favor of roadbuilding. The only approved vision of the future involves extracting people from their cars and cramming them into some form of mass transit. This is obvious nonsense. While trains and buses are fine for very specific journeys, for the overwhelming number of journeys we make day to day, the car is either irreplaceable, or else supreme. If it’s raining, if you have luggage, if you have children, if you want to transport anything heavier than a suitcase, if you want to travel at an unusual time or anywhere remotely rural, the car or van wins hands down. And I write this as someone who really likes trains.

New roads might be better than rail in countless ways. For one thing, you can build houses alongside them. Indeed, when you take land value into account, the case for road-building becomes stronger still. High-speed rail mostly connects places where land is already expensive with other places where land is also expensive. It is centripetal, funneling people into areas which are already comparatively rich. Roads, by contrast, are centrifugal – they disperse people and their money, adding value to land that was cheap beforehand. If you can capture the increased value of newly accessible land (for instance by selling planning permission) it becomes possible for government to build roads for free while reducing the housing shortage.

But, Metz explains, expenditure on transport infrastructure is not based on land value. Instead, it is accounted for by a fatuous model of ‘time saving’. This has the unfortunate side-effect of valuing the time of rich people more highly than that of poorer people, which is why southern England receives disproportionately more funds than the north. This time saving model is moronic. The value of infrastructure investment arises because people go to more places, not because they go to the same places faster.

Hence the case for a large program of road-building to feed economic growth is immense – yet unsayable. A luxury belief has made it impossible in policy circles to promote cars or roads. Like all luxuries, this belief is costly. For the price of HS2, you could have bought all 300,000 people who travel regularly between London and Manchester a new Rolls-Royce Spectre. I don’t think anyone would have complained.

Leave a Reply