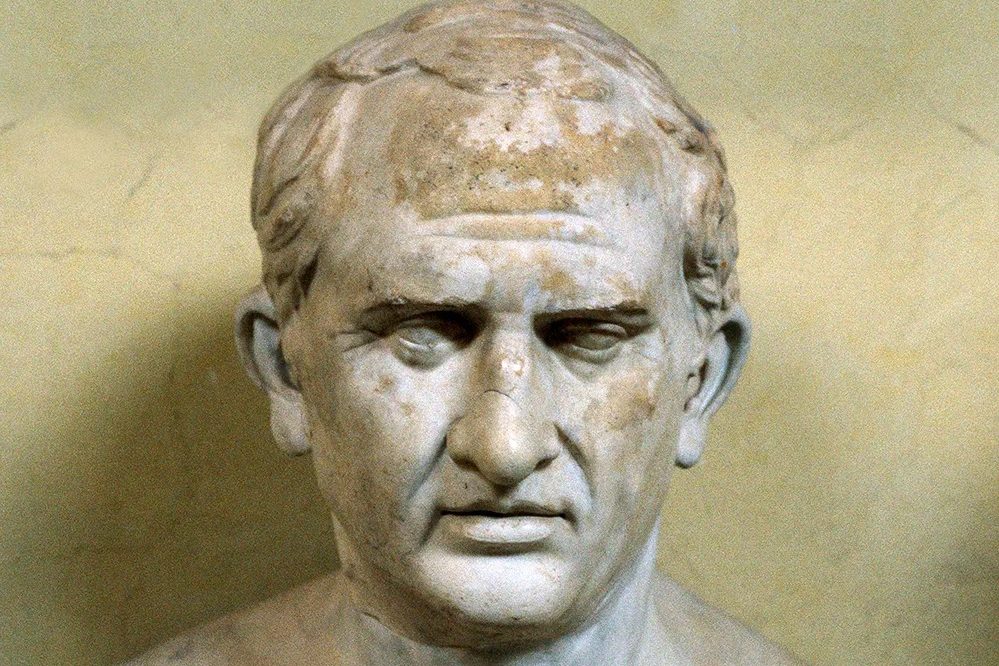

It is rare to read a book about Cicero that likens its hero to a demagogue. Rome’s prosecutor of conspiracy and corruption in the last years of the Republic is seen more commonly as a toga-draped crusader for virtue. Was he also a ranter steeped in violence, crude character-assassination, tendentious storytelling and racial stereotypes? Yes, argues Josiah Osgood, an American historian, whose book persuasively analyzes a range of Cicero’s murder, fraud and extortion cases. Other men of the time were often no better, he writes, but, echoing Michelle Obama on Donald Trump: “Fortunately for Cicero, if his opponents went low, he knew how to go even lower.”

Because Cicero wrote so much moral theory, it has been tempting to see him as he wanted to be seen. It has helped his reputation, too, that he died on the orders of the reviled Mark Antony, his hands and tongue nailed up in the forum lest he go on ranting in death. Osgood’s evidence of demagoguery includes texts used in centuries of school examinations and others less studied. The speeches against Catiline, the radical rebel, whose followers Cicero notoriously condemned to strangulation in 63 BC, stand alongside the Pro Cluentio, a case from 69 BC piled high with poisoned bodies in a plot that would take the rest of the space in this magazine to explain. In fragments of the Pro Fonteio we see a Cicero whose inner Trump more than matched his inner Obama, a man ever ready to deploy the rhetorical smear and to call all Gauls greedy, lying drunks in order to undermine a case by some Gauls against his client.

Cicero was lucky in life, becoming consul despite the handicap of his provincial family having never produced a consul before. But he was even luckier in his afterlife, because he wrote so much source material for the history of his time which has survived. A shelf of Cicero today includes more than 80 speeches, more than 20 philosophical essays and almost 40 books of letters.

Osgood is a shrewd judge of sometimes deliberately deceptive evidence. The fact that a legal speech survived is a strong indication that it originally persuaded the jury — but we often don’t know. We cannot be sure that Cicero won his famous first case, the defense of Sextus Roscius in 80 BC against a charge of patricide and the special death penalty of drowning in a sack of ritual animals. We can see how Cicero used his demagogic skills in the extortion courts by stereo-typing complainants as greedy, heavy-drinking Gauls, but we do not know the juries’ verdicts. Cicero left behind speeches that later teachers have valued wholly for their style. Who has ever cared in a Latin exam whether young Roscius went free to enjoy his father’s wealth or was drowned in a sack with a fox and a cockerel?

Cicero’s legal lessons, described by Osgood in appropriately punchy style, remain worth studying: the need for narrative theatrical skills; for the best means of challenging potentially hostile jurors; and the right level of rehearsal required for witnesses. The question cui bono? — who’s the gainer here? — popularized 50 years before Cicero’s time by a prosecutor of fallen Vestal Virgins, is still standard. Rules for relevance and admissibility of evidence were laxer in Cicero’s day. Expert witnesses were not used. The plausibility of a poisoning charge had to depend on the jurors’ own knowledge of poisons, carefully supplemented in court.

Knowledge of the law was a necessary start in Rome for anyone with political ambitions, even for such as Julius Caesar, for whom the army was the better springboard. Most voters might not be rich enough to be courtroom jurors (there was a varying but high property qualification), but all had the right to listen to the speeches from the edge of the court and remember whom they might want to be consul.

Through luck and choice of cases, Cicero won the allies who helped him to succeed. But at the center of Osgood’s account is an analysis of Cicero’s part in the political disintegration that vitiated his success. The violence of Antony, Catiline and Rome’s greatest extortionists inspired magnificent rhetoric from Cicero. But the rhetoric itself was vicious and violent.

Cicero did not use physical force well when, as consul, he had the opportunity. His decision to condemn Catiline’s allies to the state strangler was opposed by Caesar, a man with a much better instinct for when and when not to kill. Cicero should have listened. But if a gangster was on the right side, Cicero was happy, Osgood concludes, “to disregard laws when he thought them unjust or inconvenient.” The defender of Rome’s balanced form of government played a large part in its downfall. Cicero’s demagoguery helped the forces that would “ultimately kill him and destroy the Republic.”

Leave a Reply