Anne Frank died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen in late February 1944. Her last days were spent in the sick barracks caring for her sister Margot, who had a high fever and smiled contentedly, her mind already wandering. Anne, too, had been feverish, but “friendly and sweet,” according to witnesses. Her last recorded words were: “Margot will sleep well, and when she sleeps I won’t need to get up again.”

Ruth Franklin’s superb and subtle book pivots around this moment, which is described in the starkly titled central chapter, “Corpse.” Half her study tells Anne’s story up to the tragedy of her death. It traces her parents’ backgrounds and characters, her birth in Germany, the family’s flight to the Netherlands, their going into hiding, the writing of the diary, the betrayal and arrest, Anne’s time in Auschwitz and her final days in Bergen-Belsen.

The second half of the book, which is equally fascinating, examines what happened afterwards, starting with Otto Frank first reading his daughter’s papers, the editing process and publication, and then Anne’s rapid rise to international prominence as the most famous victim of the Holocaust. Franklin looks at depictions of Anne in plays, films and books and at the use and abuse of her name and story for political purposes. There is now a small industry of Anne Frank scholarship, but a good case could be made for this book’s being the definitive work on the subject. It is highly recommended.

Otto, one of the heroes of the study, was born in Frankfurt in 1889, less than a month after Adolf Hitler. His father owned a bank and the family had a box at the opera and a large house where they entertained in style and held costume balls. Otto learned the cello and traveled to America. In August 1915, he joined the army and served with distinction as an officer. After the war, the family bank foundered, partly because of a patriotic over-investment in war bonds, but even so the Franks were well off. Otto married Edith, also wealthy and from a family that kept kosher. Otto, by contrast, did not have a bar mitzvah and never learned to read or speak Hebrew.

Annelies Marie – her full name – was born on June 12, 1929, three years after her sister. The two girls were very different. Margot was sporty, quiet, obedient and always successful in school. Anne was physically frail, a chatterbox, easily distracted, flirty and creative. Only their early years were spent in Germany. Otto and Edith were wise to the dangers of Nazism and in 1934, soon after Hitler came to power, they moved to the Netherlands, where they set up a pleasant but much more modest home.

The family were happy in Amsterdam, but Franklin also chronicles their growing awareness that even there wasn’t safe. Desperate attempts were made to secure first an American and then a Cuban set of visas. These, however, were not forthcoming, even for considerable sums. In May 1940 Hitler invaded the Netherlands. At first, little happened, but by 1942 anti-Jewish measures had intensified and by the summer a full programme of deportation to the death camps in the east began. On 6 July 1942 the Franks – ever prepared – went into hiding as part of a group of eight.

Anne’s years in the secret annexe will be familiar to readers from her diary. What is less well known, and excellently described by Franklin, is the way in which the diary came into being. There was, in fact, no single document. Anne was given a notebook with a red-and-white checked cover on her 13th birthday. Her first entry, penned alongside a photograph she’d pasted in, was made that day:

Gorgeous photograph isn’t it!!!!

I hope I shall be able to confide in you completely, as I have never been able to do in anyone before, and I hope that you will be a great support and comfort to me.

The entry beneath this, again of two sentences, is dated September 28, 1942, more than three months later, and is followed by a list of “the seven or 12 beautiful features (not mine mind you!)” starting with “1. Blue eyes, black hair. (No).” The entry below that jumps back in time, dated June 14.

So the first notebook is highly erratic. Entries appear on random pages and only ten in total are written between June and September 1942. Some of these, but not all, are in diary format. After September, many of the entries are transcribed letters, a few of them real, others to invented characters such as Loutje, Pien and Pop. The notebook also contains some practice at shorthand, various comments on stuck-in photographs and a neatly written out alphabet.

In all, Anne filled four notebooks during her time in hiding, but one of these has been lost. By 1944 she had become a regular diarist, beginning entries “Dear Kitty,” the salutation to an imaginary friend and confidante that is now known to millions.

She chronicled her love affair with Peter van Pels, her rows with her mother, the hardships of existence in the annexe, her hopes for life in the future, her constant fear of being discovered. These notebooks, which run from June 12, 1942 to August 1, 1944, are collectively known to scholars as Version A.

In the spring of 1944, however, Anne heard a broadcast on Allied radio in which a Dutch minister in exile suggested that after the war there would be a need for a record – in the form of diaries and letters – of the Dutch experience of occupation. Diaries, he said, might be published. This inspired Anne, and as a result she quickly began work on a novel, The Secret Annexe, written on carbon paper and based on the record she had kept in her notebooks. It reads like a diary and is highly autobiographical, but it uses pseudonyms, and the episodes in it are reconstructed from memory and research. It is known as Version B.

On August 4, 1944 the annexe was discovered and the eight occupants arrested. Anne’s papers – Version A, Version B and various other bits of fiction and non-fiction – were left behind. Not until Otto returned from Auschwitz on June 3, 1945 – the group’s sole survivor – did anyone read them.

The second half of Franklin’s book tells the story of how those loose, disordered papers were transformed into The Diary of a Young Girl and how the book became a worldwide phenomenon. Otto read Version A and Version B in floods of tears, overcome by his daughter’s ambition to be a writer. He consulted experts and publishers and finally created a fusion of the two versions, inventing nothing but brilliantly splicing and cutting. This is known as Version C. It blended the younger, flighty Anne of Version A with the more earnest, authorial girl of Version B.

It also removed some of the criticism of Edith and a few of the more explicit sexual passages. Today, readers are most likely to encounter the full, unexpurgated, expanded version of Otto’s creation, known as Version D.

At first, there was only modest interest in the book. The British publishers soon withdrew it after poor sales. But in America, where Eleanor Roosevelt agreed to put her name to a preface, it soon became a bestseller. Published on June 16, 1952, the first print run sold out before the end of the day. A second print run of 15,000 copies sold out in a week, and a third, of 25,000, was ordered. Within months, there were plans for a play and Hollywood film.

Franklin examines the conflicts around Anne as her fame grew exponentially. There was a court case over the play, with the writers accused of plagiarism by a rival playwright, Meyer Levin, who also felt that the Jewishness of Anne had been minimized to ensure success on the stage. Levin claimed that the Anne of the play and the subsequent film had been made “universal” and therefore inauthentic. There was another trial regarding the diary’s authenticity and many rows over portrayals of Anne that appeared in novels. Was she a lesbian? Was she a spokesperson for all the oppressed, or only for a specific Jewish experience?

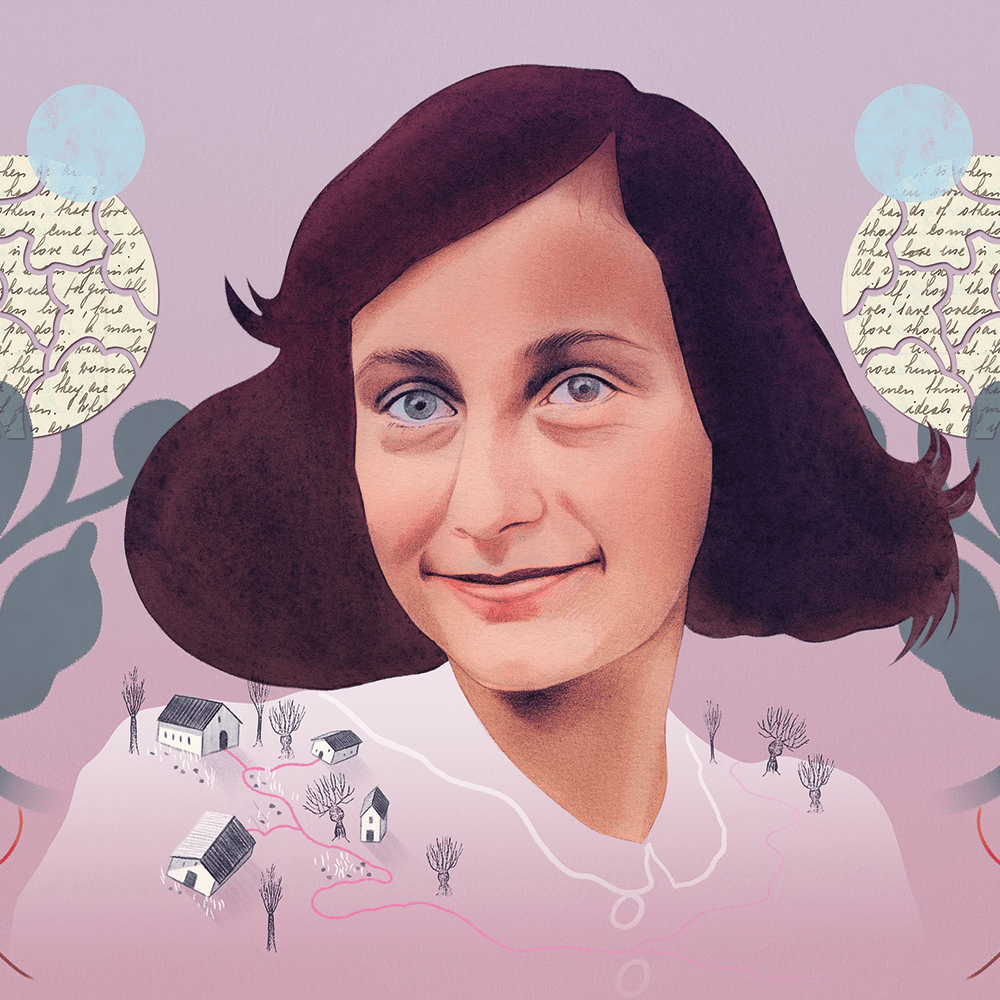

To date, The Diary of a Young Girl has sold more than 30 million copies in 70-odd languages. The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam is always booked to capacity and has nearly 1.3 million visitors a year. The author’s photograph is so well known it has been compared with the Mona Lisa. This book does a brilliant job of accounting for that phenomenon. Franklin writes with enormous intelligence about the many “cultural products” that have grown from Anne’s legacy and, just as importantly, she gives us a human, sympathetic and honest picture of the girl herself. Anne would be 95 now, had she survived the war and lived that long. As it is, thanks to her father and her own genius, she has achieved a kind of immortality.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply