During the negotiations between the UK Foreign Office and the Chinese government that led to the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China, I was engaged in the fruitless search for oil in the South China and Yellow Seas, in partnership with the China National Offshore Oil Corporation, or CNOOC (“Snook”). These arrangements were the first to be concluded with western companies since the Cultural Revolution. They were conducted with a chilly civility in Beijing — then still a spartan city to say the least, with only two hotels available to western visitors.

We were installed in the north of the city in a hotel designed allegedly by I.M. Pei, about an hour’s drive from the CNOOC offices. The day always concluded with a “banquet,” an oxymoron if ever there was one, where we chewed our way through heaven knows what washed down with some evil rice wine, or Tsingtao beer if we were lucky. The events commenced at 6 p.m. and terminated on the dot of eight, when we were liberated to return to the fragrant hills. I had brought a box of cigars and a ration of novels by P.G. Wodehouse, so I was impervious to the loneliness of those long nights. Our party included Geoffrey Stockwell, previously the chairman of the Iraq Petroleum Company, and a benign fellow traveler, Alan Johnson, our chief geologist. Witty and long-suffering, he could extract humor from almost anything. Also with us was a veteran Palestinian geologist, Sami Nasr, a resident of Australia, who had married a very Irish matron at the Kirkuk Oilfield Hospital. Sami, at our first breakfast, insisted on ordering a six-minute boiled egg. Inevitably, six solid eggs eventually found their way to his plate.

We had raised some money for the project in Hong Kong through a special purpose vehicle, as a result of which the Hong Kong Bank (now HSBC) owned 30 percent of Cluff Oil. I had been surprised at the warmth of our welcome in Beijing and the general consideration given to our welfare, the reason for which was revealed at our first meeting with CNOOC where an enormous blackboard displayed our corporate structure in chalk. This revealed CNOOC’s misunderstanding, not that the Hong Kong Bank owned 30 percent of Cluff Oil, but rather that Cluff Oil owned 30 percent of the Hong Kong Bank! I did not disabuse them of this error. And I recall that Michael Sandberg, the genial chairman of the bank at the time, was much amused when I relayed to him the involuntary subterfuge which largely led to us securing the licenses in the South China and Yellow Seas.

We made frequent trips via Hong Kong to Beijing and to Shanghai, where we eventually opened an office, and we became very fond of our CNOOC opposite numbers. I once had a memorable night in the Sassoon Villa in Shanghai. I lay awake as I could hear the railway engines shunting and hooting in the distant marshalling yards, somehow an eerie sound resonant of pre-war China. During the night it was so cold that the water in the glass by my bed froze solid. Eventually I struggled out of bed to shave in the porcelain washbasin, made in Staffordshire in the 1920s, which suddenly, shrinking from the cold perhaps, detached itself from the wall and crashed to the ground.

During these expeditions to and from Beijing and Shanghai over a number of years, the scene was set for the negotiations which Mrs. Thatcher ordained should end the looming uncertainty regarding the lease on the new territories. Since the lease was about to expire, it was impossible for the banking system to grant new mortgages. It was largely under pressure from the banks that Lord MacLehose, the then-governor of Hong Kong, had raised the issue with the President of China on a routine visit. Their discussion precipitated the talks which led to the 1997 handover. Spending as much time in Hong Kong as I did — indeed I got married there in 1993 — I came inevitably to discuss the “handover” issue with highly intelligent Hong Kong Chinese professional and commercial friends. That they had not been consulted about any aspect of their future clearly rankled, and rightly so, since their destiny was about to be determined without any input from them. No doubt Mrs. Thatcher wanted a problem solved and instructed the Foreign Office to get on with it. Again and again I was advised by my Chinese friends that no treaty would be worth the paper it was written on. And how right they were!

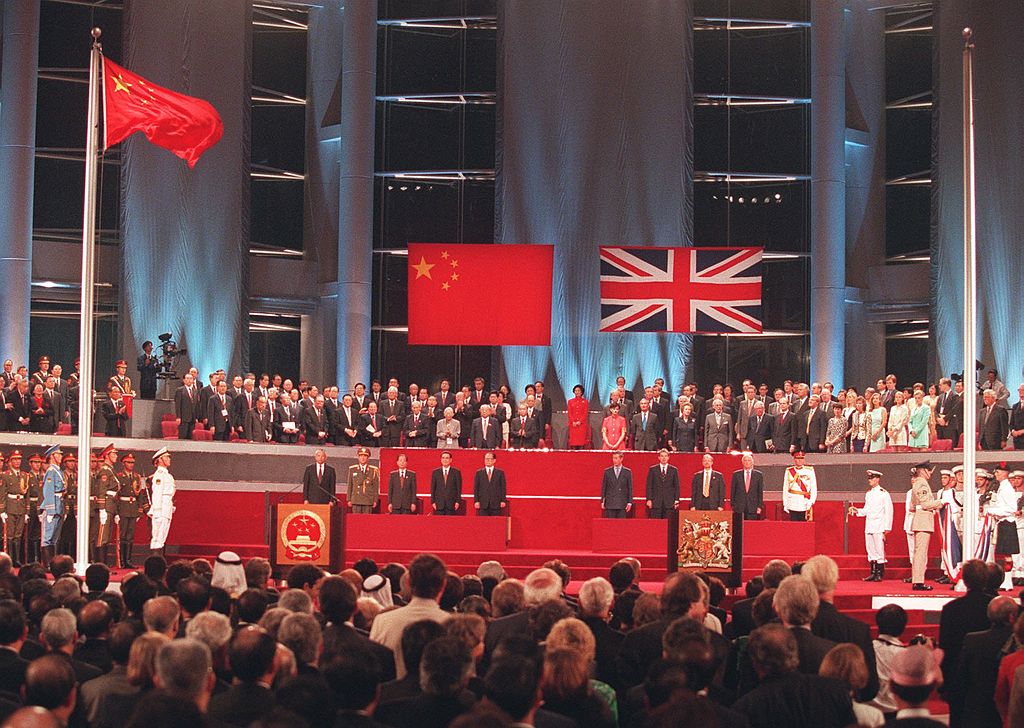

Was there an alternative? At the time, China was chronically short of foreign exchange. My friends were all of the view that an extension of the lease for fifty years at a significant cost to Hong Kong would have been welcome to China, provided it was dressed up as being “the Chinese idea.” The two flags of the People’s Republic and the United Kingdom could have flown side by side, and harmony continued, instead of the ill-tempered handover followed by successive abrogations of the terms of the “one country, two systems” arrangement. To me, it seems nothing less than incredible that we were so discourteous, and so stupid, as not to consult the people of Hong Kong about their future.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.