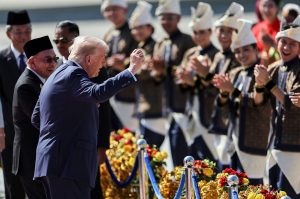

Few critics ever analyzed why Trump’s appearance and comportment resonated with his base and intrigued neutrals who otherwise might have been repelled by his agenda and personal history. American men in their sixties and seventies often do strange things to retain their youth and vibrancy. They can dye their hair, tan their skin, remove their wrinkles, or substitute loud clothes for a declining physique. Trump did all that and more. He appeared loutish to the Beltway establishment. But unlike aging Hollywood celebrities, he became more rather than less resonant and empathetic to the middle class for the strained effort, as if proof that even aging billionaires were patched together creaky everymen and insecure humans after all. Trump did not put on Beltway politicians’ customary flannel shirts and jeans at state fairs or farm shows, but showed up out of place but nonetheless unadulterated and authentic with his trademark baggy suit and loud, long tie.

Most Americans in 2015–16 also did not quite know, and did not care, where Trump’s odd accent came from. But they grasped that it was certainly not Washingtonian.

Trump’s grammar and diction were also not schizophrenic like those of suburban politicians of the Clinton or Obama sort. Trump never faked a black patois when speaking to minorities or tried on corny homespun drawls when campaigning in bowling alleys or state fairs. Trump sounded lowbrow all the time to all the people. Thereby, he came across as transparent and regular, as if a Georgia farmer would rather hear a Queens accent than Hillary Clinton struggle with ‘y’all.’

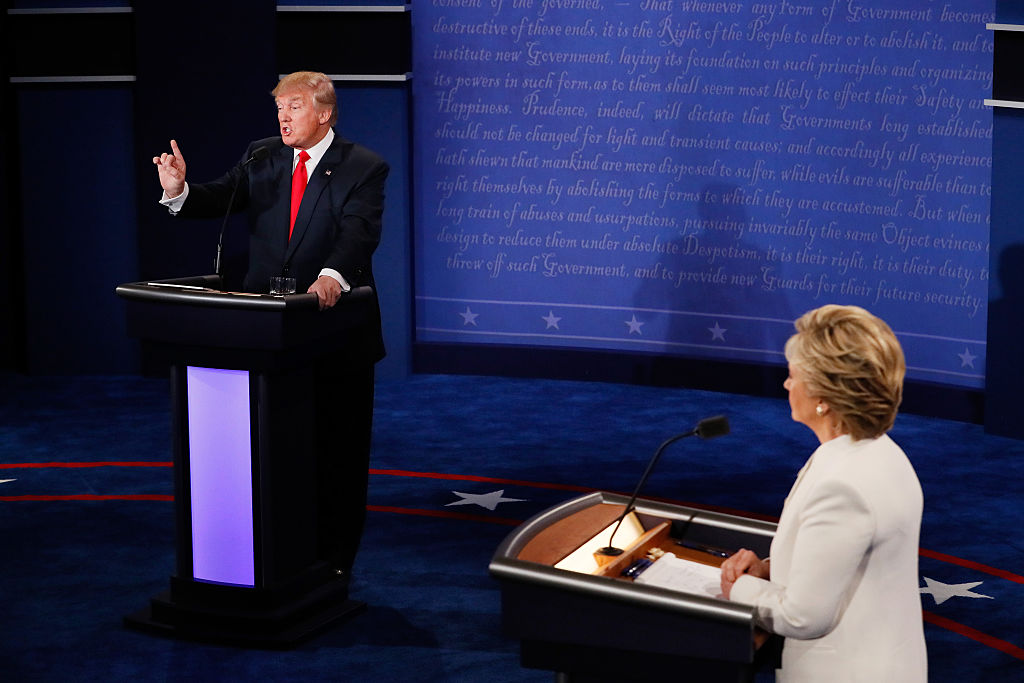

It is difficult to tell to what degree some of Trump’s outrageousness was scripted. As a student of popular culture, he might have known that viewers of the 1980 comedy hit film Caddyshack overwhelmingly rooted for the obnoxious and crude — and transparent — party crasher Al Czervik (Rodney Dangerfield). In the now cult movie, Czervik was far more empathetic than his well-groomed archnemesis and habitually outraged Judge Elihu Smails (Ted Knight), the smarmy keeper of country club protocols and standards. In some sense, Trump and Clinton replayed those respective roles in the 2016 election.

Trump’s appearance and diction played some part in his appeal to red-state and purple-state middle-class voters. Both empowered Trump’s message, at least as calibrated by his base supporters. By nature, they were contrarians and again enjoyed the outrage of the perceived establishment that Trump ignited. And of course, Trump did not exist in a vacuum, but offered a choice between someone and something else…

How strange that Democrats during the primary were worried that Hillary Clinton was the only candidate who could win the presidency, while Republicans were equally convinced that Donald Trump was the only one of their own who could lose the general election. More likely, any major Democratic figure other than Clinton might have won, and all other Republicans other than Trump might have likely lost.

Yet if the Republicans were to nominate Donald Trump, then the sins of Hillary Clinton uniquely would cancel out his own. And if Trump were to run as the fresh outsider sent in to drain the swamp, then Clinton was the most likely among Democrats to represent the tired landlord of the miasma.

If Trump seemed too old and unfit, then Clinton all the more so. And if rumors of Russians tainted Trump’s campaign, then they were predated by Russian operatives angling with the Clintons throughout Hillary’s government service. In some sense, Hillary Clinton created the Trump presidency.

So aside from Trump’s contentions that the United States was in decline and that only if Americans elected him could this regression be arrested, there was the matter of Hillary Clinton, his 2016 campaign opponent — and by July the only impediment between Trump and the presidency.

Trump certainly campaigned on issues. We have seen that he embraced existential themes and concrete wedge issues. And he had a divided and volatile electorate to leverage further. But Trump also had the controversial opponent Hillary Clinton, or rather the explicit argument that whatever Trump was, he certainly was not Hillary Clinton. The two were certainly a pair of contradictions in almost every aspect.

Physically, Trump’s bulk fueled a monstrous energy; Hillary’s girth sapped her strength. The reckless Trump did not drink; the careful Hillary freely did so. Hillary’s ‘good-taste’ carefully tailored suits and tastefully coiffed hair did not seem natural. Trump’s ‘bad-taste’ mile-long tie, orange tan, and combed-over yellow mane appeared paradoxically authentic.

Clinton was a creature of government, he often at war with it. Her misdeeds were far worse than her reputation; his reputation far worse than his misdeeds. He could be authentically gross, she inauthentically prim. And his low cunning was usually prescient, her sober assessments usually erroneous. Trump could certainly be cruel to individuals, but he was kind to the public. Clinton was kind to her particular friends, but cruel to people.

Trump not being Hillary proved to be a reassurance to half the country, in a way it might not have if another Democrat (a Joe Biden perhaps) had won the nomination. Indeed, Trump was clairvoyant about how the power of Hillary’s negatives would empower his own candidacy (and later his presidency), and how the classical fallacy of tu quoque (‘you do it too!’) would help to nullify his own shortcomings and scandals.

Finally, Hillary, as a Clinton, fed into the growing bipartisan consensus that the American presidency was not supposed to be a hereditary or dynastic office. Just as the implosion of the Jeb Bush candidacy had been an expression that two Bush presidencies were enough, so too Hillary’s failure, both in 2008 and 2016, marked a similar popular pushback against a third-term Clinton presidency. In Hillary Clinton’s case, in lieu of an agenda the candidate herself had remained the chief issue — a flawed messenger without a compensating message, and thus an unforeseen endowment to both candidate and president Trump.

This is an excerpt from The Case for Trump, out now. Another part can be read here.