New Year’s marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the collective freakout known as Y2K, when overwrought tech aficionados joined forces with Luddites to warn the world of the pending apocalypse of computer infrastructure that could run the global economy but was evidently incapable of resetting to “00” in date codes. Those chiliastic projections obviously did not come to pass, which is why we can spend 2025 reflecting on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the day’s other Chicken Little situation — consternation over the transition that would, some skeptical parties feared, have catastrophic consequences for infrastructure central to the daily functioning of global markets, the final turnover of the Panama Canal.

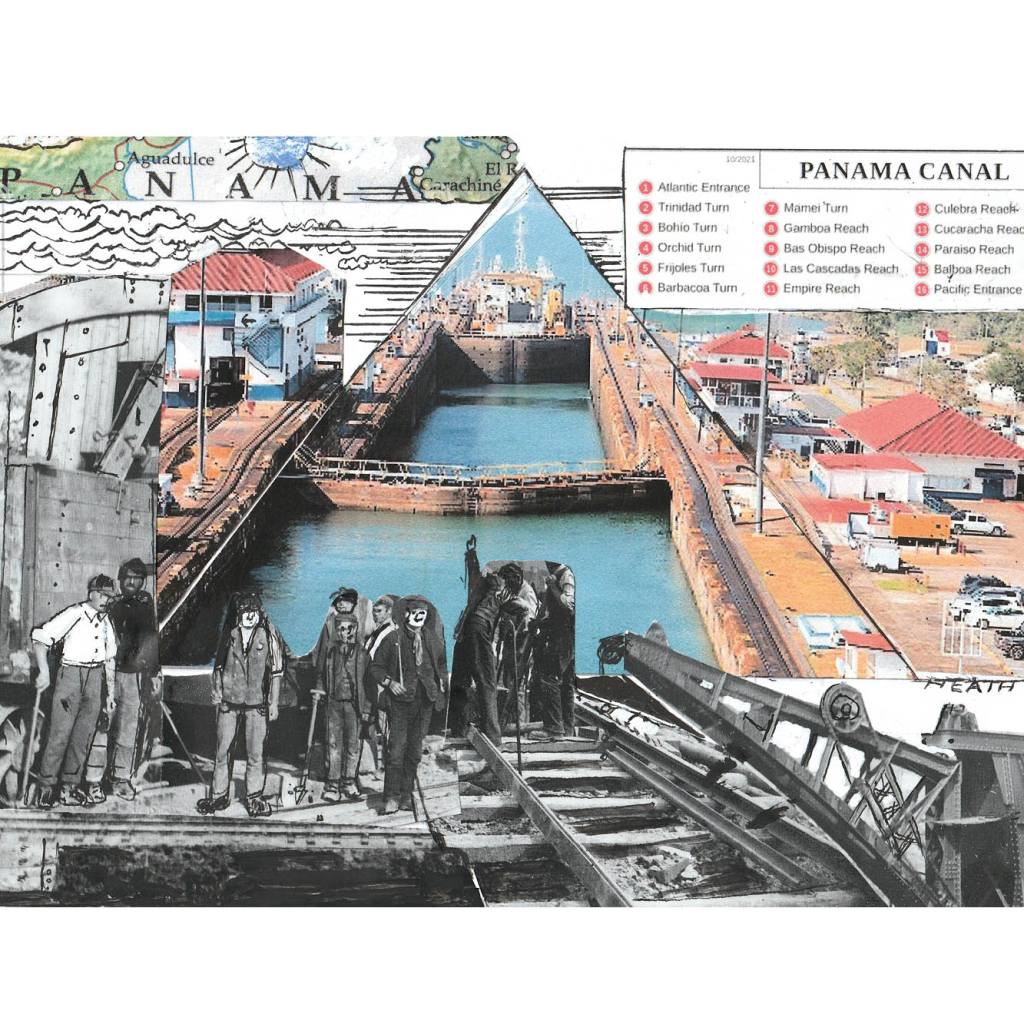

Though the canal was willingly ceded by Panamanian revolutionaries in exchange for American support for their independence from Colombia in 1903, locals always chafed under the terms of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, which granted America not only the authority to build the canal, but to administer a strip of land around the canal in perpetuity. The Panama Canal Zone, or PCZ, extended five miles on either side of the waterway, which ran fifty miles across the entire isthmus of Panama. Governed as a sovereign possession of the United States, the PCZ included not only the Panama Canal Company, responsible for the use and maintenance of the waterway (completed in 1914), but the US military facilities deemed necessary to protect it.

In comparison to the rest of Panama — which, like much of Latin America, was ruled by a small class of European-descended elites corruptly lording it over a majority of impoverished locals — the PCZ was a “red, white and blue paradise” of gringo efficiency. Thousands of American civilians and soldiers — reaching a peak of approximately 100,000 during the Korean War — enjoyed nearly a first-world level of infrastructure and services, including American-quality housing, groceries, cinemas and even golf courses. Of course, it was also subsidized by Uncle Sam to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars per year.

It was perhaps impossible that such an idyllic refuge, inhabited by American citizens called “Zonians,” would not be viewed with suspicion and resentment by Panamanians who had to cross the PCZ simply to traverse their own country, even if tales of alleged difficulties of doing so were highly embellished. Why weren’t the canal and its infrastructure theirs? Why couldn’t it be theirs?

Well, depending on what Zonian you talk to, lots of reasons. As documented in David McCullough’s 1977 National Book Award-winning The Path Between the Seas — which many Zonians label the “bible of the canal” — the Panama Canal was an incredible feat of American medical and engineering ingenuity. In the late nineteenth century, a French attempt at constructing the waterway cost 22,000 lives and almost $300 million, bankrupting thousands of French investors who gambled their retirements upon its successful completion. The project lay dormant for more than a decade until President Theodore Roosevelt’s administration saw an opportunity to foment a rebellion and create a new country, one that would exist as a US protectorate until 1939.

Two brilliant American men were most responsible for the canal: self-educated chief engineer John Frank Stevens, who conceptualized the canal’s remarkable and unprecedented lock system; and sanitation officer William C. Gorgas, who recognized that the mosquito was the preeminent threat to completing the canal. Gorgas made dramatic, wildly successful efforts to defeat malaria and yellow fever on the isthmus, and his labors are among the reasons malaria and yellow fever are no longer the killer of millions in tropical climates across the world. Given all that literal and intellectual investment, many Zonians argued, why should the United States give the canal up? Moreover, hadn’t Panama’s founding fathers agreed to America’s continued control of the PCZ?

And yet political image has a way of affecting a nation’s strategic calculus. During the Cold War, when the United States was promoting self-determination and liberal democracy, the idea of an American possession in the middle of a sovereign nation presented a bit of an obstacle to US messaging against the totalitarian Soviet Union, especially when the US presence was increasingly unpopular among the local population. When in 1964 violent riots followed a Panamanian-led student march to Balboa High School, a PCZ-administered school, and demanded a Panamanian flag be raised alongside the American flag, Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration began contemplating how to turn the canal over to the Panamanians.

It would be another Democratic president who sealed the canal’s fate: in 1977, Jimmy Carter signed two treaties with Omar Torrijos, the country’s de facto ruler, agreeing to hand the canal over to Panama. (Ironically for American messaging, Torrijos had himself seized power in a 1968 coup.) Over the next twenty years, US authorities slowly ceded various parts of the PCZ to the Panamanians, beginning with logistics, housing and medical buildings and eventually aviation and education facilities. The Panama Canal Company became the Panama Canal Commission and welcomed local Panamanians into its governance structure.

Zonian opinions over the transition were mixed, as might have been expected. Many feared the PCZ would descend into the crime-ridden dysfunction they saw in the large, densely populated ghettos not far from its borders. Others believed the Panamanians incapable of managing the complexities of one of the most important waterways in the world, through which about 40 percent of US container traffic moves every year. The Panamanian installation of a giant electric clock to mark the minutes until the final turnover at the monument of George Washington Goethals, whose role as chief engineer during the construction of the canal ensured its success, only exacerbated American annoyance.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, the US population of the PCZ dwindled, as thou- sands of frustrated Americans, even those whose families had lived and worked there for generations, packed up and headed north. Tensions with the 1980s regime of dictator Manuel Noriega — whose security forces regularly harassed and assaulted Americans — only accelerated that process. By December 1999, fewer than 1,000 of the canal employees (about 10 percent) were Americans. Though Carter arrived to participate in the final ceremonies, the US Department of State sent only junior officials, reportedly an expression of frustration over Panamanian refusal to allow the US to maintain control over Howard Air Force Base. The Panamanians in turn celebrated the greatest Christmas gift they ever received.

Today, only a few hundred Zonians remain in the former PCZ, many relatively positive on the transition. One Zonian with more than fifty years’ experience working on the canal told me the turnover was practically seamless, thanks largely to the leadership of Panama Canal administrator Alberto Alemán Zubieta. (One does hear some complaints that the Panamanian “mañana” culture has resulted in a degraded maintenance schedule for canal infrastructure and tugboats.) The canal now, directly or indirectly, accounts for more than 5 percent of Panama’s budget, and is the largest contributor to the country’s primarily service-sector economy. And — I was amazed, given my constant frustrations with living in Panama for the last nineteen months — the country was recently named the #1 destination abroad for American retirees.

As tensions grow with China, including over Taiwan, the geostrategic implications of the Panama Canal — which would enable Atlantic-based US fleets to expeditiously reach the Pacific — may be even more significant than they were when Carter signed it away during the Cold War. Senior military officials and foreign policy wonks routinely warn of the threat posed by Chinese-state owned enterprises, many of which have contracts in and around the canal. The DeConcini Reservation, a controversial amendment to the 1977 treaty, stipulates that the United States retains the right to apply military force if necessary to keep the canal open. It’s a sobering thought as Panama celebrates twenty-five years of independent control over its greatest asset.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply