Modern popes, for better or for worse, tend to be defined in soundbites.

John Paul II’s clarion call of “Be not afraid” became emblematic of his invitation to young Catholics to embrace their faith and his rallying of the West against the specter of international communism. Benedict XVI’s great theological career, and his term as a pope in the model of priest and professor, remains summed up in his simple declaration that Deus caritas est. For Francis, the world will likely remember, in the immediate weeks after his death anyway, his often quoted, though often misrepresented, motto of “who am I to judge?”

Uttered during one of his habitual in-flight press conferences in response to a question about gay clergy who sought to live their ministry and their lives faithful to the Church’s teaching on human sexuality, it became a shorthand for a pope committed more than anything to a radical posture of welcome – a “Vatican Council II pope,” he was dubbed in the media, dedicated to throwing open wide the Church’s doors to Catholics, and indeed to everyone, without censure or reservation about their complicated lives.

But if that is how the world saw Francis, those living with and within the bubble of the daily life of the world’s largest Church will remember a different kind of pope – a contradictory and mercurial pontiff who often appeared less like a sure helmsman of the bark of St. Peter and more like a man struggling to ride a horse bolting in several directions at once.

Few now remember that when he stepped onto the famous balcony over St. Peter’s Square in 2013, he emerged as a pope elected with a clear mandate, not to renew the faith but to reform a Vatican plagued by scandal and corruption.

By that measure, his legacy is easy to see, though harder to sum up.

Francis instituted wave after wave of financial and legal reform at the Vatican, while visibly turning on his own reformers, such that he reigned to see both the conviction of Cardinal Angelo Becciu, his former chief of staff, for financial crimes related to a London property scandal, and also the public defenestration of Libero Milone, the auditor who caught him.

If overt criminality in the Vatican is now much reduced, the Holy See is closer than ever to a full-blown liquidity crisis, if not actual bankruptcy.

For a pope who often railed against “doctors of the law,” he ironically proved to be one of the most prolific papal legislators in recent history – redrafting the Vatican constitution and revising the entire internal penal code of the Church. At the same time, he showed himself to be a confirmed scofflaw, often ignoring his own major legislative changes on matters as petty as the election of largely ceremonial positions, like the dean of the College of Cardinals, or as major as the prosecution of favored bishops when they were accused of sexually abusing their own clergy.

Major sexual abuse scandals involving bishops and cardinals led to a global summit and landmark legislation in 2019 – yet few of the new rules and none of the promises of transparency were brought to bear when friends of Francis, like Argentine Bishop Oscar Zanchetta, found themselves indicted for crimes of abuse.

For those – and they were many – who expected Francis to be the pope to break with centuries of Church teaching on issues like gay relationships or the role of women in the hierarchy, he proved himself an equally dramatic actor but unreliable figure.

In 2023 his doctrinal department published, to global headlines, authorization for the blessing of gay couples, only to then spend weeks walking it back, variously insisting that nothing had changed, that gay people could be blessed but never their unions, and that the entire Church in Africa had been granted an opt-out of the entire issue.

During his signature legacy project, a global, multi-year synod meant to usher in – as the saying always has it – “a new way of being Church,” Francis insisted that issues like women’s ordination and married priests were not up for discussion, while pointedly entrusting the project to some of the most vocal advocates for those causes.

While often invoking the sense of Vatican Council II’s call for a more global, decentralized way of “being Church,” Francis proved himself to be an often obsessive micro-manager, allowing his Vatican to police local parish weekly bulletins for the wrong (too traditional) kind of liturgy.

And while Francis preached a vision of synodality, consultation, and collegiality, he showed himself willing to depose bishops from all corners of the world – seemingly on a whim, without due process and sometimes without any reasons given – if they were considered ideologically out of step with him.

Francis’s most favorable interpreters, myself among them, have long seen in him a pope with a great personal touch and an almost preternatural ability to communicate with the world on an emotional level. The hope and theory was his pontificate would, in the final reckoning, be appreciated as a time of re-scoring, rather than revolution – of setting the lyrics of the Church’s teachings to new music and new rhythms.

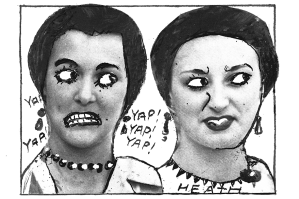

Instead, he penned not a new symphony but a violent cacophony, leaving behind him a Church more divided – geographically, theologically, and liturgically – than it has been in decades, and a Vatican teetering on the brink of insolvency.

Many might insist that it is too soon to judge the legacy of the man who himself famously withheld judgment. But others might recall his words in Paraguay in 2015, when he enjoined the crowd to “Make a mess, but then also help to tidy it up.”

In his nearly 12 years as pope, Francis certainly made a mess. It’s now for someone else to help tidy it up.

Leave a Reply