Jordan Peterson is one of those curious figures who has, thanks to the mysterious operations of the internet, been thrust into the limelight, willingly or not. While he has become a locus of hatred for certain left-wingers, thanks to his implacable attitude toward “woke” phenomena, in reality his supposedly controversial advice amounts to little more than that young people should work hard and take responsibility for their actions. Even the bolshiest socialist couldn’t really disagree.

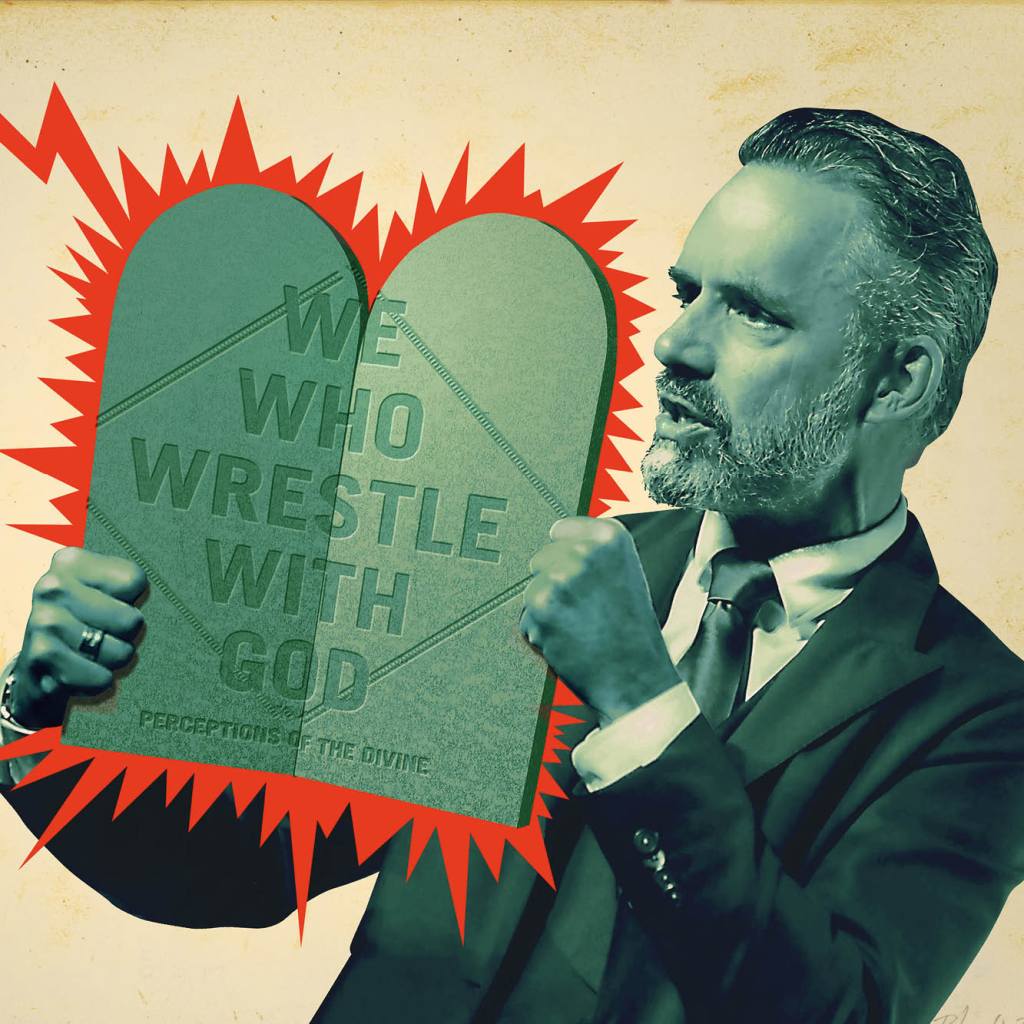

His 12 Rules for Life is a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic, and he has a large and adoring fanbase. And now, despite not being a theologian, or even, as far as I can work out, a practicing Christian, Peterson has produced We Who Wrestle with God, a tome — there is no other word for this beast — in which he expounds, exhaustingly, upon the books of Genesis, Exodus and, for reasons that escape me, but possibly because Numbers and Deuteronomy are a bit meh, Jonah. Peterson already has form with this material: his YouTube seminars on Biblical matters reach vast audiences, and so another book is the logical result.

And why not? Christianity needs a bit of a fillip. Over in the United Kingdom, the poor old Church of England has been fast withering, beset by scandals and moved by a bizarre insistence that people don’t want to be worshipping in boring old churches, and they’d much rather do it at home. A requirement for religious observance in British schools was removed many years ago, with the result that generations of children have grown up without regularly hear- ing readings from the Bible, or even the glorious language of the hymns. Culturally, whether or not you are of the faith, this is a great sadness, and it has served to unpick what was once a central thread in our national tapestry.

Christianity is certainly stronger in the United States, but here too loom the forces of materialism, individualism and secularism. Could Peterson help to bring Christianity back into focus, transmitting its core mysteries and messages to his enormous audience? The erudite thinker and novelist Francis Spufford has written beautifully and challengingly about his faith in Unapologetic, a spirited defense of Christianity; might Peterson do the same for the TikTok generation?

The answer, I’m sorry to say, is that this book is not likely to light the fire of faith in any young fan; still less will it answer any questions they might have about who we are and where we’re from. And if they come out of it with a clearer understanding of these vital Old Testament narratives, then my nephew is a baboon.

Peterson begins, like any excitable priest with a large and captive congregation, by asking what it is that the Bible stories mean for us as humans: to be created in God’s image, for the world to be flooded and Noah to be rescued, or what it’s like to find a burning bush talking to you. All well and good, and in the fine tradition of centuries of Biblical interpretation. But Peterson is a Jungian by training, not a priest, and thus he looks toward the integration of the psyche. For him, the characters in the Bible are archetypes: “the Great Mother,” “the divine Son” and so forth.

This approach has its uses, of course, as it does in literary criticism. Here, however, it tends toward repetitive interpretations that might be more suited to a counseling session. After discoursing, at some length, on the story of Lot (via Mikhail Gorbachev: don’t ask), Peterson quotes Jung, again at some length, before concluding, with a typical insouciance toward commas: “Do not look back at what you have left behind once you have learned to look forward in a better direction,” which I believe most people work out when they hear the story in Sunday school. They turn into pillars of salt! You can imagine the analyst’s brow furrowing, the fingertips touching, the kind but urgent voice, and the patient carefully noting down the bromide and tearfully promising to be a better person. Alas, this does not make for incisive Biblical exegesis.

We are also subjected to most of Peterson’s particular bugbears, and if you’ve been aware of him at all, you’ll know what they are: a repeated insistence on the biological differences between men and women, which lead inexorably to differences in behavior; a dislike of relativism, of hedonism and the creeping infantilism of culture. He hates the climate-change cult, suggesting that those who put Nature above mankind are fundamentally wrong. These opinions can be found in various forms in any newspaper column, untethered from pseudoprofound theological ramblings. There is little to argue with in many other of his assertions: he hates communism, and he also hates Nazis, which is, at least, a relief.

One of the major problems with this book is its style, if that is a word which can even be applied. Peterson’s prose reminds me of nobody’s so much as Tom Hanks’s, whose recent attempt at fiction with The Making of Another Major Motion Picture reeked of the same enthusiastic pedantry. He never uses one word when three might do, even if they mean almost exactly the same thing: when God gives Adam and Eve freedom in Eden, it is to “explore, incorporate, and otherwise use.” This effect makes him sound more like a conveyancing lawyer than a nimble scholar of thorny matters, and this reader began to be annoyed, irritated, or otherwise riled. At other times, Peterson switches his voice from dense academic to straight-talking paterfamilias, sometimes within the very same paragraph: “Bloody well beware of presuming that in the situation facing Jonah, you would have acted differently.” Well, all right then, I will, if you insist.

Parsing his sentences requires a serious amount of sustained attention (of the wrong sort): “Perhaps we need to carry with us some box, never to be opened, so that the Pandora of our inquiry does not undermine ourselves, such that we fall forever downward.” Even having read that several times, I’m still not sure what he means, since, for a start, Pandora isn’t the person you go to if you want a box to stay closed. He’s a huge fan of the phrases “to say it again” and “to say it another way,” which point to his natural forte as a speaker, but on the page simply reinforce his repetitiousness.

It can also be markedly difficult to track his line of argument: turn the page, and suddenly there’s a few paragraphs on the role of artificial intelligence or a reference to Gloucester in King Lear, to allostatic load, to the Tao Te Ching, or wham! you’re in an anecdote about his sister or something about The Simpsons. There are too many of these random swerves to note down, but I was particularly baffled by a section on Moses which transmuted into Peterson’s PhD thesis on male alcoholism. Yes, I had to read it again, which is something I would not wish on my worst enemy. Crucially, there is no index, and I wonder if, when his publishers called the Society of Indexers, they found that no one was at home.

There is, though, an even bigger fundamental problem with the book. Of mystery and of transcendence there is little. All of which makes me think that actually, and ironically, Peterson is practicing the relativism he claims to despise so much. Because if the stories in the Bible are simply exempla akin to fables, then they are not special. Why, then, should we pay them special attention? Peterson seems decidedly at odds with his own material. Spufford argues in Unapologetic that Christianity is a brotherhood joining the fieriest Westboro Baptists to the wussiest Anglican, but whether Peterson is in that brotherhood or not is unclear.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply