Donald Trump has form with the smelt. In his 2016 presidential run, he complained that California’s authorities were prioritizing the endangered fish (which are native to the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta) over farmers’ irrigation needs. “Is there a drought?” he asked a private audience of farmers ahead of a rally. “No, we have plenty of water.” Environmentalists, he said, were wasting water in their efforts “to protect a certain kind of three-inch fish.”

Last week, he leveled a similar accusation against California’s governor Gavin Newsom — or, as he calls him, “Newscum” — for using the state’s water (which could have fought the LA fires) to provide the “essentially worthless” smelt with a habitat.

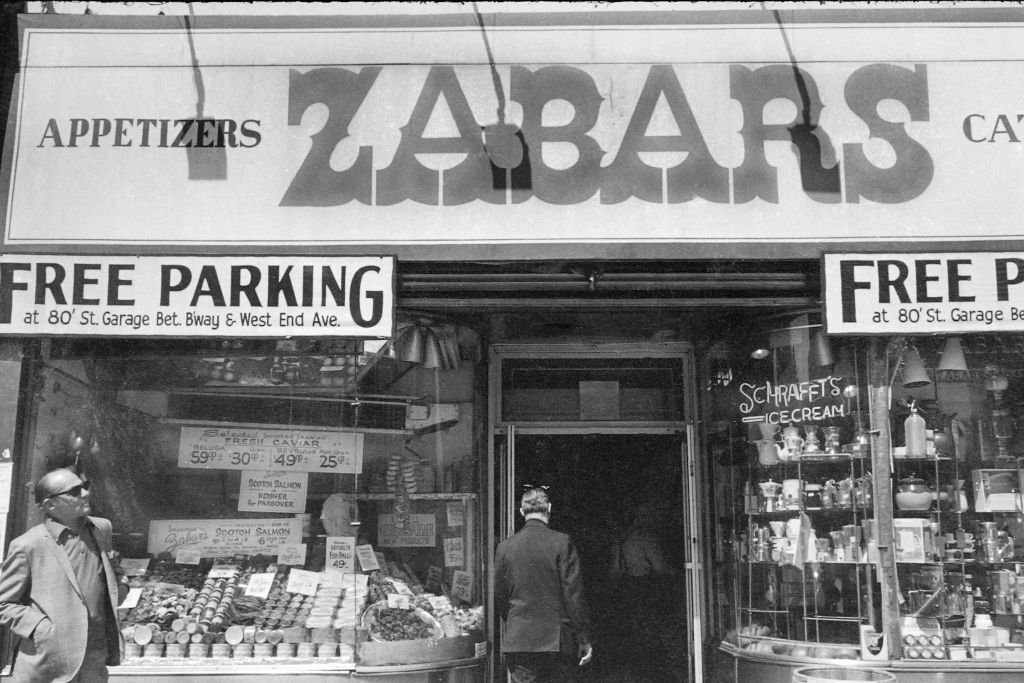

Firefighters and farmers are unhappy, but fishermen might approve: as well as catching the smelt for food, they also use it as bait to catch larger species like bass. The smelt makes things easy for fishermen by being a poor swimmer. Its slowness means that in New England and Canada people can enjoy the pastime of “smelt dipping,” which involves standing with their feet either side of a narrow stream, spotting the silver fish with a head-torch and scooping them up with a bucket or net. Larger-scale operators used to head out over frozen rivers in horse-drawn sleighs. The ice would provide a ready-made counter on which the smelt could be preserved and sold to passing buyers. If you wanted to eat them there and then, you’d dip them in flour and fry them in butter over a small stove. Smelt bones are so soft that you don’t need to remove them before eating. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were introduced to smelt on their 1806 expedition through Oregon. Lewis found them “best when cooked in Indian stile, which is by roasting a number of them together on a wooden spit.” He reported approvingly that “they are so fat they require no additional sauce.”

The name comes from the Anglo-Saxon word “smoelt,” meaning shiny, although Native Americans called it the “eulachon,” which gave rise to the fish’s modern nickname “hooligan.” They also called it the “salvation fish,” as its appearance in spring was a sign that the cold, hungry winter was over. Other names include “cucumber fish” (smells and tastes just like it) and “candlefish” — the smelt is so greasy (15 percent of its body weight being fat) that you can dry it, thread some string through it and burn it as a candle.

There are smelt festivals in places as diverse as Lithuania and the New York village of Lewiston (motto: “Lewiston never smelt so good”). Duluth, Minnesota, on the banks of Lake Superior, even has the Magic Smelt Puppet Troupe, whose annual parades include the presentation of a Smelt Queen. Spectators, should you be tempted, are encouraged to wear silver. Italians in Calabria enjoy them on Christmas Eve, while the Japanese use smelt roe in sushi. The Chinese name for the smelt translates as “the fish with many eggs,” and dim sum restaurants often serve them with the head and tails still attached. If you think that sounds challenging, best avoid South Korea — over there they eat their smelt alive.

Leave a Reply