Any hopes that the parliamentary recess would help resolve the great Brexit impasse have been dashed. Members of Parliament have returned from their break more entrenched in their positions.

The essential facts remain. Theresa May doesn’t have enough votes to pass the withdrawal agreement. Equally, no Brexit option from a second referendum to a customs union has demonstrated that it can command the support of the Commons either. Tory MPs lack confidence in May’s leadership but can’t agree on who should succeed her, which keeps May in place. The consequence of all this: the drift continues.

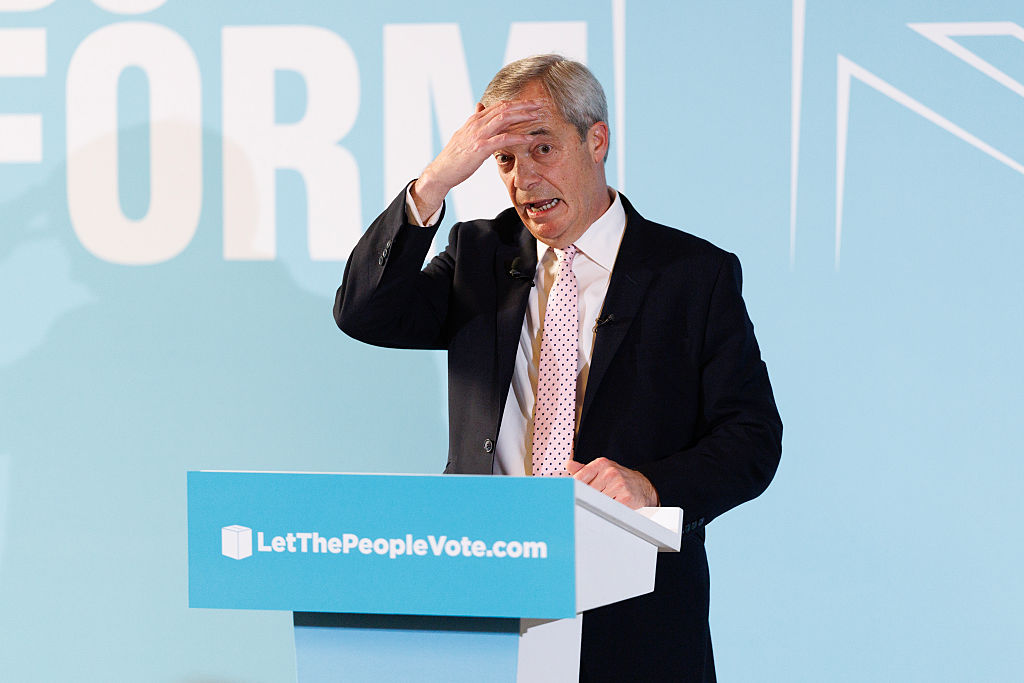

On the Tory side, the debate is fast coming down to what are MPs more scared of: May staying as Prime Minister until December or Boris Johnson taking her place? Most Tory MPs would reject both. But if May departs the scene before a Brexit deal is done, the polling indicates that the most ardent Brexiteer who goes to the membership will win.

MPs decide which two candidates go to the party in the country. There would, undoubtedly, be an operation to try and stop Johnson from making it to the members. He would need the support of a third of the parliamentary party to be sure of reaching the final two. But whoever is the hardest Brexiteer in the last round of MPs voting would have a good chance of getting that.

A rule of thumb is that the worse things are for the Tories, the better for Johnson. Tory MPs will swallow their doubts about him only if they have to. But if the Brexit party continues to eat into the Tory vote, then more and more Tory MPs will start to reach for Johnson.

The 1922 Committee of Tory MPs will be decisive. Despite its confusing name, the ’22 is, essentially, the ruling body of the Conservative parliamentary party. It is sovereign over its own decisions. So, it is within the ’22’s power to simply change the rules that mean that May cannot be challenged until December because she survived a vote of no confidence in her leadership last December..

I understand that the ’22 would be unlikely to change the rules without balloting the parliamentary party first. First, the chairman of the ’22, Sir Graham Brady, is determined to operate by consensus. He is not a show-boater but someone who understands that the Tory party needs to be put back together again. He knows that any rule change must command broad support, and not be seen as a factional device. Second, a vote on a rule change would be a proxy no confidence vote. If the rule change passed, then it would be clear that a no confidence vote would pass. This would give May a chance to leave office of her own accord with a modicum of dignity rather than being forced out.

Even a few weeks ago, a rule change seemed an unlikely proposition. At Tuesday night’s meeting of the ’22 executive, the mood was still against it. But, the more time passes with little indication of how No. 10 intends to resolve the Brexit impasse, support for finding a way to oust May will grow.

The ’22 is one of the few parts of the political system to have not had its reputation damaged by Brexit. Our MPs don’t think through the consequences of their actions. They voted overwhelmingly for both the referendum and to trigger Article 50, which began the process of leaving the EU. But they have refused to vote for the withdrawal agreement that would see Britain leave the EU.

It is absurd that the House of Commons can repeatedly reject the government’s defining piece of legislation and yet leave it in place. Until a few years ago this wouldn’t have been possible. Before the fixed term parliament act, the government could turn such a vote into a confidence matter — as John Major did with the Maastricht treaty. This meant that either the bill passed or the government fell; preventing the kind of limbo we are in today. But for the purposes of coalition management in one parliament, David Cameron and Nick Clegg junked that system.

Another problem that Brexit has revealed is the lack of experience in the House of Commons. May would not be Prime Minister today if, for instance, William Hague had decided to remain in the Commons. But there is a deeply regrettable trend now in British politics for senior politicians to quit their seats as soon as their stint in high office is done; Ken Clarke is the only former chancellor in the Commons and there are no ex-prime ministers. This lowers the level of debate and means that finding an acceptable stop-gap prime minister is much harder.

Brexit has also revealed the poor quality of the governing class, both politicians and civil servants. This country did not have a bad hand to play, but it has been comprehensively out negotiated by the EU which has known what it wanted and how to get it. The UK has not. For instance, the UK had no appreciation of the significance of the mapping exercise on cross border cooperation on the island of Ireland. It was, in the words of one well-placed figure, approached as a school Geography project rather than with an appreciation of how it would end up shaping the entire negotiations.

The executive and the civil service have demonstrated a failure to understand parliament throughout the Brexit process. The minister who argues that no one has handled parliament as badly as May since James II might be indulging in hyperbole. But there has been a failure to appreciate that a deal that could not get through parliament is pretty much worthless.

Brexit is complicated. Untangling 40-odd years of integration is not easy. But a political system that has struggled so badly needs reform. If Brexit ends up being the catalyst for this, it will leave Britain in a better position to deal with the rapid changes of the coming decades.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.