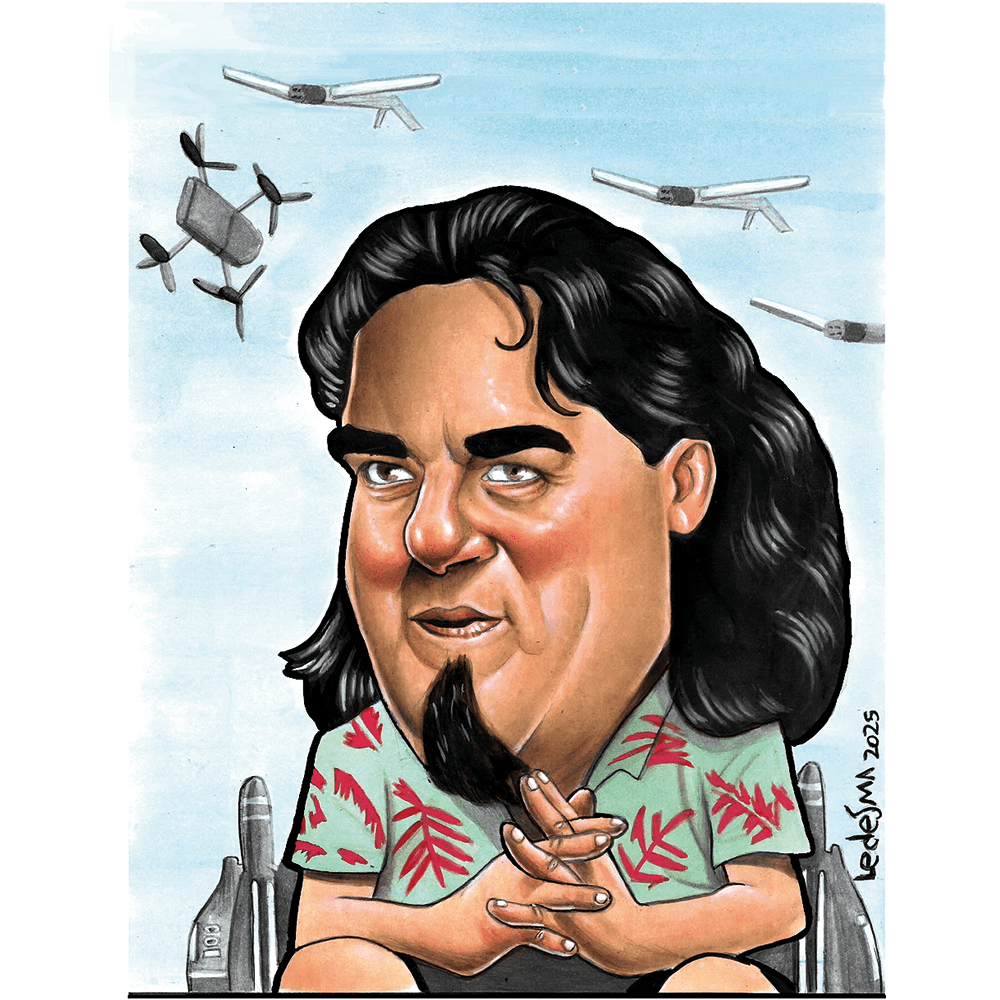

Defense contractors tend, on the whole, to be a pretty faceless crew, indistinguishable in their dark suits and hence little known to the world outside the military-industrial complex. Palmer Luckey, founder of Anduril Industries, strives to be different, invariably sporting a uniform of Hawaiian shirts, shorts and flip-flops – projecting an iconoclastic image attractive to venture-capital investors, somewhat in the manner of former crypto mogul Sam Bankman-Fried.

He beguiles journalists with exciting monologues about the great things his vision can accomplish for US defense, making him, according to a glowing profile in the Financial Times, “arguably the most crucial figure bringing Silicon Valley to the front lines of American national security.”

A more recent review in the Wall Street Journal described him as “one of the brightest examples of a new wave of ascendant entrepreneurs.” It continues: “They eschew what has made Silicon Valley so powerful – personal gadgets and ad-tech – and pour themselves into super hard and sometimes controversial sciences and engineering they say can make America better: Supersonic airplanes. Nuclear energy. Space travel.”

Luckey’s visions for the future battlefield include an “AI-powered sensor fusion platform” to “build a perfect 3D model of everything that’s going on in a large area.” Soldiers in the future, he predicted confidently to a wide-eyed CNN interviewer in 2017, will be “superheroes’’ with “the power of perfect omniscience over their area of operations, where they know where every single enemy is, where every friend is, where every asset is.”

The virtual reality headset, Oculus, that Luckey developed and sold to Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta for $2 billion by the time he was 21 helped propel what had formerly been Facebook into a $36 billion spending binge on virtual reality that ultimately yielded little in the way of revenues. But by the time Zuckerberg lost interest in the project, Luckey had already left Meta, pushed out in 2016 – supposedly thanks to the news that he had donated to Donald Trump which thereby shocked the management’s then-liberal biases.

There may be more to the story than that. Luckey himself refers darkly in his freewheeling blog to “getting run out of Silicon Valley by backstabbing snakes.” In any event, he has continued to declare unremitting loyalty to Trump and corresponds regularly with his pen pal, Elon Musk. He also just happens to be the brother of Ginger, who is married to the former congressman Matt Gaetz – Trump 2.0’s first choice for attorney general.

In 2017, Luckey co-founded Anduril with support from Peter Thiel, the right-wing and hugely wealthy tech entrepreneur who, according to his biographer, has been determined “to bring the military-industrial complex back to Silicon Valley, with his own companies at its very center.”

Anduril’s first pickings from the national security treasure chest came in the form of border surveillance contracts, but the age of AI was dawning, and Anduril stands at trade shows were soon bristling with artfully displayed models of systems promising to address every need on the battlefield – small drones, large drones, anti-drone drones, reusable drones, underwater drones, all endowed with the miracles of Anduril’s in-house Lattice “all-domain” command and control system.

Free of the embarrassments of over-priced and underperforming programs that burden the record of legacy defense giants such as Lockheed Martin or Boeing, Anduril appears to represent all that is new and different in a world of warfare dominated by drones and artificial intelligence.

The message is apparently falling on fertile ground. This year alone, Anduril has taken over a US Army contract, potentially worth some $22 billion, to develop an “augmented reality” headset for soldiers on the battlefield; the US Marines have agreed to a deal for an anti-drone defense system potentially worth $642 million; the UK defense ministry has signed to buy £30 million worth of Anduril drones on behalf of the Ukrainians.

In January, the company announced plans to build a 5 million square foot factory in Pickaway County, Ohio, to be known as “Arsenal-1.” The plant will build the Fury, an autonomous drone, in contention for an enormous Air Force contract to build “collaborative combat aircraft” – fighter drones that will fly in conjunction with a manned aircraft but operate autonomously.

Not everyone is impressed. “Anduril is the Theranos of defense,” declared C. Mark Brinkley, a representative of General Atomics (a rival contender for the Air Force contract), as he gazed darkly at a life-size model of the Anduril offering, originally designed to be merely a target drone, on display at a trade show last October.

This was a harsh slur, Theranos being the Silicon Valley start-up that raised millions on the fraudulent claim that it could perform complex diagnostics from a simple drop of blood, eventually earning an 11-year jail term for its founder Elizabeth Holmes. “Quite frankly, when you look at the Fury – to me, it looks like trying to use a drop of blood to change the world,” continued the baleful Brinkley, heaping scornful attention on the bulging air-intake scoop underneath the Fury’s belly, suggesting that this left no room for interior weapons storage or even landing gear.

“Guess I am going to prison for 11 years,” mocked Luckey in response. (This sort of talk, at least in private, is not unprecedented in the industry; a senior executive of one giant defense contractor once assured me that an equally large rival was in fact owned by the Mafia.)

Others have raised questions about Anduril’s own videos of its weapons in action on the test range, pointing unkindly to the apparent absence of dust kicked up by a drone’s engines in one as it descends neatly on to a desert floor, or the obvious aids enabling an autonomous weapon to find and hit a target in an Army testing ground.

A more positive assessment comes from a military professional who has had the opportunity to assess Anduril hardware. He found them “very effective” but stressed to me that they are “incredibly expensive.” Cruelly, he compared them to the notoriously over-budget and complex F-35 fighter, affordable only in limited quantities. “We should buy the cheapest, $350 to $500 a piece, not $250,000 or half a million for one shot, one kill.”

Whether or not Fury is successful in the competition for the collaborative combat aircraft contract, the program for the “augmented reality” Army system recently acquired from Microsoft caters to Luckey’s deepest enthusiasm: the dream of creating a “superhero” soldier endowed with a video-game headset feeding him a plethora of information about what is going on around him such as, hopefully, enemy soldiers otherwise concealed behind buildings or bushes.

The Integrated Visual Augmentation System, blogged Luckey, marks “the beginnings of a new path in human augmentation, one that will allow America’s warfighters to surpass the limitations of human form and cognition, seamlessly teaming enhanced humans with large packs of robotic and biologic teammates.”

Microsoft has been trying to achieve this for several years, using a virtual reality headset that proved commercially disappointing. Soldiers chosen to test what they called “magic goggles” did not report happy results. According to a 2023 report from the Pentagon’s chief testing officer, they complained of “disorientation, dizziness, eyestrain, headaches, motion sickness and nausea, neck strain and tunnel vision” as well as “inability to distinguish friend from foe, difficulty shooting, physical impairments and limited peripheral vision.” Luckey will doubtless claim success in overcoming these and other problems, especially as Anduril, currently valued at $14 billion thanks to healthy infusions of venture capital cash on the promise of potentially large Pentagon contracts, is likely to go public in the not-too-distant future.

But it will be difficult to know for sure, given the company’s reluctance to supply verifiable information on the actual performance of its products, either in independent tests or on the Ukrainian battlefield. Despite unsourced claims in the defense trade press that an Anduril autonomous drone, Ghost-X, has been used by the Ukrainians since early in the war, no supportive evidence has surfaced. A company spokesman declined to comment on grounds of “operational security.” The list of weapons supplied to date by the US to Ukraine, as itemized by the State Department, makes no mention of any Anduril products.

The notion of light-footed entrepreneurs spawned in the fast-moving world of Silicon Valley is attractive, certainly to an administration laced with Valley alumni – Musk being the most prominent example. Anduril and others promise a fighting force endowed with swarms of drones and artificial intelligence, citing the ongoing drone war in Ukraine as the shape of things to come.

Luckey himself draws inspiration from science-fiction writer Robert Heinlein’s 1959 militarist fantasy Starship Troopers. But as tech companies muscle their way to prominent perches in the military-industrial complex, it’s beginning to look as if they are inexorably adopting the customs and practices of the venerable behemoths already in situ – Anduril’s “incredibly expensive” drones being a case in point.

The revolving door between Pentagon offices and the new entrants’ executive suites is already whirling; senior Anduril executive Michael Obadal is moving to the powerful post of Army under-secretary, while alumni of Thiel’s Palantir are already well ensconced in the government’s defense complex, and vice versa. Those Hawaiian shirts will quite certainly turn out to be incredibly expensive.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply