Colombian president Gustavo Petro has hit out at the longstanding US ban on cocaine, in response to Donald Trump’s crackdown on the drugs trade.

“Cocaine is illegal because it is made in Latin America, not because it is worse than whiskey,” Petro argued last week, adding that “scientists have analyzed this.” He also suggested that the global cocaine industry could be “easily dismantled” if the drug was legalized worldwide.

Although I was not consulted directly by Petro, I am one of the scientists he was referring to who have analyzed the harms of various drugs. In 2010, I was the lead author of a Lancet paper which argued for the first time that alcohol was more harmful than cocaine.

Our paper, “Drug harms in the UK,” looked at twenty different drugs using different categories of harm which were weighted to reflect their importance. We found that in Britain alcohol was by far the most harmful drug, while cocaine (in powder form) was only slightly more harmful than tobacco. Since that paper, similar independent studies in Europe, Australia and New Zealand have confirmed our results.

To assess the harm that different drugs cause, our study looked at harms to the user and harms to others and society at large.

First, let’s start with the individual, and arguably the most important impact these two drugs have: the deaths they cause. There are two ways to compare the lethality of cocaine and alcohol. In its statistics, the Office for National Statistics looks at both direct deaths and chronic illness caused by these drugs (heart disease caused by cocaine use, for example, would be included in these statistics). According to this, in England and Wales there are about 8,000 deaths every year directly caused by alcohol, while around 200 deaths are caused by cocaine. If we calculate direct deaths per million users, the two drugs are about the same. Alcohol kills 260 people per million users every year, while cocaine kills 200.

The second way of looking at lethality is just to look at direct deaths caused by intoxication. Using this measure, alcohol is more than twice as lethal as cocaine.

Already then we can see that Petro is right: whiskey is either just as bad or much worse for you than cocaine.

When it comes to harms to society, things get worse for alcohol, which has a huge impact on the economy, family breakdown and injury to others.

Some would argue that the greater harms of alcohol are simply a reflection of the fact that it is legal and more people use it. But that is a somewhat specious argument. It doesn’t make sense for policymakers to ignore the overwhelming harms of one particular drug, just because it is widely used.

Others have argued that if Petro had his way and cocaine was legalized worldwide, usage would increase and societal harm would shoot up as a result. It’s not necessarily the case that cocaine usage would increase as a result of legalization, especially if it is properly restricted and regulated. But even if it did it’s not clear that cocaine would become more harmful than alcohol.

One way of finding out is to look at the harm each drug causes to the average user. In the table below, we looked at nine types of harm, each scored out of 100. For mortality, we measured direct deaths caused by intoxication.

You can see that cocaine is less harmful to the user than alcohol on most measures despite its illegal status meaning that its quality cannot be guaranteed.

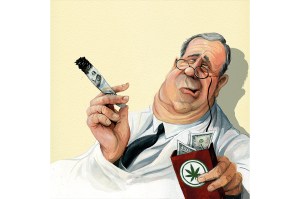

All of which supports Petro’s call for us to treat cocaine like alcohol and have a regulated market. This is already happening with other illegal drugs. The majority of Americans now have access to recreational cannabis after twenty-four states have legalized it, based largely on marijuana’s safety compared with alcohol. Allowing users to grow their own marijuana in the States has significantly reduced the income of the drug cartels in Mexico. A legal cocaine market could take even more wind out of their sails.

Legalization itself is an ill-defined term. It covers everything from an unregulated free market with no taxation or quality controls to a tightly state controlled supply. The options for cocaine have been reviewed in detail by the UK charity Transform working with Mexican experts. Their recommendation is for a carefully controlled powder cocaine market, with government taking control of the product — from growing the plant to selling the final product in a specialist shop such as a pharmacy. Crack cocaine would not be allowed.

Colombia clearly has all the natural assets needed to supply this legal trade and has good reason to do so. Donald Trump famously likes to make a deal. Perhaps Petro should agree to take back any Colombians who have a drug conviction in America, in exchange for the US supporting cocaine legalization?