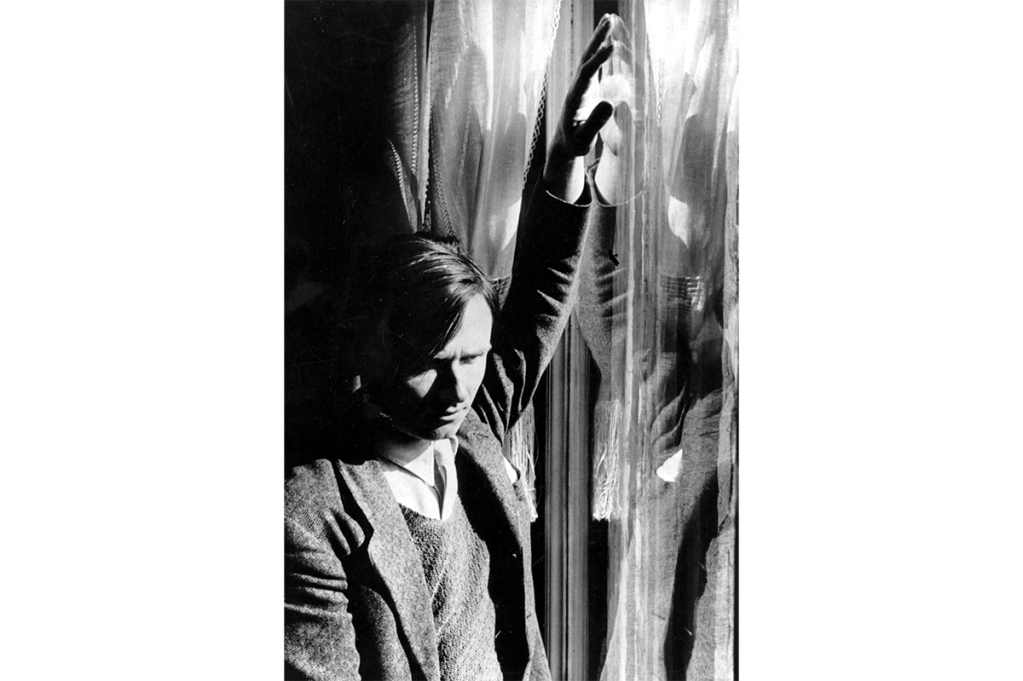

In the late 1930s, the author W. Somerset Maugham said that Christopher Isherwood “holds the future of the English novel in his hands.” But the younger writer was about to leave London for Los Angeles. He and his close friend W.H. Auden emigrated in January 1939. En route, their ship was beset by a blizzard. It arrived in New York looking like a wedding cake, in Isherwood’s evocative description.

Their journey to the New World was a wholescale rejection of what Isherwood had long thought of as “the Test.” For earlier generations, this had been the Great War (Isherwood’s father, Frank, was killed at the Battle of Ypres). For them, it was to be World War Two. Auden and Isherwood would be damned as cowards, but Isherwood had already found other interests. He was a full-blown pacifist because of his Hinduism and wanted to become a Hollywood screenwriter. During his American sojourn, he would discover other challenges, too. His artistic integrity would be compromised by his money troubles, and even though he had escaped from the homophobia of Britain, life in a more anonymous city on the West Coast would have its own fair share of strictures and difficulties, too.

Isherwood has long been regarded as less interesting than Auden, perhaps unfairly so. Yet two recent biographies, Katherine Bucknell’s epic Christopher Isherwood Inside Out and Jake Poller’s shorter Christopher Isherwood, meet a lately renewed interest in his life and work. Bucknell’s much longer book moves into psychobiography territory, finding unconscious self-punishments and repetitions. This often verges on the contrived. She writes, for instance, that when Christopher suffered a strange sickness as his father Frank was about to die in Belgium, he was “channeling his father’s destiny.” Perhaps, perhaps not. She also presents each of his relationships as having strange and convoluted connections with his childhood; we learn that a boyfriend’s white Fiat is an “incarnation of the mail cart (also white) in which [his mother] Kathleen and Nanny had pushed the infant Christopher around the Cheshire countryside.” Some readers may not be entirely convinced.

Still, if Bucknell’s theories sound overly mystical, this is perhaps appropriate to the subject. The idea of “incarnation” is a pervasive metaphor throughout Isherwood’s life. Poller’s approach is simpler. He argues that many of Isherwood’s more esoteric decisions represent self-conscious rejections of Kathleen’s Edwardian attitudes. Certainly, he takes a tougher line than Bucknell on Isherwood’s departure from England, rejecting his explanation that he was moving to meet the “future of English culture,” rather than avoiding conscription. Still, this potentially interesting avenue is barely explored, as Poller’s far shorter book gives equal weight to the life and the work. Poller views Isherwood’s writing as early examples of autofiction, and suggests that, at his best, the author blended the traditions of realism and the confessional into a fascinating whole, meaning that even his diaries and memoirs cannot be taken as literal fact. When he arrived at Los Angeles, Isherwood was focused on the Hindu philosophical idea of Vedanta. He even trained at a monastery in Hollywood: the conflicts of Europe seemed very far away. When he did publish another novel, 1945’s Prater Violet, it was a masterful work that was influenced by his newfound faith. If there was a dichotomy between the demands of his religion, which asked for the sublimation of personal identity, and the requirements of his work, which needed “Christopher Isherwood” to be on the books that he wished to sell, the latter was always going to win out.

He left the monastery and embarked on a relationship with a somewhat wild man named Bill Caskey, which did not make for a fruitful literary collaboration. He published no novels for nine years until The World in the Evening came out in 1954, by which time he had met Don Bachardy, an LA native 30 years his junior, with whom he would settle in Santa Monica Canyon until the end of his life in 1986.

Bachardy was a portrait artist who illustrated some of Isherwood’s dustjackets, and their relationship was sometimes beset by rivalry, both romantic and professional. However, they collaborated on film scripts, and Bachardy gave important and useful responses to Isherwood’s manuscripts. They became involved in a community of artists, actors, and other writers, as Isherwood taught at Los Angeles State College, and wrote some mostly forgotten novels – with one major exception – before officially retiring from his literary career with two autobiographical titles, one about his parents, Kathleen and Frank, and one on gay life in the 1930s, Christopher and his Kind.

That exception, 1964’s A Single Man, is probably Isherwood’s most popular work besides the Berlin books, not least because the Tom Ford-directed, Colin Firth-starring 2009 adaptation brought considerable attention to the novel. Inspired by a reread of Mrs. Dalloway, Isherwood restricted himself to a story set over the course of a day, beginning and ending in a small house in Santa Monica. English expat George, a professor at San Tomas State College, mourns his boyfriend Jim, who has recently died in a car crash, but later that day meets someone new. Auden, who thought the comparison the novel makes between homosexuals and Jews was strained, nonetheless commended it via telegram as “BY FAR THE BEST THING YOU HAVE DONE.” Many have agreed with him. The spiritualism that was still unformed in Prater Violet becomes more explicit in A Single Man’s ending, which pictures its characters as rock pools on the California coast, subsumed by the Pacific tide as they sleep:

But do they ever bring back, when the daytime of the ebb returns, any kind of catch with them? Can they tell us, in any manner, about their journey? Is there, indeed, anything for them to tell –except that the waters of the ocean are not really other than the waters of the pool?

In this novella, Isherwood presented every facet of himself on the page: a respected and sharp-tongued wit, if sometimes a drunk, befuddled and angry one; a man who lived with men; a member of an old English family who went West and found his mystical East. Somehow, these all became facets of the eponymous single man.

Poller and Bucknell have a considerable task on their hands when it comes to making a serious case for Isherwood’s rehabilitation, and each approaches him in different ways.

The now 90-year-old Bachardy was the major source for Bucknell’s book, and the second half of Christopher Isherwood Inside Out understandably reads like a double biography, giving as much attention to Bachardy’s professional progress and his time in London as to Isherwood’s later years.

Her book is very sympathetic, refusing to offer moral judgment on Isherwood’s decision to leave England or some of the more scabrous passages in his diaries. Instead, through her insights, personal determination and artistic discernment emerge as Isherwood’s redeeming qualities, whether he is producing his own work, poring over his past, or supporting Auden’s or Bachardy’s artistic efforts.

Bucknell’s book is also a considerable feat of research that majors in the many apparent connections between the life and the work, which itself informs Poller’s notion of autofiction as key to understanding his subject. Isherwood’s was an eventful and varied life, and so became the source material for his writing, whether presented as fiction or not.

Poller is strong on the real-life basis of the events that make up the novels Goodbye to Berlin, Prater Violet and A Single Man, while describing the three volumes of diaries, which Bucknell edited, as nothing less than Isherwood’s Remembrance of Things Past. He writes, affectionately, that they “add up to a monumental life.”

Auden wrote of W.B. Yeats that “he became his admirers.” Something similar could be said of these biographies. The lives of writers, lived self-consciously with an eye to posterity, often make them their own best subjects and wise biographers – which both Bucknell and Poller undoubtedly are – know how to tease out nuance, contradiction and insight.

The complex life of Christopher Isherwood is now an open book, and it makes for an excellent read.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply