“My God, the suburbs!” John Cheever, the short-story writer who has rejoiced in the nickname “the American Chekhov,” had what can only be described as ambivalent feelings about the twentieth-century housing developments that grew up on the outskirts of major cities. He said of them that “they encircled the city’s boundaries like enemy territory and we thought of them as a loss of privacy, a cesspool of conformity, and a life of indescribable dreariness in some split-level village where the place name appeared in the New York Times only when some bored housewife blew off her head with a shotgun.”

Cheever was not wholly consistent himself. The prospect of glacial monotony did not stop the author moving to the suburbs and putting down some very firm roots both of the familial and literary kind. TIME magazine styled him “the Ovid of Ossining,” a reference to the scenic Westchester village where he lived from 1961 until his death in 1982. Admirers of Mad Men might recognize Ossining as the hometown of the ultimate suburban couple, Betty and Don Draper. This was a conscious homage; as the show’s creator Matthew Weiner has said, Cheever’s stories were a considerable influence on his writing. The show might be named for Madison Avenue, but when it comes to suburbia, “mad” is also the operative word. For a whole generation of writers trying to make sense of postwar America, the suburbs offered particularly fertile ground for “madness in the mundane” storytelling. Commingled with all that ennui, there could be sex, drink and existential messiness galore.

All this gives the lie to the fact that “suburban” has long been a code word for “boring.” As stereotypes go, rows of cookie-cutter houses, ritualistic barbecues and the hum of lawnmowers is arguably rather pleasant. I could think of worse places to be. To this day, for many the choice between a ranch-style or Dutch colonial domicile is still an encapsulation of the American dream. Yet behind the well-to-do properties and well-tended lawns lie beating hearts and harder passions. Not for nothing have filmmakers from David Lynch to Ang Lee taken suburbia’s existential mores and turned them into high — at times even disturbing — cinematic art. Yet even the most talented of directors cannot hope to compare to the literary energy with which America’s greatest writers have immortalized the suburbs.

Take Cheever’s famous — although now increasingly, and unfairly, neglected — short story “The Swimmer,” which first appeared in the New Yorker sixty years ago. It starts with one of the best opening lines of all time: “It was one of those midsummer Sundays when everyone sits around saying, “I drank too much last night.’” The backdrop is instantly recognizable. A group of moderately-heeled suburbanites sip, or slurp, gin by a poolside. The protagonist, Neddy Merrill, might lack a tennis racket but the day’s essence is one of “youth, sport, and clement weather.” Neddy gets the bright idea to “swim across the county,” figuring that by diving in and out of his neighbors’ pools, he can make it all the way back to his own home, eight miles away, all while getting progressively more intoxicated.

This might sound like a lark and a half but Cheever’s brilliance lies in his sudden, almost imperceptible turn toward the sinister. For as Neddy crashes through adjoining backyards to greet his fellow residents, we hear whisperings of his personal deficiencies: “They went broke overnight” and “he showed up drunk one Sunday and asked us to loan him five thousand dollars.” More worryingly, Neddy can’t seem to remember his fall from grace. Even his own mistress scorns him. Adultery is baked into this take on suburban mores, at least in the Sixties: the 1968 film version of the story, starring a hunky Burt Lancaster (shirtless and dripping wet), manages — unbelievably — to be more sexed-up than its source material. Let’s just say there is a lot of underwater groping.

It’s a great shame that “The Swimmer” has fallen out of fashion, most likely after being relegated to the public-school syllabus. In his narrative, Cheever depicts suburbia as both sublime and suffocating. In the end, it becomes a surreal nightmare where the night-harpies are gossip and scandal. It may be this fine writer’s greatest work, turning an apparently all-American idyll into a limitless source of dread.

Should “The Swimmer” need an accompanying summertime ditty, easy on the ear but with troubling underlying resonance, the Monkees’s hit 1967 single, “Pleasant Valley Sunday” would do nicely. For the Monkees — a made-for-television-series but remarkably accomplished rock band — suburbia was a weird “status symbol land,” and deeply suspect. Monkee Michael Nesmith once said during an interview for Blitz magazine that the song was about “a mental institution.” The joke writes itself, not least because it has the disturbing ring of truth.

Postwar writers were drawn to suburbia for creative inspiration in part because of this contradiction in terms: underneath its stagnant, conformist veneer, it housed myriad human complexities. Two other great “bards of the suburbs,” John Updike and Richard Yates, similarly drew on their own experiences living there to fuel their fiction. Updike lived in Ipswich, Massachusetts, from the 1960s and set much of his fiction in New England. Yates based his semi-autobiographical Revolutionary Road (1961) — an unflinching portrayal of a couple’s unraveling hopes in the face of stifling mid-century conformity — on the troubled year he and his first wife spent living in Redding, Connecticut. In the novel, Frank Wheeler, father and husband, is a smarmy intellectual trapped working as a salesman for his father’s company, bored out of his brain and yet somehow in thrall to the “needle of the office clock.” The family intends to flee to Paris to escape from the rat race: matters do not proceed as planned.

If Cheever is the poet of the suburbs, and Yates the moralist, Updike is an anthropologist. He is also the most optimistic. Indeed, Updike has more fun in general with suburbia’s propensity to moral dubiousness. He took an almost perverse joy in facing up to a fact most choose to ignore: Suburbia’s superficial respectability made sexual deviancy more likely rather than less. Human desires, of course, remain the same whether they’re tucked safely behind a white picket fence or cohabiting in a high rise. As the protagonist of Updike’s Rabbit, Run tetralogy, Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, realizes, there is “one world: everybody fucks everybody.” Rabbit, a former highschool basketball star who finds himself stuck as a salesman for a kitchen gadget called the Magipeeler, cheats on his pregnant wife to escape the suburban doom loop. He eventually, as the title suggests, runs away entirely.

For Updike, extramarital affairs were part and parcel of suburban existence. Not only was he a serial cheater in real life, his novels have become synonymous with domestic debauchery. When he graced the cover of TIME magazine in 1968, it was under the headline “The Adulterous Society.” Updike knew the old adage “sex sells” by heart; his novel, Couples, was published that year to much critical acclaim. Its upfront sensuality and candid portrayal of how the pill’s advent shook up traditional notions of marriage won it high praise. The novel is an intriguing study in realism, but one comes away from reading it with a sordid aftertaste, remembering little else but the heaps and heaps of polyamorous swinging and copulation. David Foster Wallace, approvingly quoting a friend, went for the jugular (and nether regions?) when he dismissed Updike as “just a penis with a thesaurus.”

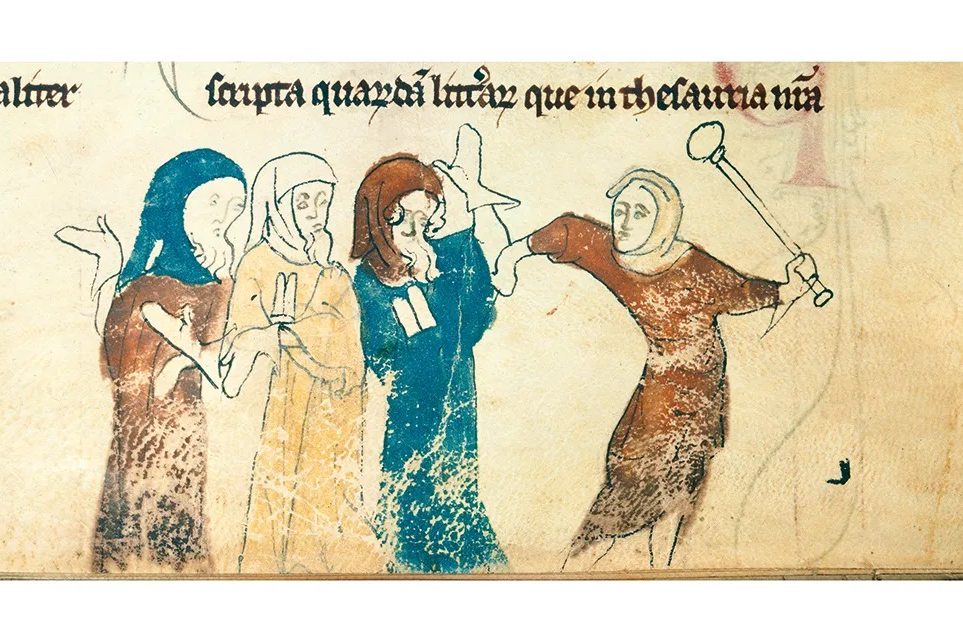

Far more fun is Updike’s Witches of Eastwick, published forty years ago this spring. In place of the depressing sexual realism of Couples, we get magic realism, some light relief for suburban suffering. In Eastwick, “wickedness [is] like food: once you got started it was hard to stop; the gut expanded to take in more and more.” Updike’s strand of wickedness is a jolly one, and the mischief makes it his funniest and most light-hearted work. It was later memorably filmed with Jack Nicholson — who else? — as the devilish, in both senses, outsider coming into suburbia and upturning bored housewives’ lives. Perhaps Updike’s satirical point is that, in the humdrum sterility of the suburbs, the appearance of Satan is a consummation devoutly to be wished.

Would that such treats came to its observers. Much of the despair one finds in the suburban fiction of Updike, Cheever and Yates leaked out from their own frustrated lives. Cheever was a repressed homosexual who turned to drink. Yates was bipolar and alcoholic. Updike was doomed to a level of priapism that might sound enviable but was also an exhaustingly time-consuming addiction. (Was it he or another writer who would say, after the umpteenth orgasm of the day, “there goes another novel”?) For them all, suburbia was something of a Faustian bargain: one must accept that the price for this middle-class Shangri-la is an accompanying middle-class malaise.

So suburbia’s reputation as a quaint, leafy, relatively “nice” place to ride out one’s life has yet to be redeemed. Perhaps it does not deserve to be. As it stands, its place as a literary locus in the American canon is a fraught one. Pleasant Valley, Pleasantville, whatever its place-holder name, in the worlds of these three bards, it is riddled with vice and viciousness alike, of a kind to make even Don Draper blush. Perhaps suburbia isn’t so pleasant after all.

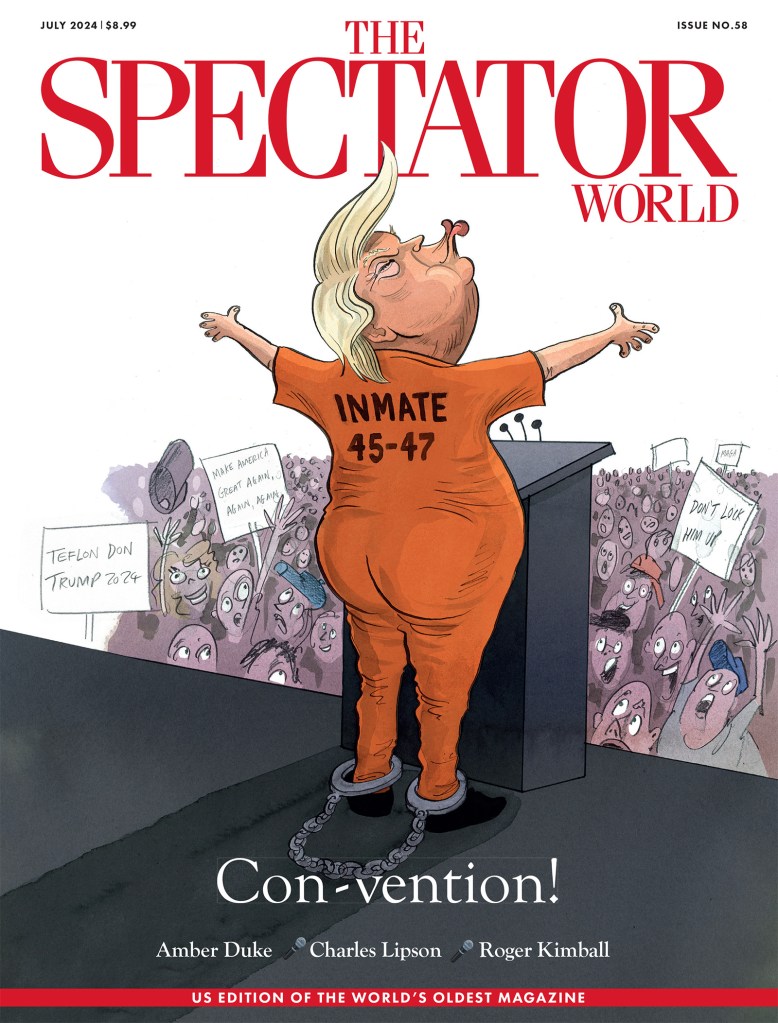

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.