Zimbabwe

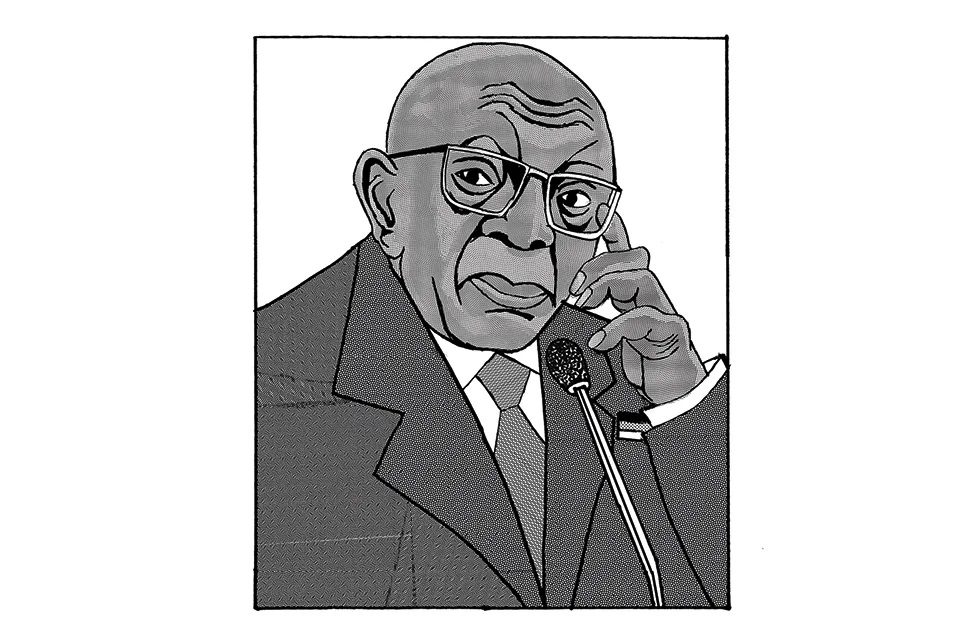

For a decade to 1973, Jacob Zuma — or JZ as he is known — was an inmate of Robben Island, the infamous prison built on a 1,300-acre slab of rock four miles off the South African coast. A fellow inmate was Nelson Mandela, also inside for treason. Both went on to become presidents of South Africa; but whereas Mandela had the Robben Island prison shut down and turned into a national monument, JZ, who has once again set his sights on high office, now wants it re-opened.

In 2018 Zuma was removed from office by the ruling African National Congress (ANC), accused of theft and embezzlement. It’s bizarre that he has now made a return to politics in the run-up to the May presidential election, but so far his brand of patriotic populism has once more proved appealing.

The new inmates of Robben Island, in Zuma’s vision of the future, will be mothers and babies. In 2023, an estimated 80,000 underage girls, mostly black, became pregnant. Many dropped out of school as a result, so Zuma’s plan is to build a university on the island where these young girls can complete their studies. He has not explained how so many people, along with teachers and other staff, can be accommodated on such a small piece of land.

His other big idea for education is to bring back caning for errant schoolchildren, especially those who play truant. Though corporal punishment has been banned since 1997, Zuma isn’t wrong to think it a popular proposal. In 2022 a survey by the Afrobarometer, a respected polling firm, showed that a majority of South Africans agreed that it’s OK for naughty kids to get a whack.

Zuma, who had little schooling, appeals to the masses as someone who has walked in their shoes

If you remember the original British TV series House of Cards, with the fictional prime minister Francis Urquhart, you’ll recall his shock move to bring back the national service. Well, JZ wants that too. “There will be no gap year,” he explained. “Going to a military camp will teach [young men] to be responsible citizens. It will also give them discipline and important life lessons.” Some say that in a country with the world’s third-highest murder rate, teaching youngsters to use machine guns might not be the best idea.

In 1975, having been released from Robben Island, Zuma headed the intelligence branch of the ANC’s military wing, uMkhonto we Sizwe or MK, “Spear of the Nation.” In December last year, he revived MK, this time not as a guerrilla movement but as a political party. The ANC has gone to court claiming they own the brand, but the ANC is not on the front foot. A few weeks ago a national poll showed that its support has dipped to 39 percent. The opposition Democratic Alliance is just eleven points behind, and from nowhere Zuma’s MK has picked up 13 percent, making it the third-largest party. His bid for power isn’t even technically legal: the constitution allows a president to serve no more than two terms, and Zuma has done that, from 2009 to 2018. But even so, his party has fielded him as its candidate, and threatened violence if his name does not appear on the ballot.

If it seems odd for people to support someone facing multiple charges for embezzlement, and who’s already served two presidential terms, remember that South Africa remains a deeply conservative society. Black men are expected to pay a bride price to the father of their fiancée, and women do most of the child-raising. It’s not unusual for youngsters to stand when grandparents enter the room, and men and women do not talk about sex in polite society. In Afrikaans — among the most widely spoken languages across all races — it would be unthinkable to address an older person by name; rather, they are respectfully known as “Uncle” or “Auntie.”

The ruling party is full of lawyers and intellectuals but Zuma, who had little schooling, appeals to the masses as someone who has walked in their shoes: a cattle-herder from a poor Zulu family, one of the millions struggling to get by while the black and white elite turn a deaf ear to their plight.

A quarter of all South Africans live in the tiny Gauteng province (1.5 percent of the country’s total land area) that includes the country’s largest city, Johannesburg, and the capital, Pretoria. Zuma proposes a system of decentralization with incentives for factories to set up in towns and villages so people can work close to home.

Some portray Zuma as an uneducated yob, but he is far more complex than that. On Robben Island inmates would unburden themselves to him, knowing he would never break a confidence. To while away the time, he introduced the inmates and some of the guards to chess, a game he still enjoys.

Yes, he has a history of corruption, but in South Africa that’s par for the course. In 2020, $580,000 in banknotes was found hidden in a sofa on president Cyril Ramaphosa’s farm, 120 miles north of Johannesburg. As they had done with Zuma, the ANC used its numbers in parliament to stop debate on the matter. And when its own list of candidates was leaked recently, it read like a Who’s Who of those named in the seemingly endless scandals.

South Africa has been a republic since 1961, yet within its borders several kingdoms remain in play — none more powerful than that of the Zulus, the warrior nation accounting for a fifth of the population, who in 1879 defeated the might of the British Empire at Isandlwana. In the past three years, the Zulu king Goodwill Zwelithini and his prime minister Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi — legends on the political landscape for more than half a century — both died of old age, leaving a void in the heart of the tribe. Zuma is ready to fill that void. He once drew the Zulu vote to the ANC, but now it could form the backbone of his new MK.

After more than 400 years of European influence, during which various parts of the country have been ruled by France, Britain and the Netherlands, and used by Portugal and Germany as a supply base, South Africa has a complex legal system known as Roman Dutch Law. JZ wants to replace this with what he calls “African law.” Across much of the continent, homosexual acts are banned and Uganda has proposed the death penalty for them. South Africa legalized same-sex marriage in 2006. At the time Zuma described the idea as “a disgrace to the nation and to God,” and in February a rally of MK supporters cheered when he asked: “Who made the law that a man can date another man?” The question was rhetorical but the answer is that Nelson Mandela made the law and it was approved by the ANC.

Human rights advocate Peter Tatchell has accused Zuma of betraying Mandela’s legacy of tolerance by pushing a populist agenda. “These illiberal social policies will do nothing to address people’s prime concerns — unemployment, poor housing and the cost of living crisis,” he said, adding that any steps to criminalize homosexuality would contravene the South African constitution.

But the West’s preoccupation with being socially liberal does not resonate in the poorer parts of South Africa. There’s a disconnect between the upper quintile who dominate the media, politics, business and government, and the millions who live in one-room shacks and go to bed hungry. The media focus on stories about climate change and what pronouns we should use. They frequently cite Donald Trump as a threat to democracy and worry about the plight of Gazan refugees, without a thought for the thousands of people driven from their homes by Islamic militants in northern Mozambique, just a two-hour flight from Johannesburg.

Zuma is a wealthy man, and as president he did little to improve the lot of the majority. But in a country with eleven official languages, his message comes through clearly to those who say their pain has gone too long unrecognized in a country characterized by poverty, record levels of unemployment and the dream of a new South Africa that never came to pass.

Zuma is ready for one last game of chess and, come May, it looks as if this could be checkmate for the ANC.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.