You’ve probably heard that we’re in a boom time for the art business, breaking sales records as fast as we can make them. This might seem strange, in a time of such political uncertainty, but look closer: the art world is a fascinating canary in our cultural/social/economic coal mine, an odd liminal zone where profound reflection on the human condition is strung up on a white wall, and traded for increasingly wild sums of money.

This ostensibly deep, meditative stuff, most often forged on dirty floors by spiritually hungry oddballs, is being gobbled up by real-estate tycoons, hedge funders and tech giants from every part of the globe, especially, lately, China and the Middle East. There is some debate about how to measure the overall size of the market, but everyone agrees that we’re somewhere in the mid 11 figures, annually ($40bn-70bn).

It pays to be rich, in the art world as everywhere else. The most recent figures available show that in 2016, galleries with less than $500,000 in revenue saw their sales decline by 7 per cent. Dealers with revenues of $500,000 to $1 million did just a little better, declining by 5 per cent. Things look different for the big guys. Dealers with business of $1 million to $10 million a 7 per cent increase in sales, while those with sales of $10 million or more grew by 2 per cent. The really big guys – those with business above $50 million – had a bumper year, with a 19 per cent rise in sales. Small and mid-size galleries are closing at alarming rates.

There’s much talk in the art world, and some substantial handwringing, about the increasing dominance of mega-galleries like Larry Gagosian, David Zwirner, Hauser & Wirth and PACE. These small corporations each operate several outposts around the wealthy world, and have annual revenues that flirt with a billion dollars. Why this increasing concentration of wealth?

Art is a global business in an increasingly globalised world, and blue chip art, sold by blue chip dealers and auction houses, has become a prime currency in the one common culture that extends from Brooklyn to Basel to Beijing: money, and the social prestige that follows upon it. There’s not a ton else that we all share when you spread the boundaries that wide, and this is reflected in the art market. The things that generate high bids generate lust and envy, and the counter-bids soar higher. It was ever thus, but not to the degree we’re seeing now. Sales based on taste, or some desire for spiritual edification, are losing out to sales based on financial speculation or raw status competition.

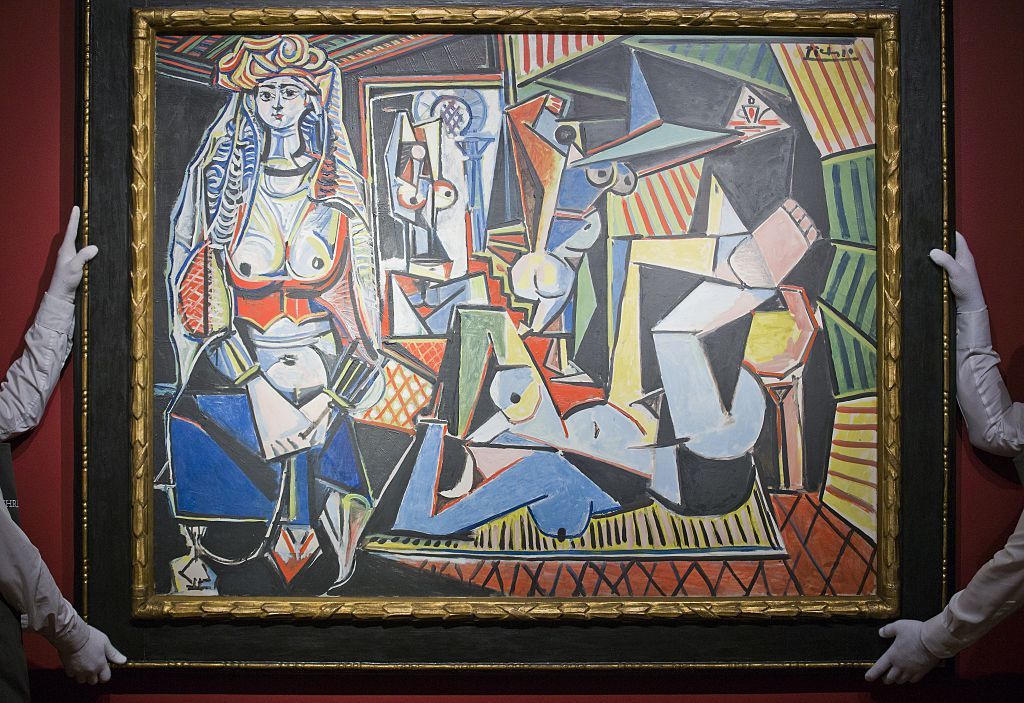

That’s why much of the art world’s growth comes from obscene, record-shattering sales like the $179 million Picasso sold in 2015, or the $500 million Da Vinci sold in 2017. The top ten biggest sales in history, all in excess of $100 million, have taken place in the past seven years. It’s great to show your friends that you have a Warhol or Basquiat, even better if you got it by outbidding all those other obscenely rich sons of bitches peacocking at Sotheby’s, or waiting in line to wine and dine with Larry Gagosian.

Life is awash with inducements to stupidity and greed. The bizarre, defiantly anti-utilitarian practice of making and enjoying art can function as a respite, a space for genuine reflection and reevaluation – as R.M. Rilke learned while staring at a broken ancient statue of Apollo, art can help us see that we must change our lives, if we want to live truly well in our short time. In our time that space is being increasingly colonised by the same venal lusts that already run so much of the wider world.

That world isn’t ending this year or next, let’s hope, so there’ll be time for correction. The new money pouring out of Asia will calm down eventually. There’s no need for garment-rending, but it is sad for us. We’re living through a moment in art history that will look at least a little gross when we, or our descendants, look back on it. A global gilded age, too busy acquiring to think about much of anything. You can fight back, for yourself and the obsessive, paint-spattered oddballs past and present, by looking – really looking – at the things they’ve produced. If you’re lucky you’ll see that there are better things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in the social registers of our hyper-competitive, status-obsessed moment.

Ian Marcus Corbin is the owner of Matter & Light Fine Art in Boston, and a doctoral candidate in philosophy at Boston College. Follow him on Twitter @ianmcorbin1