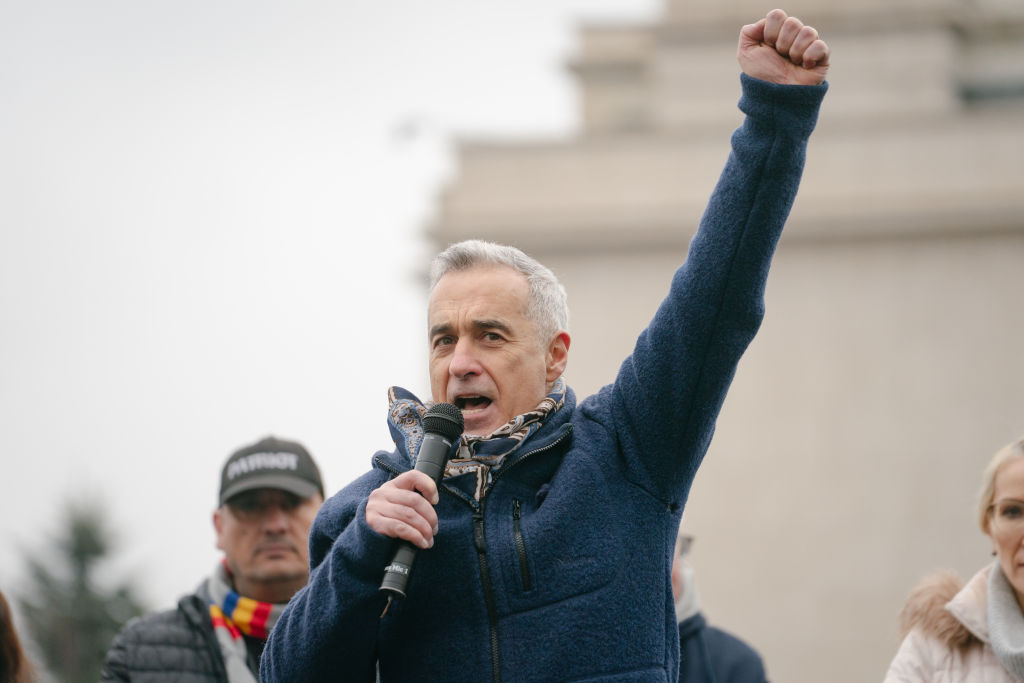

Violence broke out in Bucharest on Sunday evening after Romania’s Central Electoral Bureau disqualified Cǎlin Georgescu from running in May’s re-run presidential election. In a statement, the bureau justified its decision to exclude Georgescu on the grounds that his candidacy “doesn’t meet the conditions of legality” because he “violated the very obligation to defend democracy.”

Supporters of Georgescu, whom the BBC has described as a “far-right, pro-Russia candidate,” gathered outside the Central Electoral Bureau to express their outrage and soon clashed with police.

Until six months ago, Georgescu’s name was virtually unknown outside Romania. Then, the 62-year-old surged to victory in the first round of November’s presidential election, a result that stunned Europe’s political establishment.

This alarm grew as opinion polls indicated Georgescu would win the second round. Something had to be done — and it was. Just days before the decisive vote, Romania’s Constitutional Court annulled the first round, citing alleged Russian interference. The court had reviewed some declassified intelligence documents claiming that 800 TikTok accounts had been activated shortly before polls opened. While there was no evidence of voting irregularities in the election itself, the fact that Russia had been active on social media was enough for the court to intervene.

At the time, Georgescu compared himself to Donald Trump — an anti-establishment candidate targeted by what he called Establishment “lawfare.” The Trump administration has since pointed to Georgescu as an example of the EU’s creeping illiberalism.

In a speech at last month’s Munich Security Conference, Vice President J.D. Vance expressed his shock “that a former European commissioner went on television recently and sounded delighted that the Romanian government had just annulled an entire election… these cavalier statements are shocking to American ears.”

The commissioner in question was Frenchman Thierry Breton, who, in a television interview in January, boasted, “We did it in Romania, and we will obviously do it in Germany if necessary.” He was referring to the upcoming German election and the possibility that the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) might win.

As it turned out, simply annulling Romania’s presidential election didn’t slow the Georgescu movement. Quite the opposite — he gained momentum, and polls showed he would win by a landslide in May’s re-run election. As I predicted in January, Romania’s elite wouldn’t let that happen.

And they didn’t. At the end of February, Georgescu was detained by police while driving through Bucharest to file his candidacy for the election. He was indicted on six counts, including false funding sources and providing false information in his previous campaign. He was also barred from leaving the country and from creating any new social media accounts.

Now, he has been officially disqualified from running for president — a decision he has called a “direct blow to the heart of democracy worldwide.”

The AfD didn’t perform as poorly as Thierry Breton had feared in Germany — they came in second, winning 20 percent of the vote, just eight percent behind the center-right CDU.

But the CDU quickly ruled out inviting the AfD to join its coalition government. Instead, they are in talks with the Social Democrats — an odd reward for a party that, in finishing third, recorded its worst election performance since 1945. Alice Weidel, co-leader of the AfD, called the snub “undemocratic… you cannot exclude millions of voters per se.”

Something similar happened in Austria. The anti-immigration Freedom Party actually won last October’s election, yet they won’t be part of the newly formed coalition government because the Conservative People’s Party, the Social Democrats, and the liberal Neos refuse to work with them. The Freedom Party’s leader, Herbert Kickl, called the alliance a coalition “of losers.”

In just a few months, the votes of millions of Romanians, Germans and Austrians have been discarded by Europe’s political elite.

And it may not stop there. At the end of this month, Marine Le Pen will learn whether her political career is over. Last fall, the leader of France’s National Rally stood trial in Paris, accused of misusing EU funds. Prosecutors have demanded that she be barred from running for office for five years. The verdict will be delivered on March 31. Le Pen says she is the victim of “unbearable political interference in the democratic process.”

She’s not the only one in an increasingly illiberal Europe.

Leave a Reply