What possible crime has the award-winning novelist Boualem Sansal committed that merits being locked away for three months by the Algerian police?

Listen to the Algerian government — and its cheerleaders on social media — and the answer appears to be that he is at best a stooge for the French far-right, at worst an outright traitor. Friends of the man paint another picture: a gently spoken free-thinker with the courage to speak his mind.

Sansal, who is eighty and suffers from cancer, was arrested at Algiers airport on November 16 as he got off a plane from Paris. He has been in an Algiers prison ever since, with visits to hospital for treatment. His Parisian lawyer, François Zimeray, has still not been given a visa, so the charges are unclear. What is known is that they fall under Article 87 of the Algerian penal code, which treats as terrorism any “act aimed against the security of the state, and the integrity of its territory.” Conviction carries the death penalty or a long period in jail.

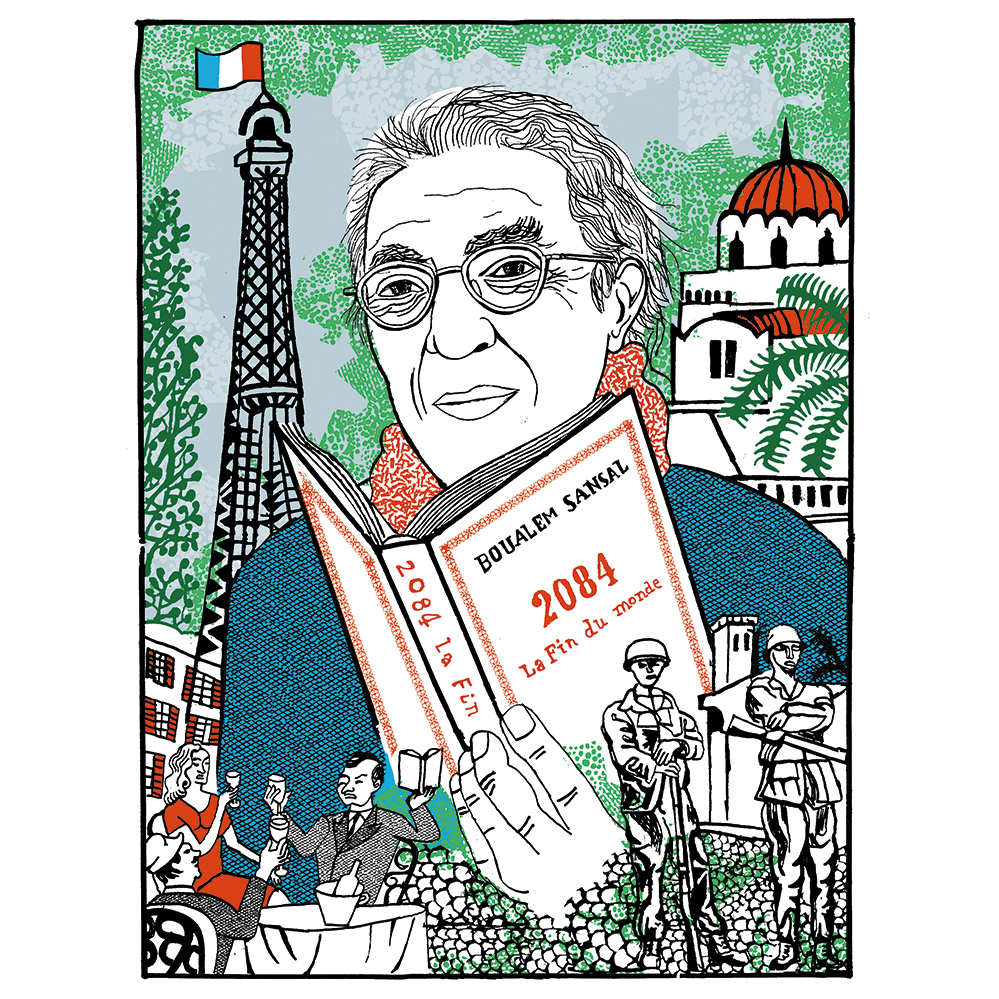

He may be little known around the world, but in France — where he has lived on and off for twenty years — Sansal has become quite a familiar figure. He produced a series of books in French, one of which — 2084: The End of the World — won the French Academy’s 2015 Grand Prix for best novel. And he appeared regularly in the media as a commentator on Algerian and French social affairs. With his gray ponytail, glasses and shabby jackets, he came across as a kind of hybrid Native-American math professor.

For his publisher Jean-François Colosimo, Sansal “is essentially a kind of beatnik. Remember he came of age in the 1960s. He’s a man who believes in human brother- hood, in a kind of love for the cosmos, and for different peoples and cultures. He really is a man of peace.”

The “man of peace” is perceived rather differently in Algiers. There — in a report on his arrest on the official news agency APS — Sansal was described as a “pseudo-intellectual venerated by the far-right,” a protégé of “Macronito-Zionist France” and a “puppet of anti-Algerian revisionism.” The country’s president, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, told a French newspaper in February that Sansal was “not an Algerian problem, but a problem for the people who created him.” Ominously he went on: “So far he has not delivered all his secrets.”

Sansal has angered the Algerian authorities because — much like his friend and fellow writer-in-exile Kamel Daoud (winner of last year’s Goncourt book prize in France) — he refuses to toe the line. His targets are both the military-backed regime and the Islamists with whom, he says, it now effectively shares power. He attacks corruption and the endless Independence War-memorializing that he believes has become the source of all legitimacy. He says society in Algeria has been anesthetized by state propaganda and Islamist cultural enforcement.

Worse, in 2012 Sansal dared to actually visit “the entity” — Israel. And in an interview shortly before his arrest with the French right-wing website Frontières, he may have overstepped the mark. Taking a long look at history, he said some unacceptable things about the Algerian-Moroccan border: about how Algeria had not existed as a country until it was created by French colonists, and how parts of western Algeria once offered allegiance to the ancient Sultanate of Morocco. That was presumably the offense “aimed at the integrity of (Algerian) territory.”

But it is not just the Algerian government that has had Sansal in their sights. In France, too, he is regarded by a large part of the political left as a contentious, not to say dangerous, figure. This is because he says things about immigration and Islamism that suit the arguments of the right. He warns, for example, that France has been naive in underestimating non-violent Islamism, which will one day become a political force in the land. Much like his fellow novelist Michel Houellebecq, he is pessimistic about the future of French civilization — to which, as an unashamed Francophile, he feels attached. His last book was a defense of the French language, which he said had been all but abandoned in France but which might yet be saved by Francophone Africa.

For the influential Paris classes, all this has made Sansal a slightly ambiguous character. It is noticeable that, despite his having received French citizenship last year, there is no high-profile campaign led by politicians to get him released, no massive poster bearing his image on Paris city hall.

One hopes that this reticence is for sound diplomatic reasons. The fact is that Sansal’s arrest is part of a wider crisis in Franco-Algerian relations — triggered by President Emmanuel Macron’s apparent tipping towards Morocco last year – and arguably a softly-softly approach is more likely to get him out. But it seems more probable that Sansal is simply the wrong kind of dissident. In Paris salons, you hear a lot of huffing about the ghastliness of the Algerian regime for taking Sansal hostage, but quite often there’s a “But let’s not forget…” at the end of it — implying that in some way he brought it on himself.

The European parliament finally passed a motion calling for his release in January, but several hard-left French MEPs either abstained or voted against on the grounds that Sansal “backed the ideas of the far-right, including the ‘great replacement’ theory.”

For Colosimo, there’s an apt comparison with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn — not least given Algeria’s historic links with the Soviet Union. “Totalitarian regimes fear literature more than anything, because they know that literature is the main way for people to understand what is their fate,” he says. “But remember Solzhenitsyn. We loved him when he was speaking against communism. But when he came out and started criticizing us for being too materialistic, then it changed and we said he was a fascist. It is the same with Sansal.

“The truth is we like our dissidents to be in our own image. When they start being dissidents against us — telling things about our countries — then we reject them.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply