As US-Iran tensions rise, America’s sway over its allies is falling. Last week, Major General Christopher Ghika, the British officer second in command of anti ISIS forces in Iraq and Syria, publicly contradicted the rationale behind American troop build-ups in the region. US Central Command was quick to rebuff Ghika, but Britain’s Ministry of Defence supported him.

Other NATO allies, too, are balking at confrontation with Iran. Spain has withdrawn a frigate from the American-led, Gulf-bound carrier group. Federica Mogherini, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs, has called for ‘maximum restraint’. If there is to be a third Gulf War, the US might find itself with fewer friends than in the last.

Is this a crisis of American leadership, or of European loyalty to the Atlantic alliance? Donald Trump has butted heads with Britain, France and Germany over Iran before, but he may need them should hostilities break out. Meanwhile, rival powers are exploiting the US-Europe split to substitute their own leadership and advance their own interests. When the United States left the ‘Iran Deal’, it left Western Europe orphaned. Europe had supported the deal, hoping to avoid war and keep Iran in the global oil market. Now, within the America-less JCPOA bloc, Russia’s growing energy influence on Europe, and China’s economic influence, threaten to eclipse Western powers’ influence on events in the region.

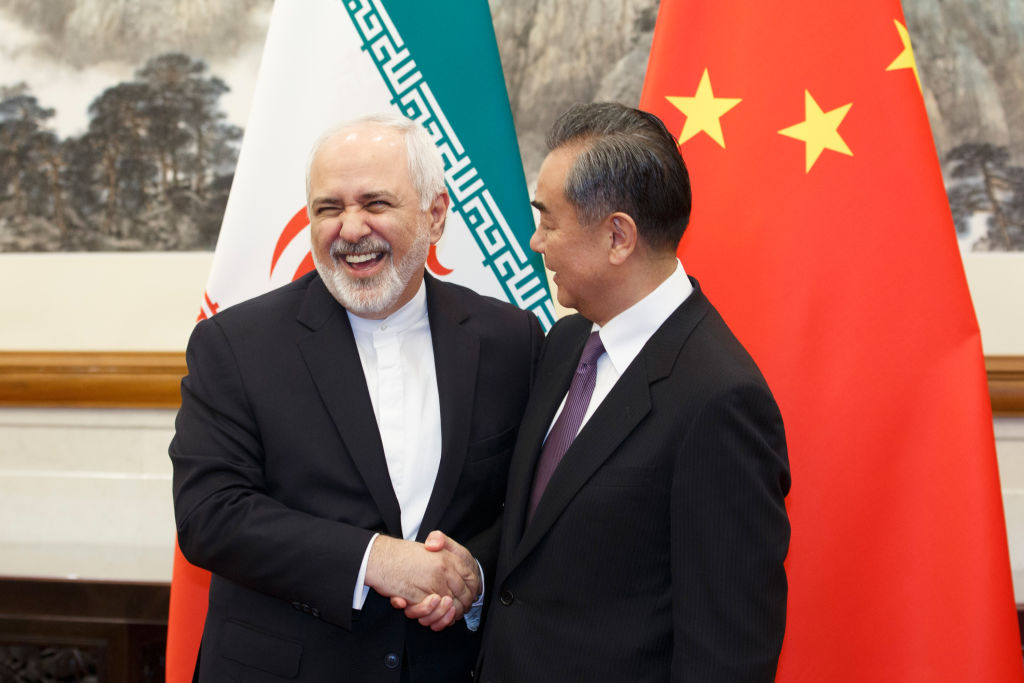

China has a ‘soft-power’ interest in reviving the Iran Deal and avoiding war in the Persian Gulf. China likes to promotes itself as a ‘responsible great power’, primarily interested in stability and economic growth. Despite internal repression, and some external subterfuge too, China wants to be seen as a steady hand in international affairs. It is uninterested in ‘regime change’, at home or abroad. Its partners can make agreements with a one-party state without worrying that, four years later, a new administration might renege. It also wants a supply of cheap oil.

Russia’s interest in Iran is rather different. The status quo does not suit Russia, which remains insecure about its great-power status. For Moscow, fomenting chaos is a cheap way of reasserting its role of preeminence in global affairs — and raising the price of oil.

Russia’s regional Middle East policy finds common cause with Iran. Both Russia and Iran wish to curb American influence in the Middle East, an easier task since the Obama-era abandonment of American hegemony in the region. The Islamic Republic’s proxies look to undermine the Sunni-Arab dominance of the region, which is backed, of course, by the United States. While Iran builds military bases in Syria, Russia has used Iranian airbases to conduct the bombing campaigns that preserved the rule of Russia’s historic client, Bashar al-Assad.

The Syrian alliance is part of a wider military partnership between Russia and Iran. Earlier this year, the two countries announced plans for joint naval exercises on the Caspian Sea, reprising the war games of 2015 and 2017. Iran is a market for Russian arms. Russia delivered the S-300 missile defense system to Iran shortly after the implementation of the JCPOA in 2016, though a later, $10 billion deal on fighter jets, stalled. If American-led sanctions on Iran are lifted, that market will expand, as the Iranian regime will have more cash.

For most countries, the primary financial importance of Iran lies in its oil. Washington’s oil embargo is an economic and political gift. Russia benefits from a constricted global energy supply, which raises the prices of its own exports. Moreover, European states had hoped that normalized relations between Iran and the West would allow themselves to substitute Russian energy for Iranian, without the complications of US-imposed sanctions. With Iran’s exports off the market, Russia will continue to exert its leverage over the European continent. The NordStream II pipeline, which continues to move forward despite American objections, may be the surest sign of European resignation over their continued dependence on Russian gas.

The American embargo is far less amenable to China, now the world’s largest importer of crude oil. Prior to the reimposition of sanctions, China spent $15 billion a day on Iranian oil. China has also invested heavily in Iranian energy supplies, and Iran is an important overland energy node in the Silk Road Economic Belt. According to the American Enterprise Institute, China invested at least $48.6 billion in purchases and contracts in Iran, the majority of which was related to energy or transportation.

Yet China has decided to comply with the new sanctions regime. Though there was a Chinese purchasing binge prior to the waiver deadline, the top state-owned oil refiners, Sinopec and the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), decided to cease importing Iranian oil, despite the hundreds of billions of dollars they have invested in Iranian oil fields.

Sinopec’s and CNPC’s moves demonstrate an unwillingness, at this point, to confront the United States. Sanctions do have an effect; both CNPC and Sinopec would worry about their access to international finance, should they run askance of American sanctions law. Rather than run that risk, it is better for now to wait and see. Having stockpiled Iranian oil, China has some breathing room to monitor developments.

The outcome of the US-Iran standoff is unclear. It is also unclear whether America’s NATO allies would support military action against Iran. Meanwhile, there are risks for both Russia and China in being too eager to capitalize on these foundering relations. But there are also great opportunities for Russia and China, both economically and politically. And should tensions continue to rise, they may not need to wait long for such opportunities to present themselves.